The fall line is a geological boundary, about twenty miles wide, running northeast across Georgia from Columbus to Augusta. It is a gently sloping region that rapidly loses elevation from the north to the south, thereby creating a series of waterfalls. During the Mesozoic Era (251-65.5 million years ago), the fall line was the shoreline of the Atlantic Ocean; today it separates Upper Coastal Plain sedimentary rocks to the south from Piedmont crystalline rocks to the north. The fall line’s geology is also notable for its impact on early transportation in Georgia and consequently on the state’s commercial and urban development

Natural History and Geology

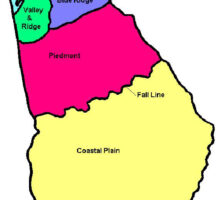

Rivers that flow across the fall line create waterfalls or rapids, which give the “fall line” its name. The geologic regions to the north of the fall line include the Appalachian Plateau, the Valley and Ridge, the Blue Ridge, and the Piedmont. The Upper Coastal Plain and Lower Coastal Plain regions occur south of the fall line.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The geological differences to the north and south of the fall line give rise to variations in soil types, hydrology (water cycles), and stream morphology. For example, sandy soils predominate to the south of the fall line, and wide floodplains have developed along many of the streams in this region. To the north of the fall line, clay soils and narrower stream valleys are the rule. One significant consequence of these differences is that the fall line separates distinctive plant and animal communities. Wiregrass–longleaf pine forests, swamp forests, and tidal marshes form the main landscape features south of the fall line. North of the fall line, deciduous hardwood forests, including oaks and hickories, are native to the Piedmont and mountain regions, as are plant communities on granite outcrops. The soil to the south of the fall line, in the Upper Coastal Plain, is better suited to peanut and vegetable cultivation. Agricultural production to the north, in the Piedmont, centered on cotton cultivation in the past but today focuses on such animal products as poultry (including eggs) and beef.

Photograph by Melinda Smith Mullikin, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Animal populations also vary to the north and south of the fall line. While certain animals, such as deer and opossum, occur throughout the state, many animals are found primarily on one side or the other. For example, the fall line is sometimes called the “gnat line,” because the sandy soil on the southern side is better suited for the gnat’s life cycle, making these insects more common in the southern half of the state. Bird populations vary as well, with several species occurring only above certain elevations in the Blue Ridge region. The Appalachian Plateau, Valley and Ridge, and Piedmont share most bird species, numbering around 110, while the Coastal Plain is home to wetland birds and waterfowl not found elsewhere in the state. The Okefenokee Swamp alone is home to 232 bird species.

Photograph by Siddharth Sharma

Mammal species vary widely among the regions as well. To the north of the fall line, the smoky shrew and deer mouse occur only in the Blue Ridge; numerous bat species inhabit the caves of the Valley and Ridge and Appalachian Plateau; and generalist species like chipmunks and gray foxes occupy the Piedmont. Coastal Plain mammals south of the fall line include the round-tailed muskrat in the swamps; marsh rabbits and mink in the tidal marshes; and the North Atlantic right whale, the state marine mammal, in offshore waters. Among amphibians and reptiles, giant salamanders inhabit the Coastal Plain, while numerous woodland salamanders in the Appalachian Mountains give this region the highest salamander diversity in the world. American alligators and sea turtles are found south of the fall line, as are the smallest frog species (little grass frog) and largest snake species (eastern indigo) in the United States.

Economic History

Rivers of the Coastal Plain were a major means of commercial transportation during the 1700s and early 1800s. Cities founded along the fall line, called “fall line cities,” are located at the places where these rivers crossed the fall line, marking the upstream limit of travel. The city of Columbus, for example, was established where the Chattahoochee River crosses the fall line; Macon, Milledgeville, and Augusta are similarly located at the crossings of the Ocmulgee, Oconee, and Savannah rivers, respectively. These cities became important transportation hubs because traders could only travel upstream until they reached the waterfalls of the fall line. At that point they were forced to disembark and reload their cargo on the other side of the falls in order to continue their journeys. Columbus served as the upstream head of navigation for the Chattahoochee, as did Augusta for the Savannah River and Macon for the Ocmulgee River. After the first steamship arrived in 1828, Columbus became a gateway city for cotton. Above the fall line, flatboats and barges moved goods around the state. Below the fall line, steamships had unimpeded access to move goods, mostly cotton, into the Gulf of Mexico.

Photograph by Pamela J. W. Gore

In addition to their importance as transportation hubs, fall line cities were successful because of the presence of water resources. Fall line waterfalls first powered mills and eventually powered hydroelectric dams. The availability of waterpower continued to sustain fall line cities even as railroads surpassed river transportation by the middle of the nineteenth century. Although hydroelectric power only supplies about 2 percent of the energy used by Georgia consumers today, the reservoirs created by hydroelectric dams are still used for recreational and fishing purposes.