Livingstone and the Lion at the David Livinsgtone Centre in Blantyre |

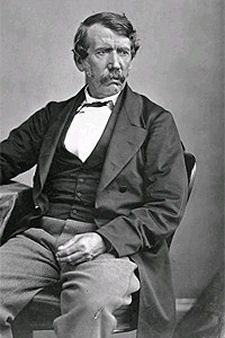

David Livingstone lived from 19 March 1813 to 1 May 1873. From a childhood of poverty he became one of the most famous of the European missionaries and explorers who opened up the interior of Africa during the mid 1800s. Such was his celebrity in his own day that when he died, his body was returned for burial in Westminster Abbey.

David Livingstone was born in Blantyre, at the time a mill village on the banks of the River Clyde some eight miles south-east of Glasgow. His mother and father were among the 2000 people employed in the Blantyre Cotton Mills and the family, including David's four brothers and sisters, lived in a single room in a tenement they shared with 23 other families in what was known as Shuttle Row. This now forms part of the David Livingstone Centre, a museum commemorating Livingstone's life and work in his native Blantyre.

At the age of 10, David Livingstone started work in the mill, working 14 hours each day for six day a week. Despite this he was able to educate himself, reading classics and exploring the surrounding countryside in his scarce spare time. He went on to study Medicine, Theology and Greek at the University of Glasgow. He then went to work in London, joining the London Missionary Society and being ordained as a Minister in 1840.

By 1841 Livingstone was working in Bechuanaland (now Botswana), and in his early years his focus was very much on his missionary work. In 1844 he was in the village of Mabotsa, in present day South Africa, when lions attacked and killed a woman from the village. Livingston shot one of the lions, which then attacked him, badly injuring his left arm before it dropped dead.

In 1845 David married Mary Moffat, daughter of the missionary Robert Moffat. The couple settled as guests of Chief Sechele and the Bachwain tribe, and it was from about the same time that David started to make trips into Africa's unknown interior. During this period Livingstone also established his lifelong opposition of the slave trade in East Africa, seeking to counter it with the development of other forms of trade and the introduction of Christianity. In 1853 he pioneered a route across southern Africa and in 1854 was the first European to see the Mosi-oa-Tunya waterfall, which he renamed Victoria Falls after his monarch, Queen Victoria.

Livingstone came back to Britain a hero, and wrote his best selling account of his travels: Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (1857). In 1858 he returned to Africa as head of the Zambezi Expedition, a British government-funded project to examine the natural resources of south-eastern Africa. Leadership was not Livingstone's greatest strength, and the expedition did not really live up to its potential or provide much return for the investment of its backers. Still worse, Mary Livingstone, accompanying the expedition, died on 29 April 1863 of dysentery. The expedition was recalled to Britain in 1864, accompanied by widespread press accounts of its failure.

In March 1866, David Livingstone went to Africa once again, this time to Zanzibar (now part of Tanzania), where he set out to seek the source of the Nile. His expedition ended up heading further south than intended, and some of his followers deserted him. Their reports that he had been killed led to headlines around the world. Meantime, Livingstone had discovered Lakes Mweru and Bangweulu, before arriving at Lake Tanganyika in February 1869. By now he was ill, but he pressed on, arriving at Nyangwe on the Lualaba River, a tributary of the Congo, in March 1871. No European had been so far west into central Africa's interior before.

Now very ill, Livingstone returned to Lake Tanganyika in October 1871. Here he had his famous "Dr Livingstone I presume?" meeting with Henry Stanley, a New York Herald reporter searching for Livingstone. Medicine carried by Stanley eased Livingstone's health problems, and when Stanley departed in March 1872, Livingstone declined to accompany him, determined to continue his search for the source of the River Nile. Livingstone died of malaria and dysentery on 1 May 1873, still without having found it. His body was carried overland to the coast for 1000 miles by members of his party, then returned to Britain for burial in Westminster Abbey.