Why “Freakonomics” failed to transform economics

The approach was fun, but has fallen out of favour

“Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.” So starts Alfred Marshall’s “Principles of Economics”, a 19th-century textbook that helped create the common language economists still use today. Marshall’s contention that economics studies the “ordinary” was not a dig, but a statement of intent. The discipline was to take seriously some of the most urgent questions in human life. How do I pay my bills? What do I do for a living? What happens if I get sick? Will I ever be able to retire?

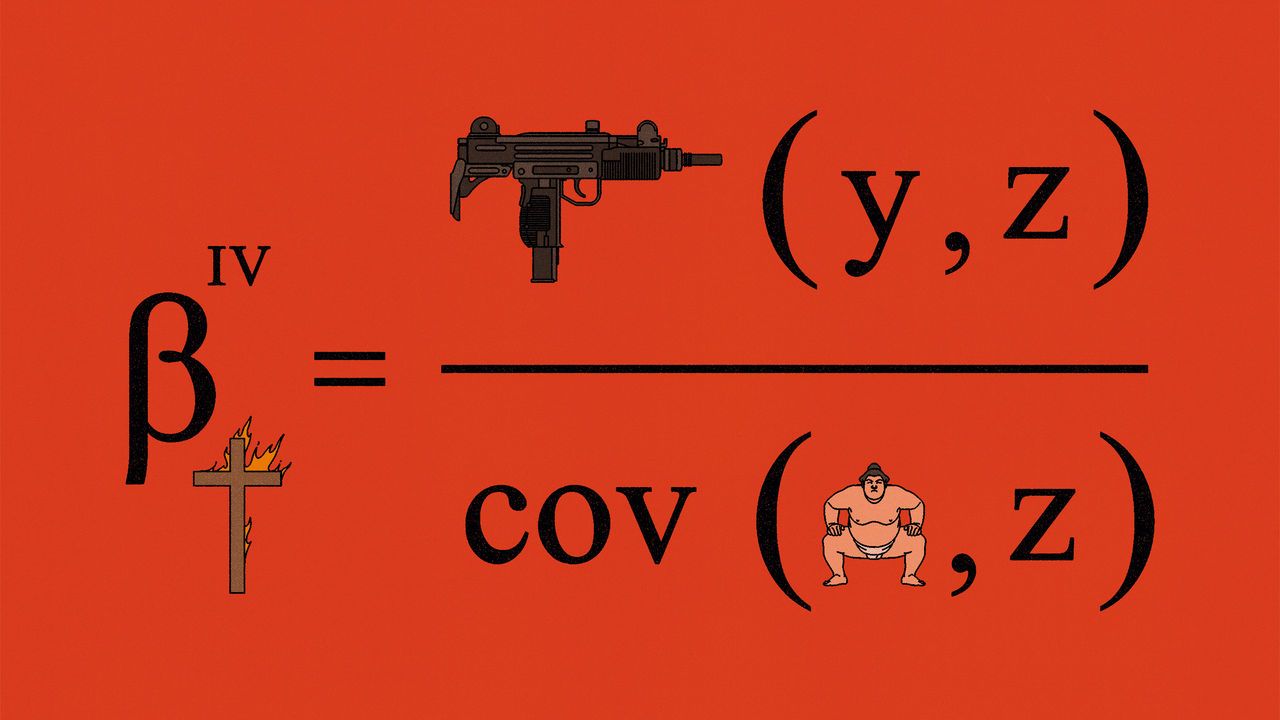

In 2003 the New York Times published a profile of Steven Levitt, an economist at the University of Chicago, in which he expressed a very different perspective: “In Levitt’s view,” the article read, “economics is a science with excellent tools for gaining answers but a serious shortage of interesting questions.” Mr Levitt and the article’s author, Stephen Dubner, would go on to write “Freakonomics” together. In their book there was little about the ordinary business of life. Through vignettes featuring cheating sumo wrestlers, minimum-wage-earning crack dealers and the Ku Klux Klan, a white-supremacist organisation, the authors explored how people respond to incentives and how the use of novel data can uncover what is really driving their behaviour.

Freakonomics was a hit. It ranked just below Harry Potter in the bestseller lists. Much like Marvel comics, it spawned an expanded universe: New York Times columns, podcasts and sequels, as well as imitators and critics, determined to tear down its arguments. It was at the apex of a wave of books that promised a quirky—yet rigorous—analysis of things that the conventional wisdom had missed. On March 7th Mr Levitt, who for many people became the image of an economist, announced his retirement from academia. “It’s the wrong place for me to be,” he said.

Explore more

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the headline “Gang warfare”

Finance & economics March 23rd 2024

- How China, Russia and Iran are forging closer ties

- Japan ends the world’s greatest monetary-policy experiment

- Why America can’t escape inflation worries

- First Steven Mnuchin bought into NYCB, now he wants TikTok

- America’s realtor racket is alive and kicking

- How to trade an election

- Why “Freakonomics” failed to transform economics

More from Finance and economics

Xi Jinping really is unshakeably committed to the private sector

He balances that with being unshakeably committed to state-owned enterprises, too

The dangerous rise of pension nationalism

Pursuing domestic investment at the expense of returns is reckless

Europe prepares for a mighty trade war

Will it be able to stick to its rule-abiding principles?