Why this once isolated tribe took up cell phones and social media

Indigenous peoples in the Amazon are using modern technology to defend their land—and their way of life. “We want the world to see us so they can help us.”

The Javari River splits Brazil and Peru as it flows deep into the Amazon forest. The only signs of human life along the waterway are the occasional boat or dock on the Peruvian side. On the Brazilian bank, government signs warn that this is Javari Valley Indigenous land, a reserve that’s home to the highest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples in the world. Outsiders are forbidden to enter, but the lure of abundant minerals, timber, and wildlife is impossible for many to resist.

Some 6,000 people are known to live in the reserve, an area of nearly pristine forest roughly the size of Portugal. But that number accounts only for members of seven tribes who have established contact with the outside world. I’ve come to see how these people, who live on an embattled frontier, are faring as illegal logging, fishing, and mining chip away at their ancestral home.

The village of São Luís sits about 200 miles up the Javari River from the town of Atalaia do Norte. It’s home to 200 or so Kanamari people, who have granted me and a film crew permission to visit. For eight days we live in their tidy settlement of wooden stilt houses, rising when Chief Mauro Kanamari (the Kanamari take the tribe’s name as their last name) blows a horn. We accompany the women as they harvest manioc, or cassava, and the men as they hunt and fish.

What we witness, again and again, are people who, worried about violent incursions into their forest, are increasingly finding new ways to defend their land and their way of life.

“There used to be only a few illegal invaders, fishermen, and loggers who took wood from our territory,” Chief Mauro tells us. “Now they are more with every day.”

For the Kanamari, the forest is their parent who supplies everything. Logging and other natural resource extraction threaten their parent’s health and their own livelihood. But it’s dangerous to oppose such activities. In 2022 Brazilian Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips were brutally murdered on another river in the region, allegedly by order of the head of a criminal fishing network. “I’ve personally received many threats,” says Chief Mauro.

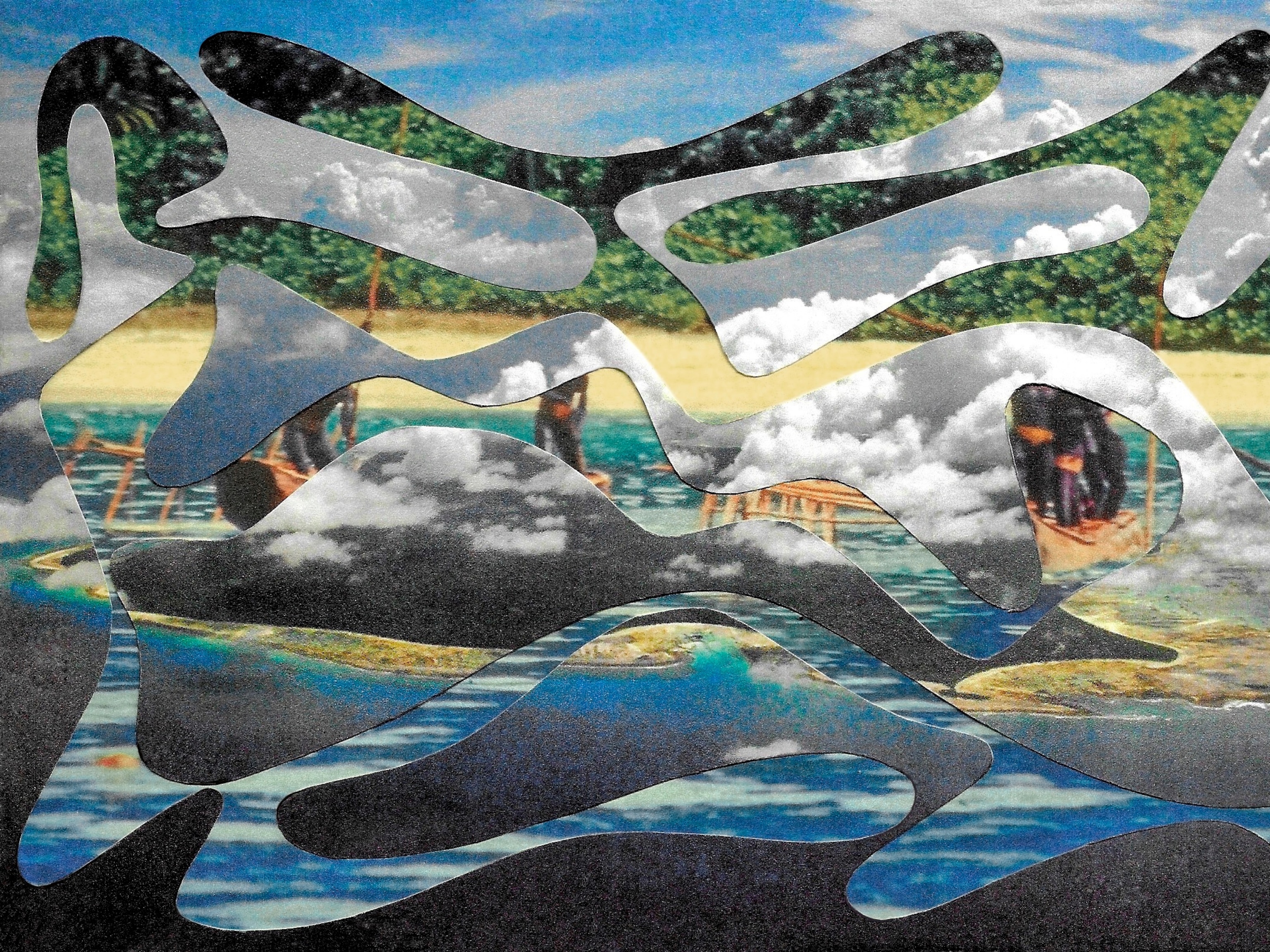

Still, the Kanamari refuse to allow these encroachments to go unchallenged. They’ve joined forces with FUNAI, Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency, and UNIVAJA, a union of the Indigenous groups in the Javari Valley, to organize vigilance patrols and push back against the outlaw loggers. FUNAI supplies radios and fuel for a motorized boat, but the Kanamari’s weapons—bows and arrows and small-caliber guns—are no match for those of the intruders. By necessity, their philosophy is to be nonconfrontational but to report what they find.

“We used to confiscate this wood, but now, since they’re coming in greater numbers, we’ve become afraid,” says Chief Mauro. “When you go to the city, then you’re marked for assassination.”

João Kanamari, Chief Mauro’s 20-year-old nephew, documents the patrols on his cell phone and shares the information on social media. In his late teens he was sent to Atalaia do Norte to learn Portuguese and serve as an interlocutor between his people and the rest of the world.

“We want the world to see us so they can help us,” João says. “We are out here on these dangerous waters patrolling our territory, not just for us but also for you. The Amazon is our government, our father, and our mother. We can’t survive without her, and, from what we all now understand, neither can you.”

This story appears in the January 2024 issue of National Geographic magazine.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Leopards are facing growing challenges. Can they endure?Leopards are facing growing challenges. Can they endure?

- 3 myths about bald eagles you might have thought were true3 myths about bald eagles you might have thought were true

- These ants perform life-saving amputations on each otherThese ants perform life-saving amputations on each other

- What Inughuit hunters can teach us about the narwhalWhat Inughuit hunters can teach us about the narwhal

- Meet the ‘giant’ river crabs that live beneath Rome’s ancient ruinsMeet the ‘giant’ river crabs that live beneath Rome’s ancient ruins

- This gorilla is 50 years old and still nursing orphans. Why?This gorilla is 50 years old and still nursing orphans. Why?

Environment

- What causes a rip current—and how can you spot one?What causes a rip current—and how can you spot one?

- The race to create climate-resilient coral—before it's too lateThe race to create climate-resilient coral—before it's too late

- Deb Haaland: Keeping tribal voices front and centerDeb Haaland: Keeping tribal voices front and center

- Aboriginal women are reclaiming traditions of fireAboriginal women are reclaiming traditions of fire

History & Culture

- Meet the ancient goddess of the Seine River: SequanaMeet the ancient goddess of the Seine River: Sequana

- Inside the wild (and painful) world of ancient Roman groomingInside the wild (and painful) world of ancient Roman grooming

- How 'Reservation Dogs' sparked a Native film boom in TulsaHow 'Reservation Dogs' sparked a Native film boom in Tulsa

Science

- Leopards are facing growing challenges. Can they endure?Leopards are facing growing challenges. Can they endure?

- What does rose water do? Here's a look at the scienceWhat does rose water do? Here's a look at the science

Travel

- The unlikely birthplace of Californian punk still rocksThe unlikely birthplace of Californian punk still rocks

- 5 lessons Benjamin Franklin taught me about traveling well5 lessons Benjamin Franklin taught me about traveling well

- B Corps can help us travel more responsibly—but what are they?B Corps can help us travel more responsibly—but what are they?