In historical paintings, what do women with swords represent? Their historical taking up of arms reclaims traditionally 'masculine' acts of bravery and brutality.

Such images redefine what power can look like in the hands of a woman. The armed woman challenges the gender norms of her time or embraces them in ways that assert her femininity, leadership and power. This contrast endlessly captures our collective imagination.

Yet this fascination and its representation in art is often a double-edged sword. Have they been represented as exceptional heroines or gender transgressors? Empowering figures or cautionary tales?

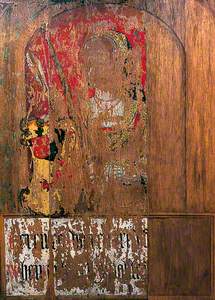

Lambert Barnard's nine Amberley Queens (1526) are dressed to kill. These 'Heroines of Antiquity' wear elegant courtly dresses alongside ornate arms and armour. Their courtly and battlefield attire establishes them both as queens and military leaders, like Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, who led vast invasions to expand her empire and made herself Empress in AD 272.

Zenobia

(from the Amberley Castle 'Heroines of Antiquity') (Amberley Queens) c.1526

Lambert Barnard (c.1490–1567)

Or the legendary Queen Semiramis, who directed vast military campaigns at the head of Assyria. Meanwhile, Hippolyta and Menalippe display their combined elegance and strength as Queens of the Amazons. The legacy of these legendary warrior women has lived on via heroines like the superhero Wonder Woman, who first appeared in comic books in 1941. And in many ways, these nine women represented the Wonder Women of their time.

Semiramis

(from the Amberley Castle 'Heroines of Antiquity') (Amberley Queens) c.1526

Lambert Barnard (c.1490–1567)

The historical personification of male heroism and chivalry, the Nine Worthies, represented men from pagan, Jewish and Christian backgrounds. In contrast, the female equivalent, known as the 'Nine Worthy Women' represented so-called 'feminine' values such as mercy and chastity. Their arms and armour would be symbols of moral virtue as much as symbols of their military exploits, thus creating an interesting visual contradiction.

Here the Greek mythical figure of Cassandra (never a fighter in the original siege of Troy) is shown with more armour than the warrior Amazons!

Cassandra

(from the Amberley Castle 'Heroines of Antiquity') (Amberley Queens) c.1526

Lambert Barnard (c.1490–1567)

These queens may have been chosen and painted for another queen – Catherine of Aragon's planned visit to Amberley Castle. Hippolyta carries a bow, an arrow-sheaf with a single arrow and wears a Tudor headdress. The arrow-sheaf of Aragon was Catherine's personal symbol, and the headdress a direct nod to her own style at the time.

Hippolyta

(from the Amberley Castle 'Heroines of Antiquity') (Amberley Queens) c.1526

Lambert Barnard (c.1490–1567)

Furthermore, she could have identified with this warrior queen. In 1513, Catherine was Regent of England in Henry VIII's absence, raising an army to fight off James IV of Scotland. She rode to meet the army at Flodden, with artillery support and 1,500 suits of armour.

According to legend, she not only addressed the troops in full armour, but she did so while heavily pregnant. Catherine never ended up visiting Amberley Castle. Yet she may have appreciated a reference to her military legacy, which ultimately defined her as far more than Henry VIII's (first) wife.

Unlike the Nine Worthies, the identities of the Nine Worthy Women were ever-changing. One of them was sometimes the Biblical figure of Judith. This Jewish widow seduced the Assyrian general Holofernes, whose army threatened the Israelites.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

c.1598–1599, oil on canvas by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Once Judith lulled him to sleep with wine, she beheaded him – ensuring her people's victory. First depicted as a warrior woman in armour, this shifted in the late Renaissance and Baroque periods. Artists such as Caravaggio focused on what she wore to seduce her target, so that Judith's femininity became as important as her sword-wielding act of heroism.

In this copy of Christofano Allori's original painting, Judith is a picture of poise and beauty. She would have come off as 'heroic enough' but 'feminine enough', patriotically completing her mission.

Yet in Lucas Cranach the elder's interpretation (1530) Judith is rendered ambiguously. She is depicted wearing the latest fashions and displays her sword, while presenting her trophy with a smug smile. A woman who is aware of her power, is she a heroic saviour or femme fatale? Judith was sometimes interpreted negatively because of her sexuality and cunning. A few depictions show her using her sword yet also diminish her aggressiveness, possibly so she wouldn't be perceived as too masculine.

Giuditta che decapita Oloferne (Judith Beheading Holofernes)

1614–1620, oil on canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653 or after)

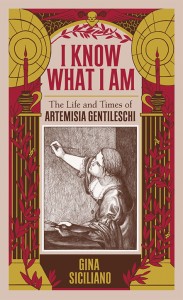

Artemisia Gentileschi flips this narrative. Her Judith (1614–1620) is fiercely determined, with blood splattering her chest. Some see this image as a way for Gentileschi to reclaim her own agency and power against a male figure who could have represented her rapist. Its violence shocked at the time. Yet we see it now as a feminist statement from a woman artist who fought to establish herself in a field dominated by men.

Sword-wielding and weaponised femininity link Judith to another Biblical beheader: Salome.

Her dancing at a feast thrown by King Herod led him to offer her whatever she wanted. She asked for the head of John the Baptist, which was eventually served to her on a plate. Lucas Cranach the elder's sixteenth-century depiction of Salome, like Judith, shows her elegantly dressed and seductive. Her sensuality is her only direct 'weapon'.

In many works of art, she is usually shown either dancing or showing off her head-laden plate. Yet some depictions show her as the sword wielder herself.

In this nineteenth-century sculpture by Charles Octave Levy, Salome is ready to unsheath her sword.

She is both seductive and murderous, made more sexual through her menacing gesture. This contrast between violence and sexuality would have fascinated many artists at the time. Here Salome is also a villain complete control, despite earlier versions showing her as a pawn manipulated by her mother in causing the murder.

The narratives of Salome and Judith remind us of sexist double standards perpetuated by male artists when representing these women's stories. Asserting femininity while wielding a sword is celebrated as long as this femininity is not seen as disruptive, dangerous, or transgressive. Women's abandonment of submissive femininity and transformation into fighters and murderers is only tolerated when they are committing treacherous acts on behalf of their family or country.

This brings us to Joan of Arc, whose voice of resistance famously led her to don armour and take her place within the Hundred Years' War to lead France to victory.

The vision of Joan in armour became a symbol of resilience and hope. Yet her transgression of gender norms led to her death – she was burned at the stake and charged with heresy and cross-dressing. From peasant girl to French heroine, to martyr and Catholic saint, Joan inspired countless artistic depictions. Her image navigated masculinity and femininity from her disguise as a boy in enemy territory, to her wearing of armour while revealing her true identity. Her image and gender expression fluctuated to fit each artist's unique perception of Joan.

In the nineteenth century, romanticised visions of the Middle Ages led to new interpretations of Joan. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Joan of Arc (1882) showed her contorted in a prayer-like gesture while clutching her sword.

There is no emphasis on her credibility as a warrior or leader. Instead, she becomes, like Judith and Salome, a feminine and sensual figure.

This depiction by John Gilbert shows her in the heat of battle, while still presenting her as conventionally feminine.

Later, representations of Joan were found in theatrical productions as well as paintings. Gilbert Anthony Pownall's 1924 portrait of Alice Maud Mary Arcliffe as Joan of Arc renders her as a powerful, androgynous figure.

Similarly, Anthony Devas' 1955 portrait of Dorothy Tutin as Joan of Arc in 'The Lark' is pared down and devoid of armour or swords. Instead, the focus is centred on Joan's uncompromising gaze. She comes across as a headstrong modern woman, reflecting shifting attitudes to femininity. Devas' portrayal of Joan of Arc also foreshadowed the arrival of Otto Preminger's 1957 film Saint Joan, starring Jean Seberg sporting androgynous, cropped hair.

Dorothy Tutin as Joan of Arc in 'The Lark'

c.1955

Anthony Devas (1911–1958)

In 1909, the Parisian hairdresser Antoine Cierplikowski had drawn inspiration from Joan's cropped hair to create the fashionable bob cut. Cropped hair for women become the iconic hairstyle of the 1920s and was associated with the new 'modern' and liberated woman. It also became a way for women loving women to identify one another. This queer coded language would include suits and monocles, reclaiming traditionally masculine fashion. A feminist and queered reclaiming and reinterpretation of Joan of Arc?

When we consider historical representations of women with swords, the male gaze weaves in and out of many of these depictions.

Yet when these images are created by or for women, a more complex picture begins to emerge. This art historical tradition has paved the way for representations of women wielding swords today – cutting a victorious path through pop culture. Their past and current destruction of gender and sexual norms are not only accepted, but celebrated and interpreted in new ways.

For example, the sword-wielding She-Ra was created in the 1980s as an alternative to He-Man. Now, she has been reclaimed even further as a complex and multifaceted queer icon in Netflix's recent reboot led by queer creator Noelle Stevenson.

Historic depictions of fighting, weaponised women show us that a woman's power does not have to measure up to a traditional male heroic standard. The way the Amazons, Judith, Joan of Arc and Salome can be revisited and reinterpreted shows us another story, one in which women can define their femininity, gender non-conformity, and power on their own terms – with or without a sword.

Claire Mead, art and design curator