A few hours after pronouncing a ruling on one of Samsung's numerous lawsuits against Apple, the Mannheim Regional Court held a hearing on one of Apple's many infringement lawsuits against Samsung.

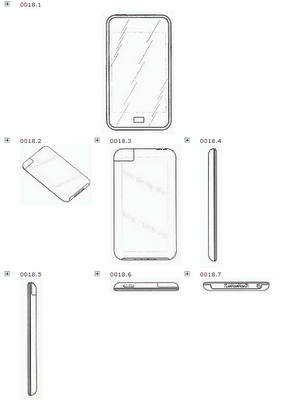

Today's hearing relate to a Gebrauchsmuster ("utility model"), which is an intellectual property right that could be vaguely described as a fast-track patent that comes with various limitations. Companies are free to file for patents and utility models on the same invention (or on closely related inventions), and that's what Apple did with its ever-more-famous slide-to-unlock image invention. Stemming from the same original application, two manifestations of this intellectual property right exist in parallel in the German market: a patent (EP1964022 as well as a German utility model (DE212006000081).

By now I have watched three German court hearings related to the slide-to-unlock invention. In mid-December, the Mannheim court heard Apple's slide-to-unlock patent lawsuit against Samsung. In its original complaint, Apple asserted both the patent and the utility model, but the court deemed it appropriate to sever the utility model-related claims from the patent case given the complexity and unique characteristics of both sets of issues. The slide-to-unlock patent is also being asserted against Motorola in a Munich-based court. At the Munich hearing, I believe some reference to the utility model was made, but it's unclear whether it was part of the same case or also at issue in a separate proceeding there -- or whether it was only mentioned in connection with validity issues common to both. Unlike in U.S. court proceedings, complaints and similar documents aren't publicly available over here.

Two fundamental differences between utility models and patents played a key role at today's hearing:

Since utility models are registered without an examination process comparable to the examination of patent applications, there is no presumption of validity. It's a prerequisite for an infringement ruling that the court concludes that the claimed invention was novel and non-obvious at the time of registration. In this case, the court believes a potential decision on validity or invalidity is too close to call, at least before today's oral argument took place. As a result, the court may opt to stay this case pending the resolution (at least at the first instance) of a parallel invalidation proceeding before the Munich-based Federal Patent Court. As courts do in all cases in which a stay is a possibility, Judge Andreas Voss pointed to the benefits of a more efficient use of court resources as well as the avoidance of inconsistent rulings.

The strongest counterargument against a stay is that justice delayed is justice denied. In this case, that argument is particularly strong since Apple registered the asserted utility model in 2006. The maximum term of validity of utility models is 10 years (while patents are valid for up to 20 years). After the resolution of all of the pending issues, the asserted utility model would be on the verge of expiration and, therefore, commercially devalued.

Apple's counsel said that it wasn't possible to assert this utility model against Samsung's products much earlier because they are relatively new. Samsung's counsel replied that some of them are two to three years old. At least in some cases, I have no doubt that Apple's couldn't-sue-sooner claim is correct. The best example is the Galaxy Nexus, with respect to which Apple today filed (with yesterday's date) supplemental infringement contentions.

I haven't previously seen the Galaxy Nexus named explicitly as an accused product in any Apple lawsuit. It doesn't even appear to be targeted by a new design rights lawsuit brought by Apple in Düsseldorf this month. The Galaxy Nexus didn't show up on the list of accused products that Germany's most-read IT news site obtained from a spokesman for the Düsseldorf court. The Galaxy Nexus is an "Android lead device" (for the latest Android version, dubbed Ice Cream Sandwich), which makes it particularly key to Google's strategy.

On March 16, 2012, the Mannheim Regional Court will pronounce some kind of a decision, which could be a ruling (if the court considers the broader claims of that utility model valid, infringement appears to be beyond reasonable doubt), a stay (pending the aforementioned parallel nullity proceedings), or a decision to appoint an independent expert in order to help the judges assess whether the claimed utility model is obvious or non-obvious over certain prior art combinations. Apple would obviously prefer for the court to reach that ocnclusion without further delay, but as a second-best solution it could live with the appointment of a court expert. It just hopes to avoid a stay.

In connection with the disputed validity of that utility, Samsung emphasizes an obscure Swedish device that previously persuaded a Dutch judge to doubt the validity of Apple's slide-to-unlock patent. In the utility model case, the Mannheim Regional Court could decide in Apple's favor without even having to go into technical details on the Neonode device. In order for the widely-unknown device to be eligible as prior art in a utility model case, the standard for availability is higher than for patents. It's not clear whether Samsung can prove that this device counts as prior art in this context.

Rather than going into further detail on the issues surrounding the slide-to-unlock invention, I'll just wait for the court order that will come down on March 16.

In closing I'll tell an anecdote from the beginning of today's hearing. Samsung's counsel moved to stay the case until Apple posts a bond covering its potential liability for court fees and Samsung's legal fees according to the German "loser pays" principle (which in cases like this awards amounts that are typically much less than what a defendant like Samsung actually spends). In my estimate, that amount is on the order of a few hundred thousand euros. That's not a lot of money for these two companies. Such a bond is formally necessary because the plaintiff in this case, Apple Inc., is domiciled outside of the European Union. Apple's counsel objected to this untimely motion, and after a recess of about 15 minutes, the court agreed that it would be sufficient for Apple to post the required bond at a later time. If Samsung's motion had succeeded, it would probably have delayed the case by only a few weeks -- over an amount that no reasonable creditor would have to be worried about if Apple, a company that has far greater cash reserves than anyone else in the industry.

If you'd like to be updated on the smartphone patent disputes and other intellectual property matters I cover, please subscribe to my RSS feed (in the right-hand column) and/or follow me on Twitter @FOSSpatents and Google+.

Share with other professionals via LinkedIn: