by Mitja Kolsek, the 0patch Team

Introduction

Two weeks ago SensePost's Etienne Stalmans and Saif-Allah El-Sherei published an interesting analysis of a Microsoft Office feature that can be easily exploited for running arbitrary code on user's computer. In the next few days, Cisco Talos reported of detected in-the-wild attacks exploiting this very issue, while SANS reported it being exploited by Necurs and Hancitor malware campaigns. Endgame's Bill Finlayson and Jared Day subsequently wrote an excellent root-cause analysis of this issue.

The feature in question is called Dynamic Data Exchange, introduced in early Windows systems but still used in many places today. For instance, if you want to see the revenue value from a specific cell in your financial statement Excel worksheet mirrored in a Word document - so that updating the worksheet reflects itself in Word, you can use DDE for that. The field that does that would look like this:

{ DDEAUTO Excel "statement.xlsx" revenue }

The "AUTO" in DDEAUTO instructs Word to automatically use DDE for updating the external value when the document is opened. Instead of DDEAUTO, one can use DDE, but it will require the user to manually trigger updating of the value.

The documentation on DDEAUTO and DDE fields describes their behavior, including that "the application name shall be specified in field-argument-1; this application must be running." But what happens when the application (e.g., Excel from the above example) is not running? This happens:

Word helpfully offers to launch the application for you, which is undoubtedly user-friendly. It is also where a feature turns into a vulnerability: the application name can be a full path to a malicious executable (on USB drive or network) or to a benign executable that will do malicious things based on the arguments it is provided. So when the user agrees to Word launching the DDE application, attackers code gets executed on his computer.

According to SensePost, "Microsoft responded that as suggested it is a feature and no further action will be taken, and will be considered for a next-version candidate bug." Microsoft is full of smart people who try very hard to keep their users secure (we personally know many of these people) and we believe they have good reasons for such decision - or for subsequently reverting it in case that should happen. In case of DDEAUTO (which is the better attack vector), the user has to provide two non-default answers in popup dialogs, so even if these dialogs are not security warnings, some amount of social engineering would certainly be required in an attack. While we're seeing reports of this feature being used by attackers, we currently don't have any data on how successful they are.

Regardless of Microsoft's position on this, both defense and offense sides sprung into action. The former started looking for mitigations and creating signatures and detection rules for blocking attacks, while the latter kept coming up with new attack vectors (Outlook email, Calendar invites) and ideas on how to bypass detection. A fun game to play, no doubt, but we already know that offense will always be winning. Putting guards around the hole can ever only slow the attackers down, as they will always find ways to bypass them. The only definitive way to prevent the hole from being exploited is to close it. In code. And that's what we do.

Analysis

The entire problem seems to stem from Word deviating from the documentation and helpfully attempting to launch the application named in a DDE or DDEAUTO field. This is implemented by calling CreateProcess with the provided application name, which covers two cases:

- If application name is a full path to an executable, such as "C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe", that executable is launched with arguments provided in the DDE/DDEAUTO field;

- If application name is not a full path, such as "Excel", CreateProcess starts looking for it in the system search path, starting with the current working directory, followed by three system folders, and ending with all locations specified in the PATH environment variable.

This has two security-related implications. One can obviously just specify a full-path malicious executable, even from a network path, and have it executed on user's computer. (Note that a network path can be on the Internet behind user's firewall, and Windows with the default-running Windows Client Service will download the executable via HTTP - it will just take longer.)

Less obviously, there is a binary planting potential here: Word sets its current working directory to user's Documents folder upon launching (and let's assume the attacker can't plant his malicious executable there), which is good. However, the user can inadvertently change the current working directory by opening a file via File Open dialog, which happens by default. So an attacker could trick the user to open a Word document from his network share or USB key, which would set Word's current working directory to attacker-controlled location. Subsequently, a DDEAUTO field could launch a malicious executable without providing a full path to it.

We described this second attack vector to explain why simply blocking DDE/DDEAUTO fields that use a full path would not be enough to fully neutralize exploitation. In fact, this shows that even a benign case of {DDEAUTO Excel "statement.xlsx" revenue} in a trusted (even signed!) document could be used to launch malicious Excel.EXE from attacker's location.

DDE-related application launching in Word is apparently pretty dangerous, and we were tempted to put some security around it. But the more we thought about what to do, the more it became clear that it's impossible to distinguish between a malicious and benign use of DDE/DDEAUTO. We could disallow any forward- and back-slashes in the application name, but as shown above, even single-word application names can be misused. We could also change the current working directory to a safe location before CreateProcess gets called (and we actually already had a patch candidate doing that) but what is a universally safe location on millions of differently-configured computers worldwide?

Then we decided to do some functional testing, and discovered that we were unable to get Word (either 2010 or 2013) to properly launch the requested application at all in any meaningful way. For instance, the following did launch Excel (with binary planting concerns aside):

{ DDEAUTO Excel " " }

But that's clearly useless, as no file and range are specified. However, the following, while useful, did not launch Excel. Process Monitor showed a single attempt to launch excel.exe from user's Documents folder (probably because it was the current working directory):

{ DDEAUTO Excel "statement.xlsx" revenue }

In contrast, the above worked great for getting the revenue value from statement.xlsx when the latter was already opened in Excel on the same computer. And that was it. We decided to simply amputate the app-launching capability for the purpose of DDE.

Patching

We located the code block with the CreateProcess call in wwlib.dll, removed the call and simulated a failed CreateProcess call by putting 0 in eax. After creating a patch like this, it turned out that Word still launched the specified application. What was happening? It turned out there is a fallback mechanism in place that tries to launch the app again from mso.dll if CreateProcess in wwlib.dll fails. Word apparently really tries to help the user launch the app.

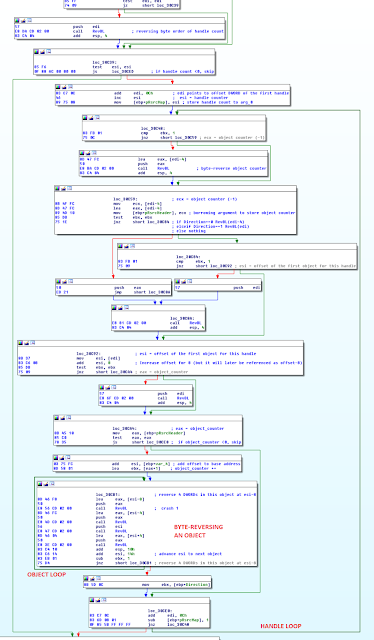

So we also removed the fallback code. The image below shows the relevant code graph, including the CreateProcess and Fallback blocks, which we effectively amputated.

Our first micropatch was for 64-bit Word 2010 with the following source code:

; Patch for WWLIB.DLL_14.0.7189.5001_64bit.dll

MODULE_PATH "C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\Office14\wwlib.dll"

PATCH_ID 294

PATCH_FORMAT_VER 2

VULN_ID 3081

PLATFORM win64

patchlet_start

PATCHLET_ID 1

PATCHLET_TYPE 2

PATCHLET_OFFSET 0x92458c ; at the beginning of the CreateProcess block

JUMPOVERBYTES 68 ; jump over everything including CreateProcess call

code_start

mov eax, 0 ; we say that CreateProcess failed to prevent original code

; from tryig to close the handle of the non-existent process

code_end

patchlet_end

patchlet_start

PATCHLET_ID 2

PATCHLET_TYPE 2

PATCHLET_OFFSET 0x92463f ; at the beginning of the fallback block

JUMPOVERBYTES 40 ; remove the entire block

N_ORIGINALBYTES 5

code_start

nop ; no added code here, we just need to remove the original code

code_end

patchlet_end

MODULE_PATH "C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\Office14\wwlib.dll"

PATCH_ID 294

PATCH_FORMAT_VER 2

VULN_ID 3081

PLATFORM win64

patchlet_start

PATCHLET_ID 1

PATCHLET_TYPE 2

PATCHLET_OFFSET 0x92458c ; at the beginning of the CreateProcess block

JUMPOVERBYTES 68 ; jump over everything including CreateProcess call

code_start

mov eax, 0 ; we say that CreateProcess failed to prevent original code

; from tryig to close the handle of the non-existent process

code_end

patchlet_end

patchlet_start

PATCHLET_ID 2

PATCHLET_TYPE 2

PATCHLET_OFFSET 0x92463f ; at the beginning of the fallback block

JUMPOVERBYTES 40 ; remove the entire block

N_ORIGINALBYTES 5

code_start

nop ; no added code here, we just need to remove the original code

code_end

patchlet_end

After applying this micropatch, Word no longer attempts to launch the application specified in DDE and DDEAUTO fields. The dialogs remain the same, and Word still asks if your want to launch the application - but even if you agree, the application doesn't get launched and Word proceeds as if the attempt to launch it has failed (notifying you that it cannot obtain DDE data).

Demonstration

Conclusion

We created micropatches for Office 2007, 2010 ,2013, 2016 and 365 (32-bit and 64-bit builds). To have micropatches applied, all you need to do is download, install and register our free 0patch Agent. (Glitch warning: due to being sandboxed in Word 2016 and 365, 0patch Console either shows an empty line for Word in the Applications list with only the on/off button, or doesn't show Word at all. While said button works as it should, it looks confusing. We're working on fixing this by end of our beta.)

Note that we only make micropatches for fully updated systems, so make sure to have your Office updated (latest service pack plus all subsequent updates from Microsoft) if you want to use them. We'll be tweeting out notifications about additional micropatches so follow us on Twitter if you're interested.

Our micropatch can co-exist with existing mitigations for this same issue, so you can still disable automatic updating of DDE fields (either manually, or using Will Dormann's collection of Registry settings for various Office versions) and use malware detection/protection mechanisms - although the latter will add no value once the hole has been closed.

If active exploitation of this feature continues to spread, Microsoft will likely respond with an update or mitigations. When they do, make sure to apply them - as the original vendor they know their code best, and they are also aware of many use cases none of us could think of.

Should you experience any problems with our micropatches, please let us know. It's unlikely that our injected code would be flawed (being a single CPU instruction), but you may have a DDE use case that doesn't agree with our solution. Send us an email to support@0patch.com if you do. One great thing about micropatches is that in addition to getting applied in-memory while applications are running, they can also get revoked in-memory. So we can revoke a micropatch and issue a better version without your users even knowing that anything happened. Zero user disturbance.

Finally, let's quickly rehash the benefits of micropatching:

- A micropatch, just like original vendor's update, actually closes the hole instead of putting guards (signature-based detection or prevention) on attacker's paths towards the hole.

- In contrast to typical vendor updates, which replaces a huge chunk of a product, a micropatch brings a minuscule change to the code on the computer. This means minimal possible risk of error, as well as ability for everyone to actually review the new code (anyone familiar with assembly language can quickly understand the source code above).

- A micropatch gets instantly applied in memory, even while the vulnerable application is running, so the user doesn't have to restart the application or even reboot the computer.

- If something is wrong with a micropatch (while the risk is minimal, it's still there), it can be just as instantly removed from running applications, and replaced with a corrected one. Again, users don't even notice anything. (You want them to focus on their work, not on security updates, don't you?)

- With the low risk of error and the ability to quickly apply and un-apply micropatches, you can afford to simplify your updating process. Except in the most critical of cases, you don't need to test a micropatch for weeks or months before applying it, as the cost of un-applying is approximately zero if you can do that from a central location (we're currently working on that, by the way). In comparison, what was your cost of un-applying a "fat update" from thousands of computers the last time something went wrong with an update?

Keep your feedback coming! Thank you!

[Update 3/11/2017: Windows 10 introduced a new mitigation called Attack Surface Reduction with the Fall Creators Update. We took a look at how it helps block DDE-borne attacks and how it compares to our micropatches.]