Creek Indian society contained an unknown number of leaders in the pre-removal era. Each village had civil, religious, and war chiefs of various ranks. Leaders wielded authority only as long as they could persuade others to agree with their decisions. As a result, leadership positions frequently changed hands.

The most important Creek leader was the mico or village chief. In addition to providing domestic leadership , micos served as diplomatic representatives. They welcomed traders, diplomats, and other sojourners into the village, served as representatives at treaty negotiations, and led warriors into battle. Micos could not coerce their villages into obedience. Instead they used various methods to persuade Creeks to follow their lead. They redistributed scarce resources and daily necessities, demonstrated their bravery in warfare, forged trade relationships, arranged diplomatic alliances, and wielded powerful sacred items. In this way Creek micos demonstrated that they deserved their positions of power.

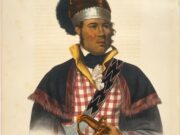

Image from Archives and Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati Libraries

Micos ruled with the assistance of several micalgi or lesser chiefs. They also relied on various advisors and respected village elders, called heniha. Micos and micalagi depended on the heniha to help address many of the daily demands of village life. Heniha used their experiences to offer advice to community leaders. Micos also called upon medicine men to cure sickness, converse with spirits, and practice magic. In addition, a tustunnuggee or ranking warrior played prominent roles in times of warfare, while the yahola officiated various rituals, especially administering the “black drink,” a caffeinated tea-like beverage, primarily made from holly, which was thought to purify those who drank it.

Kinship ties to prominent leaders helped many Creeks obtain power, and as a result the powerful Wind Clan had a disproportionate number of village leaders. Clan leaders, especially elder women, often prevented micos from controlling the most important decisions within Creek society. Clans organized hunts, distributed lands, arranged marriages, and punished lawbreakers. The village power structure, which reserved positions of leadership for members of each of the resident clans, further limited the power of the mico.

Little is known about most Creek Indians, regardless of rank. Only a few entered the historical record as anything more than a name on a treaty. Names like Cussetaw King or Mico Coweta reveal only residence and position of prominence.

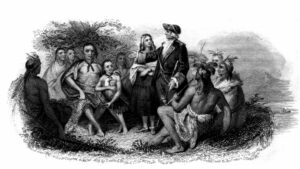

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

One of the earliest exceptions to historical obscurity was Brims, a Coweta village chief. In the early eighteenth century Brims became the most prominent Creek leader; he ensured trade and security for the Creeks by playing European and other Native American powers against one another. In the 1710s he threatened to break off relations with Spain, France, and Great Britain if they grew too demanding or became stingy with gifts or terms of trade. This strategy helped Creeks resist imperial designs on the region and become the region’s power broker. Brims’s power was so great that the Spanish frequently referred to him as the “Coweta emperor.”

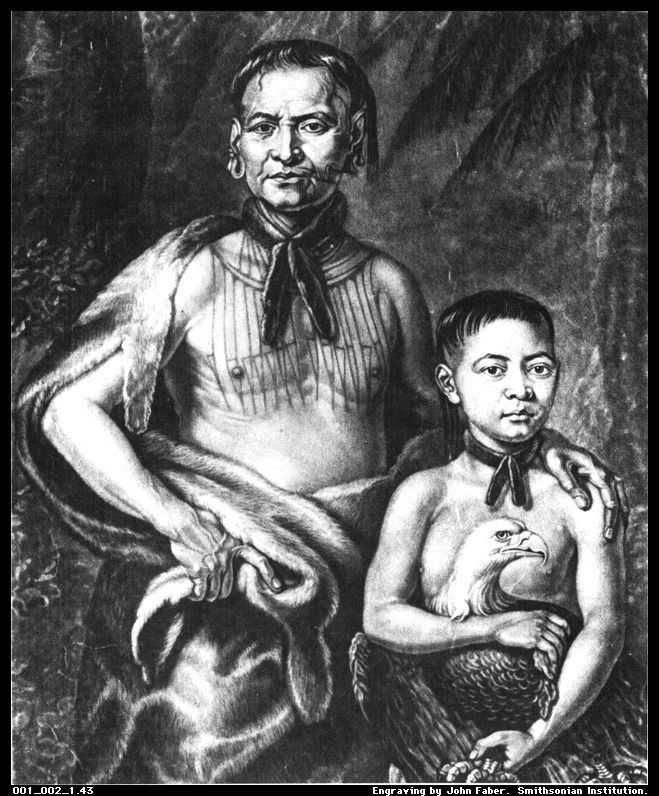

The founding of Georgia increased the opportunities for Creeks to play leadership roles outside of their villages. For example, Tomochichi, who established the Yamacraw village near Savannah around 1730, forged an alliance with General James Oglethorpe. Relying heavily on the assistance of Mary Musgrove, the Creek daughter of a South Carolinian deerskin trader, Tomochichi secured lucrative trade relations for his village. Unlike Brims, Tomochichi failed to use his alliance to stall the expansion of English settlement. Even so, after he moved his village six miles inland in 1736, he maintained diplomatic ties with Oglethorpe and a central role in Creek-Georgia relations.

After Tomochichi’s death many local village leaders emerged, including Malatchi and Chigilli from Coweta and One-Handed King and Handsome Fellow from Okfuskee. Village leaders dominated Creek society until the Revolutionary War (1775-83), when a struggle for tribal leadership occurred. Central to this struggle was Alexander McGillivray, son of a Scottish trader father and a Creek mother. McGillivray, like Brims, used play-off diplomacy to the Creeks’ advantage. McGillivray also tried to centralize decision making and to create forms of coercive power within Creek society. For example, in an attempt to cement his position at the center of the Creek political system, McGillivray signed the Treaty of New York in 1790 on behalf of the “Upper, Middle, and Lower Creek and Seminole composing the Creek nation of Indians.” The treaty ceded a significant tract of Creek hunting grounds to the United States and required the Creeks to turn over fugitives from slavery. In return, the Creeks were given the right to punish non-Indian trespassers in Creek territory. Many Creek leaders resisted these reforms, and the struggle over power turned violent in the Red Stick War (1813-14), part of the larger War of 1812 (1812-15). The Red Stick War ended with the Treaty of Fort Jackson, in which Creeks were forced to sign over land to the U.S. government.

Tensions between village independence and national control continued after the Red Stick War. Nowhere did this become more apparent than in the career of William McIntosh. In the 1810s and early 1820s, McIntosh (who, like McGillivray, had a Scottish father and an Indian mother) helped create a centralized police force called “Law Menders,” establish written laws, and form a National Council.

These reforms came back to haunt McIntosh when he signed the Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825. In 1821, in the First Treaty of Indian Springs, Georgia government officials bribed McIntosh into signing away pieces of Creek land in return for a 1,000-acre plantation along the Ocmulgee River, where McIntosh kept enslaved African Americans and built a hotel. In 1825, in the Second Treaty of Indian Springs, McIntosh, along with only six other Creek chiefs, signed away all Creek land east of the Chattahoochee River for $200,000, eliminating any Creek claim to land in Georgia. This treaty violated a law, which McIntosh had originally supported, against ceding land to the United States without the full assent of the Creek Nation.

By signing away all Creek lands in Georgia, McIntosh defied most of the reforms that he had encouraged. As a result, on April 30, 1825, the Law Menders, with the support of the National Council, set fire to his plantation, Acorn Bluff (or Lockchau Talofau in Creek) in Carroll County, and summarily executed him.