Fort Sumter: How Civil War Began With a Bloodless Battle

A mule was its only fatality, but the Battle of Fort Sumter nevertheless led to the United States' deadliest war, as historian Mark Jenkins recounts.

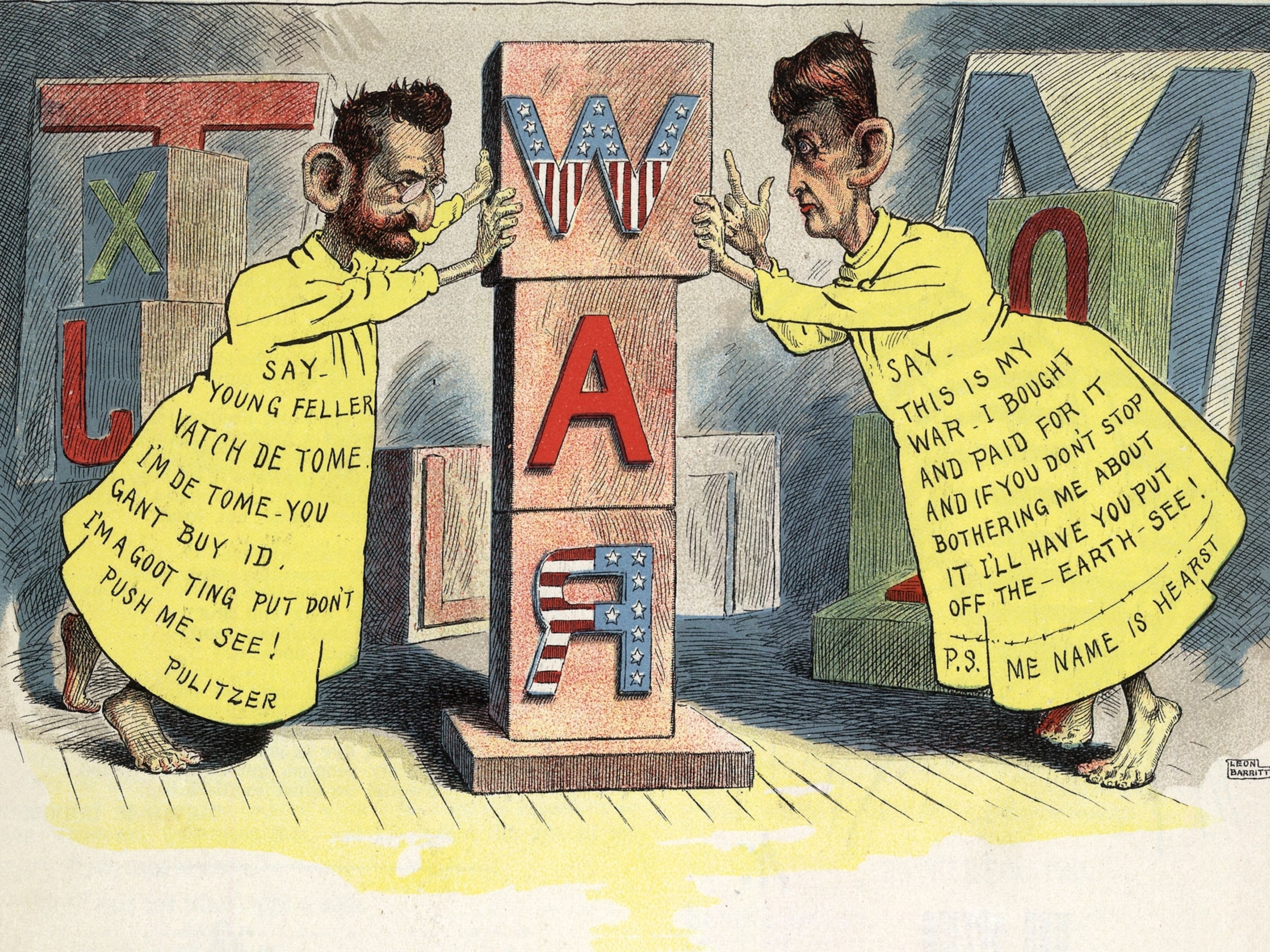

During the winter of 1860-61, the citizens of Charleston (map), South Carolina, were so sure that no war would follow their recent move to secede from the United States of America that the fiery editor of the Charleston Mercury supposedly vowed to eat the bodies of all who might be slain as a result.

Not to be outdone, former U.S. Senator James Chesnut, Jr., promised to drink any blood spilled. After all, "a lady's thimble," as a common saying had it, "will hold all the blood that will be shed."

Perhaps the most visible reminder to Charlestonians of the U.S. government's dominion over them was in their harbor, where atop the lonely bulk of Fort Sumter the Stars and Stripes still flew (pictures of Fort Sumter before and during the Civil War).

The November election of the notably antislavery Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States had so angered seven slave-owning states that they had chosen to secede and form their own union. Roughly five months later, on April 12, 1861, decades of high-flown oratory were reduced to a struggle for that pile of brick and mortar.

(See National Geographic Traveler magazine's top ten U.S. Civil War sites.)

Fort Sumter in First Line of Defense

Fort Sumter was only one in a series of imposing masonry fortresses, decades in the building, which studded the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts from Maine to Texas.

The nation's single biggest public expenditure and traditionally its first lines of defense, these symbols of sovereignty once carried an aura of impregnability—from without, if not from within.

During the four months leading up to Lincoln's Inauguration, the seceding states, one after another, seized federal forts, arsenals, and customs houses within their borders.

There was little to oppose the breakaway forces, a caretaker and a guard or two comprising many of the garrisons. Most of the 16,000 or so regular Army soldiers had been posted to the western frontier to protect settlers against the perceived threat from American Indians.

Civil War Inevitable?

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln was inaugurated, promising the seceding states that he would use force only "to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places" belonging to the federal government.

The stage was set for the inevitable showdown.

As of March, only four Southern forts were still under federal control. Two of them, Forts Taylor and Jefferson, were remote way stations in the Florida Keys. They would remain in government hands, useful as prisons and coaling stations throughout the four years of the coming Civil War.

The other two federal forts, however, became pawns in a game of war or peace.

The Civil War might as easily have erupted at Fort Pickens, outside Pensacola, Florida, as at Fort Sumter. Seen as easier to defend than smaller bastions nearby, both forts had been hastily garrisoned early in the secession crisis. (Read "Civil War Battlefields" in National Geographic magazine.)

Though the plight of both garrisons remained in the public eye, Fort Pickens stood to the outside of Pensacola Bay, while Fort Sumter was positioned in the middle of Charleston Harbor, surrounded by hostile batteries. Sumter, therefore, became a symbol of contested sovereignty.

Neither the new President nor the new Confederacy could afford to lose face by surrendering the Charleston fort. The only question was, who would shoot first?

In early January the South Carolinians had actually done so, turning away the Star of the West, a federal supply ship, with gunfire. But those were more or less warning shots that kicked up plumes of spray but caused no damage.

(See Civil War reenactment pictures.)

The Battle of Fort Sumter

As March turned to April, Lincoln, having dispatched another relief fleet to supply the beleaguered and increasingly hungry garrison, was willing to shoot his way through if need be.

Lincoln soon thought better of it, however, instead informing the rebellious Southerners that the fleet would carry only supplies into Sumter. The warships would remain outside the harbor.

Should the Confederates choose to fire on this "mission of humanity," as Lincoln called the supply run, they would then become the aggressor.

The Confederate government, knowing that its claims to sovereignty depended on no "foreign" power occupying any of its coastal forts, decided to act before the relief expedition arrived.

Confederate leaders, therefore, ordered Charleston's chief military officer, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, a flamboyant Louisiana Creole, to demand Fort Sumter's surrender. Should that be refused, he was to open fire on the stronghold.

James Chesnut, Jr., the former U.S. senator who'd pledged to drink the blood of casualties, was one of two emissaries who delivered the ultimatum to an ashen-faced Anderson at 3:25 a.m. on April 12, 1861—150 years ago today.

(Related: "Civil War at 150: Expect Subdued Salutes, Rising Voices.")

An hour later a signaling shot curved high in the sky and burst directly over the fort. A cacophonous barrage erupted, as 43 guns and mortars opened up on Sumter.

The pyrotechnic uproar had soon summoned all Charleston to the rooftops, where the citizens spent a sleepless night, watching the arcs of mortar shells. They spent the following day deafened by the din, peering through the smoke.

According to Union accounts, the noise was indescribable within the Fort Sumter's brick gun enclosures, but Anderson's men gamely returned fire, discharging about a thousand rounds as opposed to the almost four thousand shells that smashed into their walls or dropped into their courtyard.

Fires were devouring the barracks and edging dangerously close to the powder magazine by the time the white flag came fluttering up Sumter's flagstaff, some 34 hours after the bombardment had begun.

The opening gunfire of the Civil War—the first shots exchanged in anger between the United States and the Confederate States—then fell silent. (Interactive Map: Battlefields of the Civil War.)

As the smoke cleared the toll of battle was taken, and it amounted to one mule. Not a single person had been killed (though one man soon died in an accidental explosion). The South had indeed won the contest over that symbol of sovereignty without spilling enough blood to fill a thimble.

Or had it?

Fort Sumter Battle a "Bolt From the Sky"

By firing first, the Confederates had allowed Lincoln to claim the high ground. On April 15, some 75,000 Union loyalists volunteered to help "repossess the forts, places, and property which have been seized from the Union."

The Northern states fell in behind Lincoln, while Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee duly tumbled into the Confederacy.

But the Battle of Fort Sumter was a call to arms for both sides. The great convulsion had come at last, releasing stresses accumulated over generations of sectional strife.

"We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky," wrote the ex-slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and the "cry now is for war, vigorous war, war to the bitter end. ... "

Huge, flag-waving crowds gathered in cities and towns across the country, flushed with a kind of mass hysteria, a contagious abandon, an almost suicidal zeal. "It is a war of purification," claimed Virginia's Governor Henry Wise, "You want war, blood, fire, to purify you."

Hundreds of thousands of young militiamen, parading by torchlight to the dazzle of fireworks and the music of bands, soon marched into the crucible. Many of them would never return, for the war that was ignited that April night would eventually cost nearly 620,000 men their lives—2 percent of the United States' population at the time, and nearly as many as those killed in all the country's other wars combined.

The shooting was practically over by April 14, 1865, when—four years to the day after the Stars and Stripes had been lowered in defeat—the U.S. flag again rose over the rubble of Fort Sumter. But one more bullet found its victim that night. While watching a play in Washington, D.C.'s Ford's Theater, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

The dislocations of the Civil War "wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character," as writers Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner put it in 1873, "that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three generations."

Nearly five generations have now passed since the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, and still their reverberations are being felt.

Mark Collins Jenkins, a historian formerly with the National Geographic Society, is co-author of the new book The Civil War: A Visual History.

MORE FORT SUMTER AND CIVIL WAR COVERAGE

- Full Coverage: Civil War Sesquicentennial

- Pictures: Fort Sumter—Defiance and Destruction (1862-1865)

- U.S. Civil War Prison Camps Claimed Thousands

- Civil War Wreck Rises Again: Restoring the Monitor

- Hunley Findings Put Faces on Civil War Submarine

- Gettysburg: From Battlefield to Civil War Shrine

- Civil War Sub May Have Been Downed by Unsealed Hatch

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How Moo Deng the pygmy hippo is different from common hipposHow Moo Deng the pygmy hippo is different from common hippos

- Wombats have buns of steel—and they poop in cubes. Here's why.Wombats have buns of steel—and they poop in cubes. Here's why.

- Why manatees often lurk close to Florida's power plantsWhy manatees often lurk close to Florida's power plants

- This Ecuadorian frog was lost for 100 years—until nowThis Ecuadorian frog was lost for 100 years—until now

Environment

- This little bird tells the story of the East Coast’s disappearing marshesThis little bird tells the story of the East Coast’s disappearing marshes

- ‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained

History & Culture

- The 5 scariest mythological witches from around the worldThe 5 scariest mythological witches from around the world

- Meet Emiliano Zapata: hero and martyr of the Mexican RevolutionMeet Emiliano Zapata: hero and martyr of the Mexican Revolution

- Everything you need to know about Hispanic Heritage MonthEverything you need to know about Hispanic Heritage Month

- Your favorite foods have surprising global originsYour favorite foods have surprising global origins

- How did ancient Egyptian obelisks end up all over the world?How did ancient Egyptian obelisks end up all over the world?

Science

- Why this type of carb is so good for your gut healthWhy this type of carb is so good for your gut health

- Is America’s legal alcohol limit for driving too high?Is America’s legal alcohol limit for driving too high?

- This Ecuadorian frog was lost for 100 years—until nowThis Ecuadorian frog was lost for 100 years—until now

Travel

- This British seaside resort is famous for fossil-huntingThis British seaside resort is famous for fossil-hunting

- The 10 best hotels in Spain for every kind of traveler

- Travel

- Destination Guide

The 10 best hotels in Spain for every kind of traveler - 10 ways to see a different side of Spain

- Travel

- Destination Guide

10 ways to see a different side of Spain