Architecture

Architecture [архітектура; arkhitektura]. Ukrainian architecture has a rich history and occupies an important place in the history of European art. Extant architectural monuments testify to the high state of the art in Ukraine. They display originality, functionality of construction, and attentiveness to form. While assimilating the engineering and artistic principles of antiquity, old Ukrainian builders refined them and supplemented them with local characteristics; at the same time they influenced and enriched the architecture of neighboring countries.

The prehistoric and early period. Architectural constructions in Ukraine date back to the Paleolithic Period. By the end of the Neolithic Period (5000–3000 BC) the Trypillia culture had developed among the tribes inhabiting Right-Bank Ukraine. In the 1st millenium BC Greek colonies (eg Olbia, Teodosiia, Chersonese Taurica, Panticapaeum) appeared on the coast of the Black Sea (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast). Their buildings were constructed according to Greek style and were enriched by vaults of wedged stone, which were unknown in Greece itself. In the 6th–3rd century BC many fortified settlements were built by the Scythian tribes. The ruins of the Scythian capital, Neapolis, near Simferopol have been well preserved to this day. The indigenous population in the Crimea built cave settlements such as Eski-Kermen, Manhup, and Chufut-Kaleh. Stone cult figures, or megaliths, on Mount Kishka near Simeiz in the Crimea and in the lower Dnipro River region were erected in the 1st millennium AD. As Christian religious architecture evolved, stone building, based on the Greek-cross form, the principal form of Byzantine church architecture, developed on the ruins of the Greek colonies. Excavations have also uncovered ground plans of rotundas and Roman-type basilicas, fortifications such as the Kharaks fort, and other structures.

The Princely Era. Byzantine culture flourished under the Macedonian dynasty (867–1057). During this period the Kyivan state adopted Byzantine Christianity and its rich architectural traditions. Drawing on their own tradition of wooden folk architecture and on certain Western influences, the architects of Kyivan Rus’ adapted the Old Christian and Byzantine styles to local conditions and created their own synthesis. This original and creative interpretation permits one to speak of a Ukrainian style.

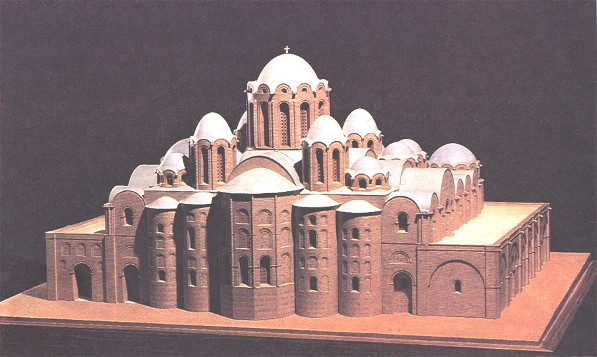

The Kyivan grand prince Volodymyr the Great built the first famous stone church—the Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God, or the Church of the Tithes (989–96). Only its foundations have survived, but its plan and construction were repeated in a host of churches in Kyivan Rus’. Under Yaroslav the Wise Kyiv became one of the important capitals of Europe. The prince encircled the city with defensive walls. Of the three city gates only the remains of the Golden Gate, which was topped by the Church of the Annunciation, have been partly preserved. The masterpiece of the Princely era is, however, the Saint Sophia Cathedral (1037–54). The original structure was a monumental, rectangular temple with five naves and five apses on the eastern side; its prototype was the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. It had a balcony on three sides and was topped by thirteen cupolas in a pyramidal arrangement. Of the many palaces built in the 11th–12th century only the foundations remain, but many Kyivan churches and monasteries from the period survived until the mid-1930s (when many of them were demolished by the Soviet authorities). The more important among them were the Cathedral of Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery (1108, destroyed in 1934); the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1078, destroyed in 1941); Saint Michael's Church of the Vydubychi Monastery (1088); the Holy Trinity Church built above the gate of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1108); Transfiguration Church in Berestove (a Kyiv suburb, mid-11th century); the Pyrohoshcha Church of the Mother of God (1136, destroyed in 1935); the Church of Saint Cyril's Monastery (1146); and the Church of the Three Saints (1183, destroyed in 1935).

Chernihiv ranks second in the number of churches preserved from the Princely era: the Cathedral of the Transfiguration (1036); the Cathedral of the Yeletskyi Dormition Monastery (12th century); Saints Borys and Hlib Cathedral (12th century); Saint Elijah's Church (12th century); and the Church of Good Friday (early 13th century). The most important churches that have been preserved (and partly reconstructed) in other towns are Saint Basil's Church (late 12th century) in Ovruch; the Dormition Cathedral in Volodymyr (1160); Saint George's (Dormition) Cathedral in Kaniv (1144); and Saint Panteleimon's Church (pre-1200) in princely Halych (which survives in its original state with a carved Romanesque portal of great artistic value). Excavations of princely Halych in 1935–7 uncovered the foundations of the majestic Cathedral of the Dormition built by Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl at the site of the princely residence in Krylos. Only fragments, such as the foundations or details of the capitals, remain of the magnificent churches built by King Danylo Romanovych in Kholm and Peremyshl (eg, Saint John's Cathedral of the 12th century).

After the Mongol-Tatar invasion (second half of the 13th to the 16th century). After the Tatar invasion construction was restricted to small buildings, and these were built mostly in the western territories (known as the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia until the middle of the 14th century). Some castles and a few fortified churches have been preserved from this turbulent period. The foundations of the castle-fortresses varied, depending on the terrain. Their towers, turrets, galleries, and parapets were of a monumental, severe appearance. The best examples of medieval castles are located in Zinkiv (Khmelnytskyi oblast) in Podilia, Sataniv on the Zbruch River, Lutsk, Terebovlia, Zbarazh, Kremenets, and Khotyn. The imposing fortress in Kamianets-Podilskyi (15th–16th century) was reconstructed beginning in the 17th century. Church building adhered to the style of the Princely era and was influenced by the tradition of wooden architecture. An outstanding example of this is the church-fortress of the Holy Protectress (1467) in Sutkivtsi, Podilia. Like many other buildings of the time it was designed for defense. The wooden belfries, which have often preserved their archaic forms, probably served as models for gate towers. As time passed, the master builders made them ever more elaborate. The finest examples of wooden belfries are located in Galicia: Potylych (Potelych), Drohobych, Yamna, Mykulychyn, Tysmenytsia, Topilnytsia, Yasenytsia Zamkova, and Turka.

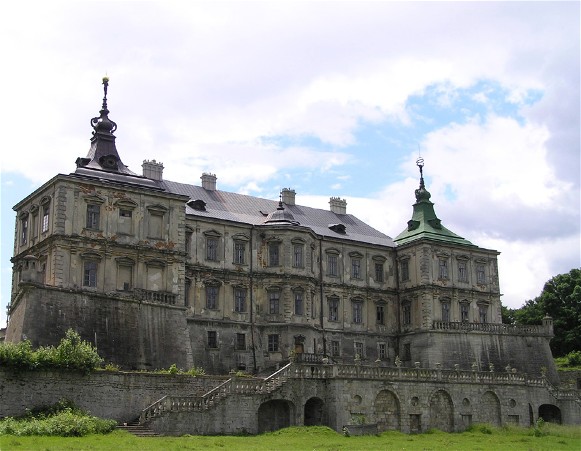

The Renaissance. The Renaissance style of architecture was adapted to the Byzantine-Ukrainian heritage and to the Ukrainian character. The style developed mainly in towns that were built on the Western European pattern. Italian and then German, French, and native architects constructed new churches and private and municipal buildings and reconstructed castle-fortresses, finishing them in the new style. The castles in Ostroh, Stare Selo near Lviv, Buchach, Olesko, and Kamianets-Podilskyi acquired picturesque attics. Castle-palaces like the one in Pidhirtsi (1636–40) in Galicia, which was influenced by French palace architecture (Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan and A. de l'Aqua), are good examples of this style. The best examples of Renaissance architecture are found in Lviv. Most of them were built by masters of Italian origin, such as Paolo Romanus, Amvrosii Prykhylny, and Voitykh Kapynos. They created the architectural masterpieces of the Renaissance period: the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood's Dormition Church in Lviv, also known as the Wallachian Church (1598–1631, by P. Romanus); its Korniakt Tower (1578, by Pietro di Barbone); and the Lviv brotherhood's Chapel of the Three Saints (1590–1671). The Black Building, the Korniakt building, and the chapel-mausoleum of the Kampian family (1619) on the outside wall of the Latin Cathedral deserve mention.

The Crimea. The architecture of the Crimea is unique and complex. It was tied to the traditions of the local population, which descended from the Taurians, Scythians, Sarmatians, and other tribes, and later from the Italian traders and colonists. Genoese fortresses in Sudak, Teodosiia, and Balaklava, Armenian monasteries and churches (eg in Surb-Khach near Staryi Krym), and Tatar mosques (eg, in Yevpatoriia in 1552 by Koca Sinan) were built in this period. The main architectural monument is the Crimean khan's palace in Bakhchysarai (16th–18th century).

The baroque period. The architecture of the late Renaissance displayed certain features of the early baroque: dynamism, spiral lines, mannerisms, decorativeness. The Boim family chapel (1609–11) and the Church of Good Friday in Lviv are examples of the late Renaissance, while the church built by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky in Subotiv (1653), with its imposing front, already belongs to the early baroque. The baroque was an expression of 17th- and 18th-century European culture. Its vigorous growth in Ukraine marked a golden age of the arts, similar to that of the Princely era. The center of artistic life shifted again to the Dnipro River region, dominated by Kyiv, and the new patrons were Hetman Ivan Mazepa, who built four churches and restored about twenty, and the Cossack starshyna officers. The synthesis of West European baroque and Byzantine-Ukrainian tradition produced an original fusion of the three-nave, Greek-cross church with the basilica. Having elaborate decorative elements, which were often borrowed from wooden architecture, this style was spontaneously called the ‘Cossack baroque’or the ‘Mazepa baroque.’ Because it was a truly original adaptation of the baroque, this style is generally called the ‘Ukrainian baroque.’

The best evidence for the adaptation of the baroque can be found in the princely churches that were reconstructed mostly under Metropolitan Petro Mohyla—Saint Sophia Cathedral, the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, and the churches of Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery and Vydubychi Monastery. Their principal feature was the form and rchitectural composition of the gilded cupolas. The general appearance of a city was often defined by its monasteries, which included many secular buildings, such as the metropolitan's residence at the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (1758); the regimental chancellery in Chernihiv (1680–90, reconstructed in 1758); and the residence of Vasyl Kochubei in Baturyn. In the 18th century the typical church was cruciform; this was the second peculiarity of the Ukrainian baroque. Three-domed and five-domed structures, built on a central plan borrowed from the wooden churches of Ukraine, represent the highest achievement in artistic expression and purity of form. The following are examples of such churches: the 12th-century Transfiguration Church in Berestove (in Kyiv), reconstructed in 1638–43; the Cathedral of the Holy Protectress in Kharkiv (1689); Saint George's Church of the Vydubychi Monastery (1696); the Church of All Saints above the Economic Gate of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1696–8); the cathedral of the Mhar Transfiguration Monastery near Lubny (1684–92, built by Johann Baptist and M. Tomashevsky); and the church of the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood Monastery (1693) and Saint Nicholas's Military Cathedral (1690–3) in Kyiv, both funded by Hetman Ivan Mazepa and destroyed in the 1930s.

Wooden architecture. Wooden churches in Ukraine deserve particular attention because of their beautiful contours, proportions, and functionality. The oldest preserved churches (16th–17th century) are mostly in the Carpathian Mountains, particularly in the Boiko region. The church in Trochany (Tročany) in Transcarpathia is an example of the oldest style. The tripartite (or three-frame) construction, in which each frame is topped by a tiered pyramidal roof, is typical of Ukrainian architecture. The Boiko style of building progressed from the two-tiered top, as found in the churches in Topilnytsia, Lenytsia, Potelych, and Drohobych, to three-tiered and four-tiered tops, as in the churches in Borynia near Turka, in Studene, Vyzhnie, and elsewhere. Churches of seven stories are located in Kryvka (moved to Lviv in 1930), Vysotske, Vyzhnia, Matkiv, Rosokhach, and Komarnyky. While they share certain common features, the various schools of Ukrainian wooden architecture have their peculiar traits. Thus, Saint Nicholas's Church in Kryvka (1763) is characteristic of the Boiko school; Saint Nicholas's Church in Chernivtsi (1607) and the church in Poliana (1648) in Bukovyna—of the Bukovynian school; the churches in Vorokhta, Kosmach, and Nadvirna (all of the 18th century)—of the Hutsul school; the church in Steblivka (1643)—of the Lemko school; the churches in Mukachevo (1777) and Kanora (18th century) in Transcarpathia—of the Transcarpathian school; the church in Zhovkva (1705)—of the Galician school; the church in Rozvazh (1782) in Volhynia—of the Volhynian school; and the churches in Korsavary (1799) in Podilia and Kamianets-Podilskyi—of the Podilian school. The Trinity Cathedral in Novoselytsia (Novomoskovsk) (1773–8, by Yakym Pohrebniak) belongs to the Dnipro region school and is a wonder of Ukrainian wooden architecture, having nine frames with nine cupolas and a height of 65 m.

The Ukrainian builders of baroque wooden churches strived to create an impression of great inner height. Modern architects and engineers believe that the wooden constructions of this period, which approached 50 m in height, attained the limits of the medium's possibilities and are unique in world architecture. To create the illusion of height the walls were inclined inwardly, and each higher tier was made narrower than the one below. The best examples of the Cossack baroque were the churches in Pakul (1710), Novi Mlyny (mid-18th century), Berezna (1759), Artemivka (1761), Verkhnii Byshkin (1772), and Chervonyi Oskil (1779). All these churches were destroyed by the Soviets.

Jewish synagogues, which were built by Ukrainian masters as well, deserve special mention. Some of the best examples of this type of architecture have been preserved in Ukraine. Among them are the synagogues in Zabłudów (16th century), Brody, Pechenizhyn, Rozdil, Zhydachiv, Khodoriv, and Kaminka-Strumylova (now Kamianka-Buzka). Secular town architecture, consisting of town halls, inns, taverns, and burghers' residences possessed such elements of folk architecture as porches, vestibules, many-layered roofs, and richly carved columns.

Rococo. In the mid-18th century the influences of a more decorative style—the rococo—made themselves felt. Colorful examples of this style are Saint George's Cathedral in Lviv (1744–64, built by Bernard Meretyn (Merderer), the town hall of Buchach (1751), and Saint Andrew's Church in Kyiv (1747–53, designed by Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli). Among the last rococo examples are the belfries of Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery and of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, both ornamented with floral motifs in stucco, and the famous belfry of the Kyivan Cave Monastery by Johann Gottfried Schädel (1731–45).

Classicism. The calmness and coldness of classicism replaced the restlessness of the baroque in the form of the official Empire style. City planning reflected classicism in its geometric, regular street layout, symmetric arrangement of buildings, and an orderly reconstruction of old cities such as Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Poltava. After the Turks had been expelled from the Black Sea region and the Crimea, the towns of Kherson, Mariupol, Mykolaiv, Odesa, Sevastopol, etc developed rapidly. Many industrial buildings (a wooden cloth and silk factory in Katerynoslav), municipal buildings (the city hall in Mykolaiv), and educational institutions (Nizhyn Lyceum, Kyiv University [1803, by Andrei Melensky], Odesa University [1804–9, by Thomas de Thomon]) were erected in the new style. Some famous classical constructions were built in Poltava and Odesa: the Prymorskyi Boulevard, Vorontsov palace, the Potemkin steps in 1841 by Francesco Boffo. The finest examples of classicism are the palaces of Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky in Pochep (1796) and Baturyn (1799, by Charles Cameron), the palace of Petro Zavadovsky in Lialychi (1794, by Giacomo Quarenghi), the Galagan palace in Sokyryntsi (1829, by P. Dubrovsky); the Oleksandriia Dendrological Park in Bila Tserkva, the Sofiivka Park in Uman, and the Vorontsov palace and park in Alupka. Most of the architects were foreigners; hence their work rarely bore any relation to Ukrainian architectural traditions.

More churches built in the Empire style have been preserved in the Kharkiv and Poltava regions than elsewhere. Usually they have a central plan, like the cathedral in Khorol (1800) and the belfry (1844) of the Kharkiv Dormition Cathedral. Urban architecture, particularly the city halls in Kharkiv, Poltava, Kyiv, and Lviv (1827–35, by J. Markl and F. Tresther), reflected this style. Architecture, which reflected the utilitarianism and commercialism of its times, became influenced increasingly by an official standard. By the end of the century it developed according to the then-fashionable European eclectic diversity of styles. Examples of eclecticism are the Gothic Catholic church in Kyiv (1897–1900, by Vladyslav Horodetsky); the residence of the metropolitan of Bukovyna, now Chernivtsi National University (1864–82, by J. Hlavka); the pseudo-Byzantine Saint Volodymyr's Cathedral in Kyiv (1862–82, by Aleksandr Beretti); and the Trinity Cathedral in Pochaiv (1906, by Aleksei Shchusev, built in the Old-Rus’ style).

Revival of a Ukrainian style (Ukrainian modern). At the beginning of the 20th century, as the Ukrainian national movement grew in strength, artists sought to revive a Ukrainian style. Vasyl H. Krychevsky became the pioneer and champion of this trend. His first successful work in this style was the Poltava gubernia zemstvo building (1905–9), later the Poltava Regional Studies Museum, which gave rise to many imitations and variations. Among the prerevolutionary architectural experiments the most remarkable were the Pedagogical Museum (1911–13, by Pavlo Aloshyn), now the Teachers’ Building; the Public Library (1914–29, by Vasyl Osmak), now the National Library of Ukraine; and the tsar's palace in Livadiia in the Crimea (1910–11, by N. Krasnov). In 1918 the Society of Ukrainian Architects and Kyiv Architecture Institute were established in Kyiv through the initiative of such Ukrainian architects as Dmytro Diachenko, Vasyl H. Krychevsky, Volodymyr Sichynsky, M. Kravchuk, and Oleksander Verbytsky. Using baroque motifs and elements of wooden folk architecture, Ukrainian architects managed to create a fresh synthesis and built many structures in the new style. In the 1920s and 1930s P. Holovchenko, K. Kunytsia, Petro H. Yurchenko, and others continued to develop the national style and designed workers' settlements, collective-farm clubs, etc. Many of them were accused later of propagating a ‘national style’ and persecuted.

The Soviet period. During the time of industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture (1925–32), many new cities and giant industrial complexes were built: New Zaporizhia and the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station (1927–32, by architects V. Vesnin, N. Colli, and S. Andriievsky); the settlement of the Kharkiv Tractor Plant (1931–3, by Pavlo Aloshyn); etc. The most important of the public and industrial buildings were the Derzhprom (State Industry) complex in Kharkiv built in the constructivist style by S. Kravets and S. Serafimov, the Railroad Workers' Palace of Culture in Kharkiv (1928–32, by O. Dmytriiev) and the Kyiv Artistic Film Studio (1927–30, by Valerian Rykov). These large projects were usually entrusted to architects from Russia.

The search for new ideas in architecture provoked wide discussion. Even the most functional and constructivist tendencies, which were prompted by faith in technology and expressed the spirit of the times, were criticized. The architects of 1934–41 turned mostly to the classical heritage and created on its basis a pompous Stalinist style. The new style combined elements of the Saint Petersburg Empire style with a historical eclecticism and an inclination towards pseudomonumentalism. Examples of this style are the building of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (1936–9, by Volodymyr Zabolotny and N. Chmutina); the Trade Institute in Kyiv, by Dmytro Diachenko; and the building complex of the Commercial Academy in Kyiv, by Ye. Nakonechny, S. Hrabovsky, and S. Liuba.

Much was expected of the new Academy of Architecture of the Ukrainian SSR in Kyiv (1945), renamed in 1956 the Academy of Construction and Architecture of the Ukrainian SSR, directed by Volodymyr Zabolotny. In the postwar reconstruction of Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities, the Stalinist eclecticism was particularly evident. The principal boulevard of Kyiv, Khreshchatyk, was rebuilt in this manner by the architects Aleksandr Vlasov, Borys Pryimak, V. Zabolotny, Anatolii Dobrovolsky, and others. The style was abandoned in 1955, but modernization and the application of Western architectural ideas in Ukraine began only in the 1960s, owing partly to younger, postwar architects.

The finer buildings of the Soviet period are the huge sports stadiums in Kyiv—Dynamo (for 30,000 spectators, 1934–6, by Vasyl Osmak and V. Bespaly) and the Sports Palace (for 100,000 spectators, 1958–60, by Mykhailo Hrechyna, Aleksei Zavarov, and V. Repiakh); the sanatoriums in the Crimea—Chornomore in Yalta, Sea Pioneer Camp in Artek (1961, by A. Poliansky and D. Vitukhin); the hotel Tarasova Hora in Kaniv (1961, by O. Husieva, A. Zubok, N. Chmutina, and Viktor Yelizarov); the stations and surface buildings of the Kyiv subway (1960–8); and the concert and film hall Ukraina in Kharkiv (1963, by V. Vasilev, Yu. Plaksiev, and V. Reusov). The outstanding buildings of the late Soviet period were the Kyiv Pioneers' and School Children's Palace (1965–7, by Avram Myletsky and E. Bilsky) and the airport in Boryspil (1961–5, by Anatoly Dobrovolsky, O. Malynovsky, and D. Popenko), which was based on contemporary American reinforced steel-and-concrete construction. During that time many buildings, particularly schools, day-care centers, cinemas, restaurants, and clubs, were decorated with murals, mosaics, and sculpture. Architects paid more attention than before to the building's relation to its surroundings and to the requirements of urban planning.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shukhevych, V. Hutsul’shchyna, vols 1–2 (Lviv 1899–1900)

Hrushevs’kyi, M. ‘Ukraïns’ke mystetstvo,’ in his Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy, vols 3–4 (Lviv 1900–7)

Shcherbakivs’kyi, V. ‘Derev'iani tserkvy na Ukraïni i ïkh typy,’ ZNTSh, no. 74 (1906)

———. Ukraïns’ke mystetstvo (Lviv–Vienna 1913)

Antonovych, D. ‘Rozvii form ukraïns’koï derevlianoï tserkvy,’ Zbirnyk Ukraïns’koho istorychno-filolohichnoho tovarystva, 1 (Prague1925)

Zaloziecky, W. Gotische und barocke Holzkirchen in den Karpathenländern (Vienna 1926)

Buxton, D.R. Russian Mediaeval Architecture (Cambridge 1934)

Dragan, M. Ukraïns’ki derev’iani tserkvy, 1–2 (Lviv 1937)

Sičynskyj, V. Dřevěné stavby v Karpatské oblasti (Prague 1940)

Hordynskyj, S. ‘Ukrainian Architecture,’ UQ, 1948, no. 4

Arkhitektura Ukrainskoi SSR (Moscow 1954)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva: Arkhitektura, 1–2 (New York 1956)

Narysy istoriï arkhitektury Ukraïns’koï RSR, 2 vols (Kyiv 1957–62)

Ukraïna: Arkhitektura mist i sil. Al’bom (Kyiv 1959)

Logvin, G. Ukrainskoe iskusstvo X-XVIII vv. (Moscow 1963)

Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva, 6 vols (Kyiv 1966–70)

Lohvyn, H. Po Ukraïni (Kyiv 1968)

Asieiev, Iu. Arkhitektura Kyïvs’koï Rusi (Kyiv 1969)

Hordyns’kyi, S. Ukraïns'ki tserkvy v Pol’shchi (Rome 1969)

Iurchenko, P. Derev'iana arkhitektura Ukraïny (Kyiv 1970)

Holovko, H. (ed). Suchasna arkhitektura Radians’koï Ukraïny (Kyiv 1974)

Karmazyn-Kakovs’kyi, V. Mystetstvo lemkivs’koï tserkvy (Rome 1975)

Taranushenko, S. Monumental’na derev’iana arkhitektura Livoberezhnoï Ukraïny (Kyiv 1976)

Samoilovich, V. Narodnoe arkhitekturnoe tvorchestvo (Kyiv 1977)

Volodymyr Hodys, Vadym Pavlovsky, Volodymyr Sichynsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20Cathedral.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)