Sign In to Your Account

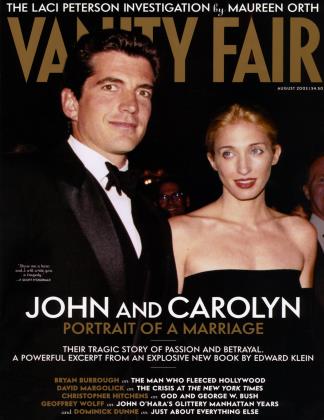

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Road to Samarra

Ne'er-do-well son of one of Pottsville, Pennsylvania's most prominent families, John O'Hara lit out in 1928 for New York, where he blew through six journalism jobs in three years while storming the editorial walls of Harold Ross's New Yorker and consuming herculean quantities of alcohol with such literary miscreants as Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In an excerpt from his forthcoming O'Hara biography, GEOFFREY WOLFF recounts the epic bender—speakeasies and fistfights, debt and depression, marriage and divorce—that somehow led to a Great American Novel: Appointment in Samarra

GEOFFREY WOLFF

In the spring of 1935, less than a year after the publication of John O'Hara's novel Appointment in Samarra scandalized and titillated the citizens of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, with its account of a prominent young man's shattering fall from social favor, the author wrote a letter to Walter S. Farquhar, star sports editor of the Pottsville Journal, from which O'Hara had been fired as a reporter. A mentor and friend, Farquhar had written asking for help getting a job with a magazine or book publisher in New York; O'Hara couldn't promise a job, but he gave plenty of free advice:

If you write a movie plot I'll get you dough for it, a novel I'll help you sell it, a poem I'll help you sell it, I'll give you a send-in that will count with any publisher in New York.... The same with the better magazines. I'm known to them, and I will help you sell a good article or story to almost any mag you mention, if it's one of the better magazines_If you're going to get out of that God awful town, for God's sake write something that will make you get out of it. Write something that automatically will sever your connection with the town, that will help you get rid of the bitterness you must have stored up against all those patronizing cheap bastards in that dry-fucked excrescence on Sharp Mountain.

What we may read into this relationship between town— which O'Hara renamed Gibbsville in his book—and novelist is hardly a failure of communication, but how had it soured so? After all, this was the altar-boy eldest son of one of the most esteemed families in a region stingy about bestowing its esteem. Of course, the words "writer" and "alien" go together as comfortably as "privileged" and "insider." John O'Hara, by virtue of his standing as a doctor's son, was a privileged insider as well as a self-exiled outcast. The imaginative writer doesn't flinch from the objectionable, courts outsider status, makes trouble, relishes gossip and scandal. In O'Hara's long story "Ninety Minutes Away" (1963), the police sergeant of such a town as Pottsville disparages such a reporter as its author— "poking your nose in where it doesn't belong"—for being "an againster."

For those with a commitment to serenity, to closing the doors behind them and drawing the curtains and keeping from children the messy sights of birth and death, it must seem perverse: disturbing the peace, showing off, telling secrets, wanting more than what's been offered. And it is perverse reflexively to say, "No way," "Fuck you," "Gimme." But O'Hara had an imaginative writer's natural reflexes right from the start: he understood very well that if fiction is about any general impulse, it is about denial. Someone wants something that someone else— many someones, the great "They"—will not give. Club membership, a kind word, love, a Nobel Prize, piles of money, the presidency, a clean bill of health, a nice review, a bicycle for Christmas, sexual intimacy, a starting position on the football team, an entry in Who's Who or in the Social Register ... There are as many things to be denied as there are to be desired, and people to want and withhold them. If writers differ intrinsically from other people, their difference is defined by a vocational obligation to be dissatisfied. Good fiction comes of friction, so why should Pottsville, Pennsylvania, as close in its business of coal mining as human beings can get to the commerce and sociology of an ant colony, honor an enemy of industry, subordination, and order?

Excerpted from The Art of Burning Bridges: A Life of John O'Hara, by Geoffrey Wolff, to be published in August by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.; © 2003 by the author.

Hemingway wrote that O'Hara "knows exactly what be is writing about and has written it marvelously well"

The society John O'Hara was bom into on January 31, 1905, was superficially stable and thriving, and the economy would mature and flourish with him, peaking just before he left the region—more or less for good—in the late 1920s. The eldest of eight children in an Irish Catholic household, he was always a disappointment to his father. After John failed to make the grade at two prep schools, Dr. O'Hara decided to give him a final chance to redeem himself as a student. Pulling strings at Niagara University, which he had attended, Dr. O'Hara got his son admitted to its prep school in the fall of 1923.

Almost 40 years later, writing to the New York city planner Robert Moses, O'Hara summarized his experience: "I had a good year there," even if "I felt I was about 55 years older than everyone else in the school." In fact, drink undid O'Hara at Niagara Prep, which was in the control of the Vincentian Fathers, and his sorry end was a sad comedy of self-destruction. Having taken his entrance exams for Yale, and having been named class poet and valedictorian, he prepared to deliver his 1924 graduation remarks on the subject of "Damnation and Procrastination." Dr. O'Hara and his wife took the train back to the old alma mater with imaginable pride, and arrived just in time to witness face-to-face their son's most flamboyant disgrace.

On the night before graduation, O'Hara and two classmates went barhopping and got themselves so drunk at a roadhouse that they were detained by a couple of state policemen, who were so entertained by O'Hara's ostentatious blarney that they joined the three students and led them "to places not even the cabbies knew about." When the five had exhausted the alcoholic resources of the county, the officers returned the boys to Niagara Prep just long enough after dawn to be paraded past the fathers up early for their devotions following Mass, walking the campus "reading their daily offices." O'Hara, graduation suit muddied and ripped, slunk to his dorm room to sleep off his binge and was awakened by a faculty member in the company of Dr. O'Hara. The former reported to the drunk that he'd been stripped of all his academic honors, not to mention his diploma. The latter, having been roused with this disgraceful news in his Buffalo hotel room, unwilling to look upon his son for the duration of a journey to Pottsville, ordered him to return on a different train, alone with his shame.

Coldly facing the manifest fact of his son's failure as a student (which confirmed in his view a doom in any favored calling), Dr. O'Hara undertook to drum up a job for him as a utility cub reporter for the Pottsville Journal. "Job" is maybe too grand a word for it. "Apprenticeship," rather, at a starting salary of no

Many, many women adored John O'Hara. He was known as an excellent pence per week, with no raises promised, and even so Dr. O'Hara had to call in a favor from his country-club mate Harry Silliman, the paper's publisher, with whom he'd quarreled, to get his son a foot in the door. But despite the pissant wages of sin, O'Hara understood that a writing job was a step up the ladder from his previous jobs, and from his miserable prospects. Already, writing "A Cub Tells His Story" in May 1925 (his only Journal piece that survives), he was dreaming of swinging for the fences: "I have not been named as the twenty-year-old sensation for anything I have written in my brief career in journalism ... but there is time. I have every hope of winning a Pulitzer Prize, and if I ever get to it, I intend to write The Great American Novel." The dream of Yale finally ended with his father's death a year later. Not because there was no money left to pay the modest tuition, but because there wasn't enough to support those bright college years in the style that was to have been the point of the enterprise. O'Hara was careful to insist that he could have entered Yale in the fall of 1925, that he had been admitted (no documentary evidence supports or refutes the claim, though in 1927 he did write—unavailingly—begging Yale to waive the required board exam, which he had neither passed nor taken) and his mother had agreed to pay his fees. No, it was simply that he wouldn't countenance "washing dishes and tending furnaces." As he later told an interviewer, "I couldn't see waiting on tables and worrying over nickels for four years." dancer and a good talker.

O'Hara, insubordinate and skipping assignments, was regularly scolded and threatened at the Pottsville Journal, to no effect. The managing editor, David Yocum, was short-tempered but long-suffering, owing either to his respect for this young reporter's skill as a writer or to Harry Silliman's sympathy for Mrs. O'Hara. In any case, the miscreant employee—habitually showing up at noon, four hours late, hung over, or not at all—committed serial occupational suicide before his career at the Journal finally expired. During the winter of 1926, O'Hara once justified his tardiness to Yocum by explaining that he'd bumped his head during a bobsledding accident and that this had interfered with his sleep patterns; he then was sent to interview a hinterland weather prophet whose foretelling instrument was a goose bone. When he returned to the newspaper without a story, explaining that the fabled Gus Luckenbill was unknown in his hometown, that marked the end of the reporter's $20-a-week job—or, at least, End No. 1. He begged for another chance, and Yocum relented. Two weeks later, his refusal to cover a Lutheran Church supper on his girlfriend's last night in Pottsville—she was leaving for Montana, to teach at the Flathead Indian Reservation school—occasioned End No. 2, the final finale.

A couple of weeks later he found a job, possibly with Silliman's help, at the Tamaqua Courier, 14 miles northeast of Pottsville. He was bored stiff, but initially dutiful, and soon got a nice raise, from $23 to $35 per week, which he spent on gas, clothes, and fun. When he had funned away his gas money, he'd commute by trolley, and before long he began showing up late, hung over, and ... so forth. In return, the Courier, like the Journal, could not abide him. Now O'Hara was, if not lost, desperate.

However, he had been courting the "Conning Tower" column in the New York World since before his father died, and soon after his discharge from the Courier he got a snippet published, if this unpaid item makes the cut as even a snippet: "As our aboutto-be-assembled book will be compiled from Tower clippings, it is Mr. John O'Hara's suggestion that it be called 'Files on Parade.'" If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere ... Young writers sometimes lean against such slender reeds as a mention in New York, an approvingly lifted eyebrow from an editor or agent, prior to hearing the rest of the story: Sorry, my list is full. Still, O'Hara was in print in New York, and to his mind the rest was mere negotiation. He submitted puns and parodies, imitations and wise-guy observations, which from time to time appeared in "The Conning Tower."

At home he tried to pull his weight. But despite the consolations of his mother's affection and his expressions of responsibility toward his siblings—helping them with homework, offering advice—he was too ashamed to linger long in Pottsville. O'Hara's social standing had dedined, at least in his own eyes, with the death of his father, who, it came out, had badly mismanaged his estate. He showed off his resentments by extravagant displays of scruffiness and foppishness, going unkempt to the country club (acquiring the nickname "dirty-neck," and "dirty-mouth" too) and overdressed to the Log Cabin and Amber Lantern roadhouses.

After the doctor's death, the O'Haras—unable to afford dues— let their affiliation with the Schuylkill Country Club lapse, but John was nonchalant about the formalities of membership. He crashed club dances, sulkingly sucked down too much gin in the locker room, cracked wise, blew his top, sneered, nursed a grudge. Already a nasty drinker and a brawler, he was busy practicing exactly what he later preached to his mentor Walter S. Farquhar, to make inevitable—by forever proclaiming "Fuck you" and "Up yours"—his split from Pottsville. In the early spring of 1928, John O'Hara moved to New York City.

From the top of the bus I would often see footmen in knee breeches opening the front doors of the Fifth Avenue mansions.... I was curious about those town car-and-footman people, but only moderately envious; I somehow took for granted that when I got big Fd have all that too. This was not even a dream or a hope. I just took it for granted.... So my approach to New York was conditioned very early by a fantastic ignorance of money matters, so that when I finally did get there, to work and live, and in spite of the fact that my father had died just about broke—my attitude was that of defenseless optimism. New York would take care of the newcomer.

—John O'Hara, unpublished draft introduction to the 1960 reprint of BUtterfield 8.

New York took care of this newcomer, all right, every which way. O'Hara soon had a job; he'd have many in three years, and if he was inevitably fired from one, he was also reliably hired for another, nine of them. His friend Scott Fitzgerald too famously professed that there are no second acts in American lives. What could he have been thinking? O'Hara, during the time of his rising, caught a new act every few months or so.

He quickly phoned columnist Franklin Pierce Adams at the World, a Pulitzer newspaper edited by Herbert Bayard Swope with more panache than profitability. Encouraged by this conversation to apply for a job at the paper, O'Hara traveled that day to the gold-domed World building on Park Row. Nothing doing, Swope told the petitioner, "we're loaded." So he showed up without an appointment in Adams's office while he was adding arch and faux-archaic miscellany to the next morning's "Diary of Our Own Samuel Pepys," a Saturday installment of the popular "Conning Tower" and a dog's dinner of cultural news, gossip, and quotations. A characteristic sample: "So to Mistress Dorothy [Parker]'s and found A. Woollcott there in the finest costume ever I saw off the stage; spats and a cutaway coat, and a silk high hat among the grand articles of his apparel."

Adams, known as F.P.A., was generously on the lookout for young writers on the way up, and for talented writers stuck at the bottom. He printed—always with full credit—the snippets they mailed him, and in this way did Robert Benchley, E. B. White, George S. Kaufman, and James Thurber first get published in New York. During the past year Adams had used a dozen of O'Hara's observations, parodies, couplets, and whatnot dispatched from Pottsville—not that he was a sweetie or a pushover. Joseph Bryan III, Virginia gentleman—editor, raconteur, and fellow cavalier of the Algonquin's Round Table, not to mention the original husband (much later) of O'Hara's third wife—created a rank order of the most verbally savage wits of this period, "all of them deft with the scalpel and stiletto, and brutal with the bludgeon and blackjack, and each a combination of snapping turtle, cobra, and wolf," and put F.P.A. right up there in a "Murderers' Row" with Parker, Kaufman, and Alexander Woollcott.

In a letter to Robert Simonds, his best friend from Pottsville, O'Hara re-created the scene in F.P.A.'s office. F.P.A. had invited him to sit, then "forgot about me in the excitement of editing." Suddenly Adams began to read aloud, and then asked, "How'd you make out [with Swope]?" O'Hara reported, "No soap. He said 'Sunnavabitch! Isn't it hell?'" With that, Adams phoned an acquaintance at the New York Post and instructed him to hire his new friend. "Oh, a perfect gentleman," Adams insisted. "Can he write? What a question!" After closing that conversation, and immediately before assuring O'Hara he'd also instruct Harold Ross to give the newcomer writing assignments for The New Yorker, it occurred to Adams to ask, "Where is Pottsville?" O'Hara was impressed: "How about F.P.A., huh? Never saw me before and did more for me than anyone but you would do. With him cheering for me I'll get along. Remember what I told you about 1928 vs. 1927? This time next year I'll be somebody."

In the event, the Post didn't hire O'Hara, but a better newspaper immediately did. "The Conning Tower" reported only a few days later—under the rubric "Gotham Gleanings"—that "J. O'Hara of Pottsville, Pa has accepted a position on Ogden Reid's newspaper." That would be the Trib, the Herald Tribune, the HT, the newspaper—despite its rulingclass editorial Republicanism—of literate features and bravura reporting.

As soon as O'Hara was hired, Stanley Walker, the city editor, introduced his young "word painter" to the many regulars at Bleeck's, who spoke of themselves collectively as "the Formerly Club" and their tavern as "the mission" or "the drugstore." James Thurber, who liked to sketch the bar scene there, was devoted to the match game, a guessing contest played for money or, more usually, drinks. Contestants, more than two, would each hold matches—from none to threein their clenched fists, and each would guess the total of all players' matches. He or she who guessed correctly dropped from the game, guaranteed a free drink. The last player remaining bought a round. Bleeck's murals were 10 Thurber illustrations of the intricacies and consequences of this contest. A lively tavern, it was said to be more riotous than The New York Times's favored speakeasy, Gough's, or the Daily News's own Costello's. O'Hara soon had a charge account there, and learned how to use it. The saloon's decor ran to a dictionary for consultation, brass spittoons, and a buckler-andbreastplate set behind the bar. The last soon suffered an injury, a "dent caused by John O'Hara's fist in one of his anti-armor moods," according to a 1984 article by H. D. Quigg. An adage held that "drink is the curse of the Tribune / And sex the bane of the Times," properly honoring the most determined drinkers in New York.

Ol-lara said of the Depression, For what it was wort I had the advantage

of being already broke. "

The newspaper's owner, Ogden Reid, liked to linger at Bleeck's and spring for rounds for his employees. In this context you might imagine that Walker would be unshockable, but his newcomer from Pottsville certainly made an impression, and not the one either might have wished for. Letter after letter from those days finds O'Hara reporting about himself that he was drunk and drinking, on a bender, recovering from a three-day-and-night tear, broke, in debt, up all night baying at the moon or baying at its absence, rising well past midday. In an attempt to save the barfly from himself, Walker assigned him to the morning shift, but it didn't work: O'Hara continued to show up after lunch.

After less than six months, Walker canned him. O'Hara bore him no grudge, a true wonder, perhaps because he could report that Walker "thinks I'm swell and had tears in his eyes when he fired me."

O'Hara didn't mind writing home to brother Tom about the celebs he was running with. The New Yorker's Harold Ross ("a queer duck. Funny stiff German hair and a long gap between his two front teeth. Like F.P.A. he swears all the time and when I say swear I mean swear"), the World's humorist Frank Sullivan, the Trib's boxing writer, Donald Skene, the movie critic Richard Watts (who got decked by a writer he'd panned). The drinkers would begin at Bleeck's, move along to Tony's ("another speakeasy where all the celebrities go"), and then to a nightclub, maybe Chez Florence. "Cigarette girls in satin trousers moved from table to table," as O'Hara biographer Frank MacShane has imagined the flickering, candlelit scene. It was a fluid society, with gamblers and gangsters and showgirls and bond brokers and hustlers and actors and politicians all thrown together, pontificating, laughing, fighting, pairing off, boasting. O'Hara was impressed, not least with himself.

He went directly from the Herald Tribune to Time, probably owing to his companionship at speakeasies with that magazine's Noel Busch and Newton Hockaday. Niven Busch, Noel's older brother, recollecting O'Hara's career at Time, declared that his colleague "had one great piece of luck" at the magazine: "Henry R. Luce detested him." He earned $60 per week and made the masthead, but he continued to resist being at the beck and call of the work whistle, and had imperfectly mastered the technique of leaving a decoy hat and coat on his office rack, to suggest to an importuning editor that he'd just that moment stepped down the hall, when in fact he hadn't yet punched in. Time's managing editor fired O'Hara as soon as his only champion at the magazine, the Busches' cousin Briton Hadden, died. At Which point O'Hara appealed to Henry Luce's sense of fair play, with a predictable outcome. Thirty-nine years later he recalled Luce giving him "that Protestant look" and pronouncing that Luce publications had no place for a rakehell who lolled in bed after nine o'clock in the morning. (Wolcott Gibbs, the theater critic, confirming Luce's discernment, observed from experience that O'Hara had a "strong distaste for sunlight and preferred to stay in bed until the worst of it was over.")

CONTINUED ON PAGE 189

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 157

any, many women adored O'Hara. This is a fact, but it is not self-evident. People unfriendly to him—usually men—were quick to remark upon his coarse face marred by surface irregularities, his ears spread for takeoff, his long jaw, his acne scars, his hammy hands, his bad teeth. Women were attracted, often abidingly attracted. Of his three wives, all remained loyal to him and were unstinting in their affection. He was a baby in his emotions, easily wounded and perverse when injured, and when he was drunk he could be violent. "He took refusals hard," in the understated judgment of Frank MacShane. But he remained close to his mother, to his sisters, and to many female friends. He was curious about their preoccupations, for one thing, and for another he liked to write about strong women. He took for granted their own sexual drives and was disinclined to romanticize them.

A female colleague at Time recalled O'Hara as seedy, with a "mean beard," but he was also capable of refined empathy and tenderness. He liked to make women laugh. He was known as an excellent dancer and a good talker. He was also, early in life, a good listener. Many years later, when he'd explain the histories and customs of their own secret societies to Yale seniors, and fail to invite them to slip in a detail edgewise, he was all pitch and no catch. But the young fictionist in the making, whether by vocational design or inquisitiveness, soaked up what he could learn about strangers, speech, manners, and, always, facts: names, dates, geographies, metes and bounds, titles, liens, weights and measures, yards gained, speed, dollars made and spent, meum et tuum, dowers, goods, stuff.

A reporter friend from that time, Harry Ferguson, encountered him because both men were dating blondes who shared an apartment on East 34th Street. O'Hara's was Katherine Klinkenberg, a stunning "Viking" who worked with him at Time. "When you asked him what he was doing," Ferguson remembered, "he replied: 'I'm a novelist.' John had unlimited contempt for journalism" (though maybe only during that night, since it would pass). After serving bathtub gin from pint milk bottles, the women sent the two of them home, but along the way Ferguson was led up a flight of stairs into a Second Avenue speakeasy, where, after an exchange of good-mornings with the bartender, O'Hara ordered rye on the rocks, "and my friend will pay." Indeed, Ferguson "paid and paid, because O'Hara turned his pockets inside out to demonstrate to me that he had no money." Thereafter, Ferguson financed many a bender, but his friend always repaid him, "usually with witty notes accompanying the money." Besides, the financial drain of that "costly night" was worth it, "because for the first time I saw the incredible O'Hara Memory Machine in action."

The newfound sidekicks shared the speakeasy that morning with four other patrons, who were arguing about sports. "One of them kept yelling, 'All right, name the infield, name the infield; five bucks says you can't do it.' " The subject was the 1919 Black Sox scandal, when Chicago threw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. O'Hara took the bet, or, rather, took $5 from Ferguson to take it. "So there was ten dollars on the bar and tension in the air. O'Hara knocked back a shot of rye and spoke: 'First base, Chick Gandil. Second base, Eddie Collins. Shortstop, Swede Risberg. Third base, Buck Weaver.'"

The losers tried to recoup, challenging him to name two outfielders, two pitchers, and the catcher. Another sawbuck pocketed. The losers were now broke themselves and moving sullenly toward the stairs when one called over his shoulder that O'Hara must have been born and raised in Chicago. No, O'Hara said, Pennsylvania, and then for good measure declared himself a Philadelphia Athletics fan "and a cousin fourth removed to Mister Connie Mack, their manager."

In July 1929 he was a night rewrite man A for the Daily Mirror, but that job called for his appearance in the office at twilight, interfering with his intake at Racky's, a speakeasy a block distant from the Hearst tabloid. "A job was something that, if you didn't keep it in its place, could get in the way of the really important business of living it up," a pal of the time remembered of O'Hara's work ethic. O'Hara himself many years later remembered it this way: "The study of the Martini as prepared at Racky's restaurant, a block from my office, was an enjoyable way to start my day, which was supposed to begin at 6 P.M. Unfortunately for journalism, although happily for my social life, the day side of the Mirror would be at Racky's, on their way home, just when I was on my way to work.... I hated to leave the Mirror. The city editor had a Pierce-Arrow roadster and wore silk shirts, and while I would have chosen a Lincoln phaeton and button-down broadcloth, the idea was the same. There was money to be made."

O'Hara wasn't making much of that money, but he was spending a good sum. Frank MacShane has justly concluded that "because he cashed his paychecks at bars he tended to spend everything he earned right away and looked upon the resulting impoverishment as an act of God over which he had no control." He earned, when he was working, four or five dollars a day. Yet he patronized the theater and enjoyed watching Fred and Adele Astaire dance at the Trocadero. A miserable room cost a dollar, a steak dinner a couple of dollars, a pint of whiskey roughly a third of his weekly salary. He ate and drank more modestly at the Type & Print Club, where Trib typesetters liked to gather, and where he met John K. Hutchens, son of a Montana newspaper editor. (Hutchens was beginning his long career as the Herald Tribune's, literary critic, and the two men's loyalty to each other endured, and ameliorated some of the pain O'Hara suffered from many unfriendly and influential critics during the next four decades.) The man-about-town ate and drank more expensively at Tony's on West 52nd, where the owner, Tony Soma—in the memory of Finis Farr, author of O'Hara—might sing an aria from Verdi or Puccini while standing on his head. He could dine even more lavishly at Jack and Charlie's, down the street at 21 West 52nd.

And then there were the nightclubs, the Pre Catalan or the hotel roofs where Paul Whiteman played, and the Dorseys and Guy Lombardo, or the Onyx Club, where the best white jazz musicians—Miff Mole and Max Kaminsky, Johnny Mercer and Phil Napoleon—jammed. O'Hara met Dorothy Parker, later his loyal pal and most admiring fan, listening to the Hawaiian house band at an all-night joint called the Dizzy Club. He also frequented the Owl, which served the hardest of hard-core soakers, patrons who showed near dawn and drank till noon. Farr has invoked the clientele as people "who drank fast, said little and had pistols under their coats. Others were there only because they did not want to interrupt their consumption of alcohol, except when unconscious, until they died." One infamous young customer announced to fellow barflies that he had just enough money to drink himself to death, which he had, and which he did. This was the beginning of what the narrator of BUtterfield 8, O'Hara's second novel, set in New York, terms the "elaborate era" of speakeasies.

There were consolations. In April 1928, soon after he was hired by the Trib, he had a story accepted by Harold Ross at The New Yorker. The publication on May 5 of "The Alumnae Bulletin" began an association remarkable for its storminess, but even more for the flood of stories and sketches and novellas that surged from O'Hara to that most cosmopolitan of periodicals, about 250 between "The Alumnae Bulletin" and "How Old, How Young" (1967), his final New Yorker piece. The first published sketch is a brief and sour monologue by a woman responding to a questionnaire from her Seven Sister college for its alumni notes, a slight exercise in up-to-speed diction. He cashed the $15 payment check at Bleeck's; as the bartender forked over the money, which would so soon be coming right back at him, he was heard to ask another patron, " The New Yorker—what in hell is that?" Today—when the magazine's every staffing shift commands headlines—it seems remarkable that anyone should have had to ask. Three years after its founding, on uncertain financial ground, The New Yorker was well on its way to becoming a national intellectual and literary phenomenon. By the time "The Alumnae Bulletin" appeared, Harold Ross's staff included Robert Benchley, Wolcott Gibbs, Dorothy Parker, James Thurber, Katharine Angell, and her second husband, E. B. White—people who became crucial to O'Hara's career and his sense of himself. He came to measure himself by tokens of the esteem in which he was held by Ross and by his colleagues.

As he shinnied up The New Yorker's, thorny pole—selling 12 short pieces during 1928—he was slipping fast at the Daily Mirror. His high-water mark came in an unbylined feature, "Girl Invades Yale Club Bar, Only for Men," which merely amplifies with a name and a date its headline. (It's odd that O'Hara believed the event to have been more newsworthy, or amusing, than his own invasion of that bar, but irony was never his greatest strength.) He was fired from the paper for the usual reasons: too often tardy or absent, too often flagrantly drunk or hung over. He got hired by Benjamin Sonnenberg's PR. firm to cover a bridge match but never showed up, and his one-day employment ended when Sonnenberg tracked him to a speakeasy, the Homeless Dogs, where O'Hara had passed out.

After the stock-market crash, he picked up work as the fabulously generous Heywood Broun's secretary early in 1930. Broun, a columnist for the World and an idol of O'Hara's, liked to eat and drink and talk, and he paid for O'Hara to eat and drink and talk with him. (When Broun died in 1940, O'Hara wrote a letter to The New Republic crediting Broun with a paramount influence: "I still have a raccoon coat for the excellent reason that at my age Heywood Broun had one too.") The Great Crash has been described by one witty friend of O'Hara's as the vanishing of huge fortunes of "notional" money. Finis Farr concludes, with raffish simplification, that "this money had never in fact existed, but its reported disappearance caused distress." O'Hara boasted of his indifference to the calamity: "For what it was worth, I had the advantage of being already broke."

During the late spring and early summer of 1930 he scraped up work as a movie critic and radio columnist (under the name "Franey Delaney," in a tip of the hat to his maternal grandparents) for the Morning Telegraph, a grubby sheet specializing in racing news and professional bulletins about the entertainment biz. O'Hara, drifting from one dismal little room to another, didn't own a radio, so he covered his beat from bars that did. He wrote especially vividly about jazz, about Louis Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson, but this newspaper was as distant from the Trib as it was possible for a Manhattan newspaper to be, and some index of its standing is offered by the fact that he accepted the job only after failing in his quest to join a newspaper in Trenton, New Jersey.

Although he worked as a movie publicist for Warner Bros, and RKO after his inevitable sacking by the Morning Telegraph— tardy and drunk—he was repeatedly pulled toward daily journalism. In his own erratic way, by his own timetable and imperatives, he was a pro. In a 1955 interview with John K. Hutchens for the Herald Tribune, he told the truth: "I pride myself ... on never having missed a deadline. I have failed to show up for work, and separated myself from a job that way. But if a story was due at 10:10, I had it all in by 10:09." Forty-one years after being taken on as an unpaid charity case by the Pottsville Journal's publisher, looking back in My Turn, a collection of columns he wrote under that name for Newsday, O'Hara wrote about his lifelong gravitation:

"The moment I enter a newspaper office I am at home, not only because the surroundings are as familiar to me as backstage is to an actor, but because, like the actor, I am ready to go on in any part. I could write a headline, take a story over the telephone, cover a fire, or interview a movie queen, and if I had to make up the front page I could do that too, although I might not win the N. W. Ayer Award for it."

Just like him to know—and drop— the exact award he'd have been pissed off not to have received for his makeup skills. For all his comfort in daily newsrooms, newsrooms weren't comfortable with him. But for a long time he would appropriately identify himself as connected with—and a slave to, at a dime a word— The New Yorker.

It is notable that the writer who was too A "experimental" for the Jazz Age New Yorker was later turned on a spit by critics derisive of his expository clunkiness, his interminable explicitness. Maybe, by the time of the long novels—A Rage to Live, From the Terrace, Ourselves to Know—he had learned Gibbs's and Ross's lessons too well. But in the meantime, after a few years writing for the magazine, he began to refine his art, as Gibbs understood it, and "lost much, though by no means all, of his earlier passion for indirection. One recent story, for instance, ended with its protagonist leaving the room with the bow on his hat on the wrong side of his head, and, while it was abundantly clear to Mr. O'Hara that this indicated great spiritual turmoil, it conveyed precisely nothing to many readers, who wrote in, irritably." It is also a fact that whether a hat's bow showed on the wrong side mattered crucially to his characters; right side's wrong, right?

O'Hara's temperamental and circumstantial fragility at this time cannot be exaggerated. He was a hostage to his compulsions, his ill temper, his preposterous and heroic pride. He was a prisoner of poverty, which during 1930 grew alarming. He was reduced to sleeping on couches, and even to mooching off an aunt and uncle in East Orange, New Jersey. His hangovers were a chronic illness now, and he was picking more fights than he won. The sketches he submitted to The New Yorker during this period attested to his despair and isolation, his Darwinian anxiety that maybe he wasn't among the fittest after all. He was chagrined to have been unable to give more—in coin or esteem—to his siblings and mother, and his girlfriend Margaretta Archbald had accepted a proposal of marriage from a rival. When even the lowly Telegraph showed O'Hara the door, he signed off in his final column with "Te morituri salutamus," a dog-Latin misquotation of Suetonius's "Ave Caesar" valediction. Then, shortly before Christmas, he limped home to Pottsville.

What happened to O'Hara in Pottsville during the following dark months of soulscouring can't be specified, but it's reasonable to guess that he sounded a kind of abyss. Writers—or anyone who has suffered the flu—will recognize that odd state he must have entered, a numb reverie not unlike the fevered sweats Keats endured from consumption, and an extraordinary out-of-him-selfness (gussied up in Keats's case as selfless "poetical character ... not itself ... everything and nothing," having "no Identity," continually "filling some other Body") physiologically congruent with the creative state. Keats complained that "I am in that temper that if I were under water I would scarcely kick to come to the top." But the reason his state then is available is that he composed it, considered an order of words that would reveal it, and by this process kicked right on up to the top. Although O'Hara sank into an overstuffed chair moping and despairing—from his brother Tom's vantage—he was also feverishly trying to place work at Scribner's Magazine, sending proposals and reams of pages to editor Kyle Crichton. Charles Scribner—book publisher of Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and Ernest Hemingway—had one of the three magazines that, with The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, might be suited to O'Hara's preoccupations and gifts. When he submitted to Scribner's stories that had been declined by the other two, he was candid about their histories, even telling Crichton why they had been refused—too oblique, too limited in range, too dirty.

At the end of the Washington's Birthday holiday in 1931, O'Hara's brother Joe drove him to East Orange, and six days later, on February 28, after a cycle of flamboyant New York parties culminating in a ceremony hatched at a speakeasy, John married Helen Ritchie Petit at the city hall. He and "Pet" had met, at a New York Equity Ball, no more than a couple of months before they married. Slight, with a delicately boned face and deep-blue eyes and gold hair to her waist, she was 22, an aspiring actress, a graduate of Wellesley who had studied at the Sorbonne and had an M.A. from Columbia. Several interviewers got dissimilar versions of her character from different friends. If one declared that her Wellesley classmate was "fastidious," another noted that her clothes often seemed to need cleaning. She was said to have had an Alice-inWonderland air, or else to have been "jumpy." She was bright and witty, and was accused of indulging in enigmatic conversations that were onerous to follow (maybe only to friends who were not bright and witty). There was general agreement that she gave off an "iridescence," and O'Hara is quoted in Finis Farr's biography as remarking that "she had a shine all around her." Pet played the ingenue opposite Eddie Albert's lead in Room Service, the successful Broadway farce.

An abrupt reversal of fortune came in the form of a $1,000 gift from Pet's uncle, earmarked for a honeymoon. The couple considered Paris, and then—thinking practically and productively—they settled on a trip to Bermuda, to the end of giving the new husband a serene and healthful situation for his work. (Wolcott Gibbs had taken his wedding trip to Bermuda, and this encouraged O'Hara's interest in the island.) By the end of June they found themselves at Paget East, in a two-bedroom yellow cottage near Elbow Beach. The rent was $50 per month, and they immediately settled into a routine of reading, and he into steady, groundgaining writing. They walked, rode bikes, kept regular hours, and—in the miraculous manner of work's potent cures—forgot to drink themselves silly.

In a letter to Bob Simonds, mailed a couJ-ple of weeks after they arrived, O'Hara described the routine: "We just don't drink. No resolutions or anything of the kind. It just doesn't seem to occur to us. We bought a bottle of gin when we got here, and we still have it, two weeks and one day later. Pet reads, and I have done a lot of writing. We eat and smoke, and at night we sometimes knock off a bottle of ale and a bottle of porter, and that's just about our life. I bike to Hamilton (about twelve minutes going, fifteen coming back on account of a hillock) once or twice a day to mail letters and buy the papers and magazines and cigarettes. I haven't even got a sunburn.... So far I have resisted the impulse to buy a pith helmet, but I do wear linens or flannels all the time."

The O'Haras returned to New York in the fall. John wrote to Simonds: "Mrs. O'Hara and I have done a good deal of drinking since Bermuda, you will not be interested to know. We have a nice enough apartment; very likely will look very lupine when the rent comes due, which is Dec. 1, thus leaving me flat on my ass for Christmas, which is as it should be. It will be something not to have to be sorry about not giving Christmas presents this year. I've been sorry so many years that it almost spoiled my holidays."

It was not a good marriage. John quarreled bitterly with Pet, jealous, to an acute degree, of imaginary rivals, or of his wife's imaginary flirtations with actual friends. Let her speak to any man at Tony's or Bleeck's and O'Hara would accuse her publicly of laying plans to sleep with that man. She complained to her friends that life with him was becoming "unendurable." He, meanwhile, mocked his wife's theatrical yearnings. James Thurber's second wife summarized O'Hara as "a cruel and neglectful son of a bitch," and on the subjects of drunken fury and viciousness, she has to count as a connoisseur. Her own husband was repellent.

By the autumn of 1932, O'Hara was on the skids again. During that year, he sold 10 stories to The New Yorker and one to Scribner's. He earned at least $5,000, including his up-till-then record payment of $ 175 from The New Yorker for his profile of a chorus girl, "Of Thee I Sing, Baby." This was much money then, and added to Pet's allowance it should have been enough. Reason not the need. The theater cut deep, dinner after the theater, nightclubs after dinner, taxis home. They were tapped out. His phone had been disconnected, and not for the first or last time that year.

And then Pet, at her mother's insistence and against O'Hara's wishes, had an abortion. He felt bitter shame. He never expressed anger at his wife for her decision; that he reserved for petty torts and imagined wrongs. But he felt pain that his failures, his unreliability, had inspired in his wife such a conviction of hopelessness, and now he indulged even more in prolonged benders, what he called "overnight vacations; getting so cockeyed drunk that twenty hours elapse before I recover." In a heartbreaking throwaway sentence to his best old friend, with whom he'd shared his longings and hubris: "I wish I could take a vacation from myself."

Trouble outran him. In his distress and regret he was increasingly churlish. When an old Pottsville friend visited the couple, a drunken O'Hara dressed him down as a social climber and refused to shake his hand when he left. When the friend phoned the next day to invite O'Hara to dinner to make amends, Pet went in his stead. And then she went farther—home to Mommy.

Hara applied for a job as managing editor of the Pittsburgh Bulletin-Index, a New Yorker knockoff among the many that had sprouted in such get-up-and-go American cities as Los Angeles, Cleveland, and Chicago. He was by now convinced that New York would, in the aftermath of his breakup with Pet, not only lick him but kill him. O'Hara wrote the owners, J. Paul and Henry Scheetz, a detailed proposal that was frank about the shortcomings of the issue he had been sent for study.

The Scheetzes were evidently kinsmen in masochism, because the surly supplicant got the nod and began work in May. He negotiated a $50 weekly expense allowance at the William Penn, where he set up housekeeping on the 12th floor, sharing a room with his typewriter and golf clubs, weapons with which he meant to bring the Iron City to its knees. Pittsburgh had been ground down by the Depression, but an outsider wouldn't have known as much from the spring and summer seasons' polo matches, coming-out parties, fancy-dress balls, and fox hunts. From his office a few blocks from the hotel, in the Investment Building, O'Hara commanded a staff of two, paid $7 and $8 per week, about the price of the Brooks Brothers neckties with which he wowed the boys. At least one of these, Frank Zachary, later remembered O'Hara as a considerate boss, and impressively fast on the keyboard whacking out stories for the B-I, as it was called, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair, which finally accepted a story, "Hotel Kid," while O'Hara was in Pittsburgh. Zachary told Finis Farr that it seemed to him O'Hara "could finish one of these before going out for lunch."

Let it be noted that he was deep into the fiction that became "The Doctor's Son," probably his greatest short story, and a thoroughly autobiographical one. In the meantime, the market for facility and cleverness was drying up in Pittsburgh. The bar bill at the William Penn was the least of it. O'Hara had created a small scandal with a recently married local woman, according to Matthew J. Bruccoli, author of The O'Hara Concern, and his employers were weary of his undisguised scorn, and of his habit of writing on the B-I time clock submissions for fancy New York publications.

In early August there was an office dustup. Bruccoli reports that the incident grew in legend to a fistfight, that O'Hara was said to have "knocked one of the owners across a desk, but it probably involved only pushing or shoving." At any rate, he quit without notice and had his things shipped to New York. Pet was with her mother in Nevada, where she divorced him on grounds of extreme mental cruelty. Within days he had settled into a tiny, $8-per-week room at the Pickwick Arms Club Residence, 230 East 51st. Now he was ready to ready himself for Appointment in Samarra.

He spent his time in New York in the company of Gibbs, Benchley, and Dorothy Parker. By now she was his best friend, and her influence was decisive on his determination to go forward with his novel. There is every reason to believe that her goodwill toward O'Hara was unconditional. She much later told the New York Post's debunker, Beverly Gary, that John was a "talent that blazed, but he hadn't yet steadied himself as a writer" before the composition of Appointment in Samarra, which she tirelessly promoted. He was "broke and depressed and needed to be nagged." When he reported that Ross had turned back a piece, leaving him strapped, without a word she got up and wrote a check so that he could spend a weekend in the country with Pet, with whom he remained on friendly terms. (In the event, he used the money to liberate his winter wardrobe from hock at Macy's.) According to her biographer Marion Meade, Parker "ordered him never to mention the matter again, because she was so deeply in debt that fifty dollars made no difference." There seems to have been no physical attraction between them, and he was no match for her verbal-fencing speed and wit, a word attached like a title of nobility to her name, Her Wittiness Dorothy Parker.

In addition to a tendency toward dark moods, which Parker termed "Scotch mists," they shared admiration for F. Scott Fitzgerald, who by 1933 needed all the admiration he could get. Wolcott Gibbs wrote that This Side of Paradise was "a sort of textbook" for O'Hara, "to be reread at intervals." The most touching of his fan letters to Fitzgerald followed the death of Ring Lardner, a great influence on Parker's despairing, deadpan stories, and for whom Fitzgerald had written a memorial in The New Republic. O'Hara detailed how he had heard of this essay at Tony's, from Thurber, who was praising it. He had gone to an all-night newsstand to buy it, and the news seller, explaining that the issue had already been taken off the stand and bundled to be returned, added in an unlikely aside, "You want it for the article on Lardner, I guess." An issue was extracted from the bundle and read "over and over." The next night he gave the magazine to Parker, and the two removed to a beanery—the Baltimore Dairy Lunch. She "wept tears." O'Hara admitted to Fitzgerald that all he could think to say was "Isn't it swell?" This made Parker bristle, and say, "The Gettysburg Address was good too."

J11 his may explain his tolerance of Fitzger-L aid's bad behavior. Not long after getting that fan letter, Fitzgerald came to New York from Maryland to drink with the gang at Tony's and to meet pliable young women. At the end of a night of drinking coffee, and watching Parker and Pet and Fitzgerald drink what they drank, O'Hara found himself in a taxi with his two friends and his ex-wife. "Very late," as O'Hara remembered the scene 30 years later in a letter to William Maxwell, the writer and editor, "on the way to [Pet's] apartment, Scott was making heavy passes at [her] and she was not fighting him off." At this time Pet lived in a swank Park Avenue building, and Fitzgerald, propped up by the doorman, followed her into the foyer, pawing at her. "Meanwhile Dottie had said to me, 'He's awful, why didn't you punch him?' I said [Pet] seemed to like it and we were divorced." Now, it is also true that O'Hara didn't want to leave the taxi, as he was afraid that the doorman would report his presence to Pet's mother. But given his aggravated jealousy, it might be expected that such a drama would have called out O'Hara's blackest rage. Maybe coffee canceled it, or maybe his knowledge of Fitzgerald's brittle vulnerability in the final days of submitting Tender Is the Night (whose galleys O'Hara had proofread) spoke to his insecurities about his own novel. Thirty years later there is not even a tinge of disdain in his speculation to Maxwell that Fitzgerald probably had listed Pet "among his conquests."

This was the beginning of 1934, 25,000 or 30,000 words into his novel, and O'Hara's billfold was cleaned out. He wrote his brother Tom that he had begun to get "little notes, then bigger notes, from the proprietors of [the Pickwick Arms], reminding me that the most important rule of the place was Payable in Advance." He anguished about eating, let alone paying his room rent. He tried to wheedle money out of Harold Ross, reviewing his productivity (more than a hundred "casuals," or short humor pieces, printed!) and tooting his own muted horn— the "good pieces I wrote have been recognized ... and the bad pieces have been forgotten by my enemies." He suggested it might be appropriate to give him a bonus of a dollar per casual.

Then O'Hara took a more direct approach. He sent special-delivery letters to Harcourt, Brace, to Viking, and to William Morrow, offering to show them what he had written, in return for their agreement to read it and decide overnight whether to advance him living expenses while he finished the book. Having mailed the letters, he spent all day in nickel-and-dime movies near Times Square. All three publishers replied by telephone that same afternoon, and O'Hara chose Harcourt's Cap Pearce, because he had phoned first; the next day, during a visit to the publisher, Alfred Harcourt asked a single question: "Young man, do you know where you're going?" O'Hara assured him that he did. The advance was $50 per week for eight weeks, a sweet deal for Harcourt, a lifesaver for the young man. If he hadn't begun this submission draft till December, he had written a thousand words per day, a fine run even for him. Writing to Tom in early February, he described his regimen: "What I am doing now is stalling. I work in jags. I work like the devil for days at a time, and then suddenly I dry up or get stale, or get physically too tired to go on."

nPhe book was due April 1, an absurdly -L tight schedule but well suited to O'Hara's pell-mell preference. There's always in the writing of a novel the difficulty of ongoing revision, of amending on page 200 of a manuscript a detail which creates a trickleback adjustment to myriad tributary passages upstream. This is such a fundamental feature of longer work that novelists come to learn quickly that memory of the details of the text is a friend easily betrayed by inattention. Familiar now with computers, novelists speak of loading their work into memory each morning, as though it were as simple as punching a few keys. How this is done, in fact, is either by rereading it after each interruption or by uninterrupted concentration, carrying the novel forward regardless of side jobs covering football games, appearances at writers' conferences, or days abed recovering from hangovers. If the novelist can't evade these interruptions, he or she must, before pushing forward, fall into the dream of the narrative voice, and maybe once in a lifetime a novelist manages to remain unjolted from that odd trance. And this is how it happens—as it did to William Faulkner with As I Lay Dying, for instance—that a finely joined novel may be fashioned in a matter of weeks by a writer normally requiring years for the same achievement. Owing to poverty, or fruitful compulsion, or good artistic instinct, O'Hara drove through Appointment in Samarra in an ecstatic reverie.

In March, even the solitude of the Pickwick Arms wasn't solitude enough, so he sailed with his typewriter on the cruise ship Kungsholm, bound for Barbados and the eastern Caribbean. He was, this hot new property of a venerable New York publisher, the chief contributor to The Kungsholm Cruise News—editor: John O'Hara. Well, nobody ever promised that writing would be a predictable profession. The job aboard, he claimed, required 20 minutes of his day, and the chatty newsletter shows it.

Even on the Kungsholm and a victim of his own baneful influence, he couldn't be stopped. Back on dry land in New York, he surrendered the novel April 9, one week late. With five bucks and change to his name, he wrote Tom that day to confess that he was afraid he'd "muffed the story." This is not an unusual response—postcoital tristesse, postpartum blues—to the surrender of a book to an editor. What was unusual was O'Hara's persistent underestimation of Appointment in Samarra, a book from which he might have taken more pleasurable pride and better instruction about the peculiarities of his narrative strength. Just now, he received from Fitzgerald an inscribed copy of Tender Is the Night, and in expressing his awe of that novel's ambition, O'Hara felt the need to diminish that of his own, falsely confessing that "the best parts of my novel are facile pupils of The Beautiful and Damned and The Great Gatsby. I was bushed, as Dottie [Parker] says, and the fact that I need money terribly was enough to make me say the hell with my book until you talked to me and seemed to accept me. So then I went ahead and finished my secondrate novel in peace. My message to the world is Fuck it." Clearly he had enjoyed crucial encouragement from Fitzgerald, but The Beautiful and Damned ran out of oxygen before it reached base camp beneath Appointment in Samarra, and why couldn't O'Hara judge accurately what he had made? Perhaps because the unobstructed directness and primary colors of his sentences lack the music and prettiness of Fitzgerald's least efforts, and because he now understood that accuracy of recollection and description was to be his literary destiny.

T)erliaps he also felt too acutely like an JL apprentice among his admired friends. The novel's title was another hand-me-down from Dorothy Parker. One afternoon at tea in her apartment, after reading and admiring O'Hara's pages, she pointed him toward a possible epigraph, in W. Somerset Maugham's play god-awfully entitled Sheppey. The passage tells of the encounter in the Baghdad marketplace between a merchant's servant and the female Death. The servant, jostled by Death and startled by a shock of recognition on her face, flees, riding his master's horse north to the putative safety of Samarra. What a coincidence! Death had been surprised to see that very servant in Baghdad, "for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra."

O'Hara, studying the passage, said, "There's the title for my book."

Dorothy Parker, according to him, said, "Oh, I don't think so, Mr. O'Hara."

Alfred Harcourt—suggesting, with an unpersuasive quorum of Harcourt, Brace editors, that he call his first novel Swell Guy— abhorred the title. So did Sinclair Lewis, who called it "atrocious philosophy, and— since it is both meaningless and difficult to remember—shockingly bad box-office." I think it's a fine title, tantalizing and appropriately deterministic, which is, I suspect, what Lewis found so "atrocious." "I bulled it through," O'Hara later boasted in an author's preface to the Modern Library edition of the novel. It was thereafter a mark of his nerve, if not of his judgment, that he looked only to himself for literary counsel, just as his successful auction of the novel to three publishers caused him to overvalue his cunning as a literary agent.

L1 ven as he undervalued the virtues of Ap1—jpointment in Samarra, O'Hara thought of himself as playing in the same league with the best of his contemporaries. "Fine"—as in "It was a fine night"—has been "a romantic word" in the vocabulary of Julian English, the novel's hero, ever since he read A Farewell to Arms; an offstage character's only distinction was that he had known Scott Fitzgerald at Princeton, "and that made him in [the heroine] Caroline's eyes an ambassador from an interesting country." Fitzgerald returned the favor of O'Hara's unstinting admiration with a blurb, and Hemingway wrote in Esquire that he was "a man who knows exactly what he is writing about and has written it marvelously well." Thus began a sequence of logrolling that climaxed with O'Hara's notorious 1950 review on the front page of The New York Times Book Review of Across the River and into the Trees, in which he judged Hemingway "the outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare." For this panegyric he would be made to pay, not least by its beneficiary. Perhaps Papa was sore about a New Masses review of Appointment in Samarra, which claimed that "O'Hara reports like Sinclair Lewis and has more guts than Hemingway."

For whatever reason, Lewis himself— whom O'Hara had so admired—lit into Appointment in Samarra in the Saturday Review, the magazine's second hostile response. The first, by its editor, Henry Seidel Canby, was titled "Mr. O'Hara, and the Vulgar School," a slightly less brutal attack than the one by Lewis, who had twice commended the novel in pre-publication squibs (a notunheard-of paradox suggesting that he loved his fan's book until he read it). His condemnation was comprehensive, beginning with the title, which, he wrote, might as well be Assignation in Abyssinia, and priggishly summarizing its sensuality as "nothing but infantilism—the erotic visions of a hobbledehoy behind the barn." O'Hara later tried to badger Lewis at '21,' standing beside him at a urinal, but his quarry fled, and he was obliged to content himself with a nasty little sketch in BUtterfield 8 of a writer almost as sad a drunkard as Lewis getting shown the wrought-iron gate by the fed-up management of that celebrated hangout. To O'Hara's credit, however much he came to despise the man, he continued to admire and emphatically praise Lewis's work.

Appointment in Samarra, dedicated to F.P.A., works the author's mentor into the action by way of a plug for his column in the World and for Adams's wisdom overall. Adams naturally—the way of the World— returned the favor, with interest, in a "Diary of Our Own Samuel Pepys" entry: "So home, and read all the afternoon John O'Hara's 'Appointment in Samarra'... with some of the best talk, especially between husband and wife, that ever I read, and I got a great glow of pride when I saw that the book had been dedicated to me." Six days later, another hooray: "Boy, I yell for 'Appointment in Samarra' / A dandy novel by John O'Hara."

John O'Hara was 29 when he published Appointment in Samarra. He would live another 36 years, produce 15 more novels and 14 collections of short stories, as well as the book for the Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart musical Pal Joey, based on his own stories. He would marry twice more, and have one child, a daughter, Wylie, with his second wife. Though an association with Yale would always elude him, he lived the last 20 years of his life in Princeton, New Jersey, in the shadows of the reinforcedconcrete spires and faux gargoyles of the wrong great university.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now