'Eyeball' planet spied by James Webb telescope might be habitable

Located 50 light-years from Earth, the beady-eyed exoplanet LHS 1140 b could be a perfect candidate for discovering liquid water outside the solar system, new research suggests.

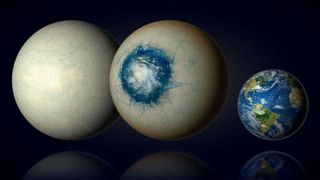

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found that a distant world discovered several years ago could be an "eyeball" planet with an iris-like ocean surrounded by a sea of solid ice — making it a candidate for a potentially habitable world.

The exoplanet, called LHS-1140b, was first discovered in 2017. Initially, it was thought to be a "mini-Neptune" swirling with a dense mixture of water, methane and ammonia. But the new findings, accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and available on the preprint server arXiv, suggest that the planet is icier and wetter than scientists thought. That means it could support life.

"Of all currently known temperate exoplanets, LHS-1140b could well be our best bet to one day indirectly confirm liquid water on the surface of an alien world beyond our Solar System," first author Charles Cadieux, an astrophysicist at the University of Montreal, said in a statement. "This would be a major milestone in the search for potentially habitable exoplanets."

Related: James Webb telescope spots wind blowing faster than a bullet on '2-faced planet' with eternal night

Located 50 light-years from Earth, LHS-1140b is roughly 1.73 times wider than our planet and 5.6 times its mass. It is tidally locked to its host star. This means it rotates at the same rate as it orbits its star, keeping its 2,500-mile (4,000 kilometers) melted eye fixed on the cosmic fire. Bound on a close orbit with its star, one year for the planet is just under 25 Earth days.

If LHS-1140b's star were a main sequence star like the sun, an orbit of this distance would boil its oceans and make it completely uninhabitable. But because it is a cooler red dwarf, this short distance places the planet right in the middle of the "Goldilocks zone" — the perfect distance from its star for liquid water to exist on the planet.

To study the exoplanet, the researchers used JWST's Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, which enables the telescope to assess the planet's contents as light from its star passes through the planet's hypothetical atmosphere to reach Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By looking at the wavelengths of light absorbed, the astronomers spotted signs of nitrogen, a key ingredient in Earth's atmosphere. Separate calculations also revealed that the planet isn't dense enough to be made of rock.

Taken together, these results seem to rule out a rocky or a mini-Neptune world in favor of one encased in an icy sea.

While most of the planet could be frozen solid, the researchers noted that the "iris" side could reach 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) on its surface — warm enough to create a habitable pool for marine life on the frozen world.

"Detecting an Earth-like atmosphere on a temperate planet is pushing Webb's capabilities to its limits — it's feasible; we just need lots of observing time," co-author René Doyon, a physicist at the University of Montreal, said in the statement. "The current hint of a nitrogen-rich atmosphere begs for confirmation with more data. We need at least one more year of observations to confirm that LHS 1140b has an atmosphere, and likely two or three more to detect carbon dioxide."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.