Larry Charles is the Emmy-winning Seinfeld writer responsible for many of the comedy’s grimly hilarious story lines, and the two lost episodes of the series so controversial that they never aired. After directing Seinfeld’s co-creator Larry David on over a dozen episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm, the bearded, Brooklyn-born comic writer executive produced Entourage and linked up with Sacha Baron Cohen for a series of big-screen mockumentary projects including Borat, Bruno, and The Dictator. (His comedic appeal is so wide-ranging that both Bob Dylan and Kanye West reached out to him when they had ideas for comedy projects.)

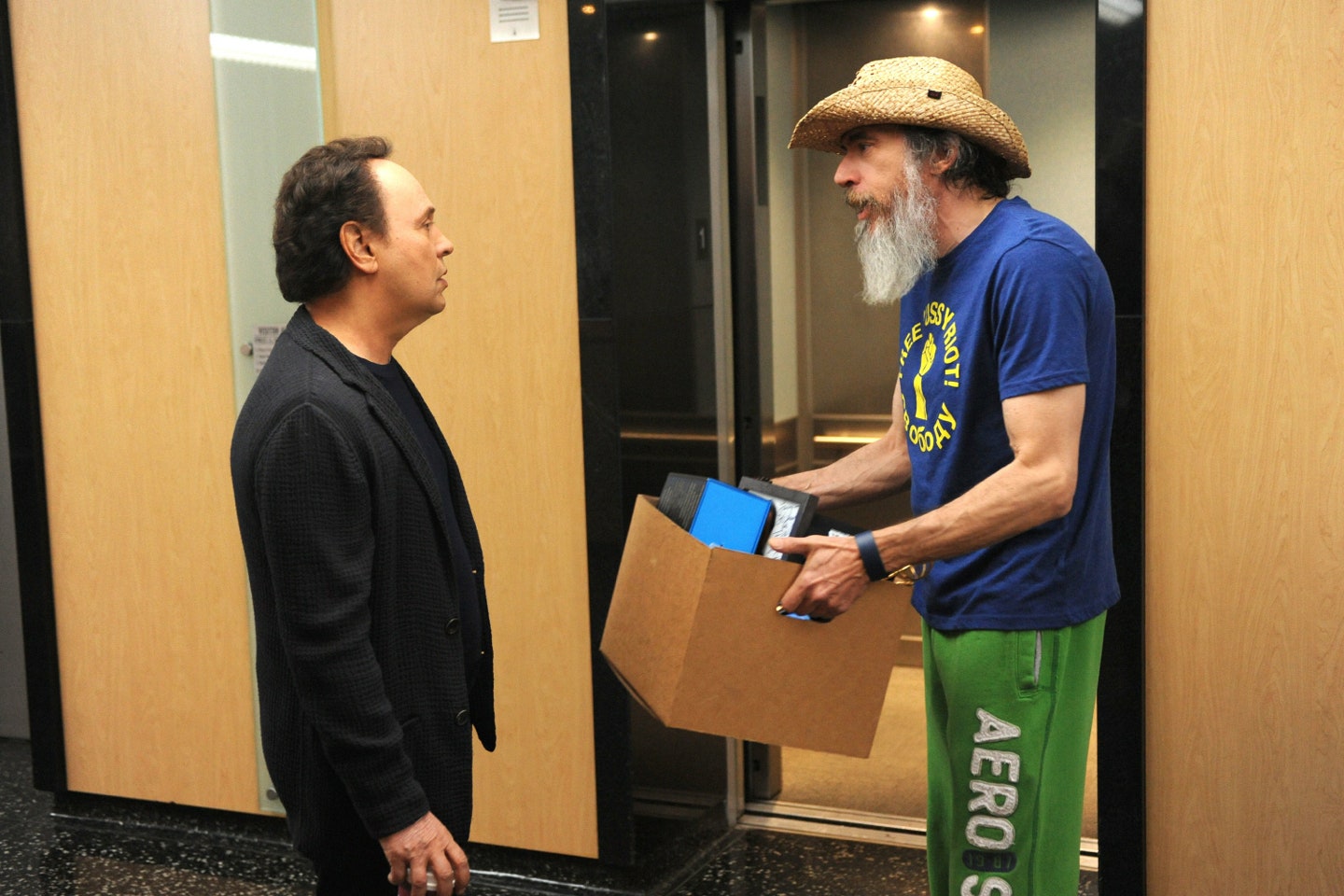

This Thursday, Charles returns to television with The Comedians, an FX series starring Billy Crystal and Josh Gad as heightened versions of themselves who co-star on a fictional comedy show. Based on a Swedish series, The Comedians has tones of Curb Your Enthusiasm and Seinfeld, with characters fumbling funnily through questionable social situations that, in this case, often arise from their generation gap. In anticipation of the show’s premiere, Charles phoned us from Morocco to chat about why it was funny to pair Billy Crystal with a bong, why those controversial Seinfeld episodes didn’t work, and what he is hoping for the Osama bin Laden satire he is making with Nicolas Cage.

VF Hollywood: If nothing else, thank you for giving us a visual of Billy Crystal wandering around a grocery store high in The Comedians after smoking weed.

Larry Charles: [Laughs] I’m such a fan of Billy’s and I tried to imagine, at this point in his career, what I might enjoy seeing him do. And deconstruct his persona a little bit. And he was very courageous about it and brave about it and went for it. . . . In the grocery store, we just sort of played. I remember getting there in the morning with Billy and literally walking down the aisles and going, “This’ll be funny. That’ll be funny.”

There are four creators listed on the credits. How did that work out exactly?

It was based on the Swedish series and the Swedish series was very dark. It was about an older comedian and a younger comedian—the two guys play themselves. So we had the premise of the show already, which is a gigantic leap. And then it was about Billy and taking advantage of who Billy is and deconstructing that persona. I think Billy has reached the point of his career where he is looking for challenges. He is not just going to rehash the same things he’s done. He can afford to take that risk even though he doesn’t need to take the risk.

And then it was just about finding someone to counterpoint him. I knew Josh because we had been working on this other project—I had directed him on New Girl and we are working on this [Sam] Kinison movie together, and I discovered him to be this incredibly great improviser and incredibly supportive.

How far do you and Billy go back?

I was a writer on [the 80s ABC sketch-comedy show] Fridays. That was my first TV job when I was 22 years old. My first staff job. Larry David was on that show and he became my mentor, really, from that show. And we had guest stars on that show at the time. And Billy was doing Soap and he was one of the guest stars. So I met him and got to know him a little bit back then. So we have kind of known each other informally for about 35 years.

How does your comedy partnership with him differ from the partnerships you’ve had with Larry David and Sasha Baron Cohen?

I’ve been very lucky to sort of collaborate with truly comical geniuses. Billy has so many arrows in his quiver. He can sing. He can do impressions. He can be dramatic. He can be emotional. Besides obviously being funny with the script and off the cuff, he has a lot of weapons at his disposal. Sasha and Larry both do their things. But Billy’s thing is very eclectic. He has a very broad range. If you watch him on the Academy Awards or in one of his movies, you see that he can move through a lot of different levels with great ease. And no matter how dark it gets, he has an ability to somehow keep it light, which is a quality that I think all great comedians have. That makes it very palatable to the audience. So you can take the audience down these darker paths because they trust him the way they trust Jerry Seinfeld, who is also willing to go down very dark paths, but just inherently kept it light. That combination is kind of an innate thing. You either have it or you don’t, and Billy has that.

Do you feel that Curb Your Enthusiasm has inspired a new genre of television—I feel like there are more and more shows featuring well-known people playing fictional versions of themselves.

I would like to think that. I hope it has and I am proud to be part of that. I also think that there are a number of other sources as well that we’re drawing on. Louie was a massive influence on the show as well. Before we were even writing the first episode, we would watch Louie and just come in and go, “Wow, did you see that episode?” He went from hilarious comedy to very dark places. He allowed the story to have a kind of stream of consciousness flow to it and I really, really admired that. That’s something I aspired to . . . to break down the traditional stories and deconstruct them and see what’s underneath the narrative a little bit and discover on the way. And Louie, I think, was kind of a natural child of Curb and Seinfeld and takes it one step further.

Speaking of comedy that goes to very dark places, you are somewhat famously responsible for the two controversial episodes of Seinfeld that did not air—one of which had to do with George making the observation that he had never seen a black person order a salad . . .

I did write an episode about George making an offhand comment about never seeing a black person eating a salad that comes back and explodes in his face. That’s true, yes. The network wasn’t comfortable with that, and I think you’re probably also going to bring up the gun episode, which even had gone a little bit further. We had cast that episode, built the sets, began to rehearse it, and there was just a lot of discomfort. Both those episodes wound up not getting produced.

How do you feel about the episodes now that 25 years or so have gone by?

In retrospect, when I think back on it, it was early in the run of the show and I was still figuring out how to do this . . . and I think Larry and Jerry were very supportive, but I wish that I had figured out a way—because this is what Larry David is so brilliant at, both in Seinfeld and in Curb. . . he can take a premise that would basically not be a comedy or a comedic premise, and he finds a way to do that. I was very influenced by Larry and most of my Seinfeld episodes, I was able to figure that formula, crack that code so to speak. But in those two episodes, I knew there was something funny in them, and dark at the same time, but I could never crack the code of those episodes and thus they were not quite ready to be produced. Even though I appreciate the fact that they almost were. I kind of understand why those didn’t work out.

There is a very funny episode of The Comedians that deals with race in a clever way. Do you think you are able to joke about that because it is several decades later, because this show is on a cable channel versus a network, or just because you had a better story idea?

I think it’s kind of a paradox ironically. I think in some ways, because of cable, because of language loosening up, and cable shows like Louie and Curb coming along, there is a lot of subject matter that you can deal with that you couldn’t in the 90s. At the same time, there is even more political correctness in certain subjects, which makes it even more sensitive. And race is a certain subject that is always a sensitive subject. I think with that episode, we kind of just nailed that tone. You can relate to Billy and Josh wanting to diversify their workplace. You can relate to Billy and Josh sort of being stuck in their old ways. You can relate to all of their discomfort and awkwardness in it. And that’s why that episode really, really worked. And maybe that’s why the Seinfeld episode . . . I wasn’t able to do something that sophisticated at that time.

You mentioned that you want to explore some dark subjects in comedy that might make people uncomfortable. What do you think it is about your background that makes you willing to go to those places.

I’m from the part of Brooklyn that is the breeding ground for great comedy. I am very lucky that I just happened to be born there and grew up there. So you have Larry David. He is about 10 years older than me. He grew up like 10 blocks from me. Mel Brooks is from that neighborhood. Woody Allen is from that neighborhood. [Catch-22 author] Joseph Heller is from that neighborhood. It goes on and on. Great comic minds.

There is a lot of hardship, a lot of darkness, a lot of anger, a lot of fear, a lot of the things that people are not proud to feel. But in order to survive it and transcend it and embrace it, humor becomes a tool to sort of protect yourself from it. It becomes your armor. You develop a verbal armor to deal with it. All of those guys kind of come from the same background. The subway was running. The elevated line ran above Brighton Beach Avenue. It was just hard to be heard. There was kind of a hierarchy of people preying on each other constantly. There were gangs. There was violence. It was very much like Lord of the Flies to some degree. I think that is where this paradox of this darkness and this very serious view of the world that I think I share with Mel and Larry and Joseph Heller and people like that as well as the comic voice that it sort of filters through.

I feel like you’ve worked with people who are kind of geniuses in their chosen profession but have a reputation for being difficult—like Larry, Bob Dylan, Kanye West. . . What is it about you that makes a good collaborator with these types of personalities?

Not to keep drawing on Brooklyn but in order to survive in Brooklyn, you have to deal with a lot of difficult people. People who are not being straight with you. People who lie to you or try to take advantage of you or bully you or do all kinds of things that are not nice and so you need to learn with how to deal with it or else you succumb to it. Me, I kind of learned how to deal with tough personalities and kind of enjoyed the complexity of these difficult personalities. And I think the lessons that I learned in Brooklyn, I was able to luckily apply to my work.

Are you still in touch with Kanye?

I am in touch with him occasionally. He is so busy now. I still can’t believe to this day that HBO turned down the show. It was super-funny. It had a great cast—J.B. Smoove was one of the regulars. I don’t know that he would ever want to revert back to that now. He is someone who keeps moving forward and continues to explode in all media. I doubt I would be able to tie him down again to do a show like that, unfortunately. Although I loved working with him. The very first thing he ever said to me was, “I'm the black Larry David.” He's very self-aware. Very bright. Very funny.

Has your sense of humor changed since Seinfeld?

I think it’s evolved. I remember in the first season I was working there, I would often sit with Larry and I would go, “You know, I really don’t see myself as a comedy writer.” And he would say, “I wish you had told me that before.” I think I see things from a slightly broader perspective than I used to. I’m not as desperate to succeed and ambitious as I was then, so I am more interested in getting deeper and getting inside of things more.

You are in Morocco about to film Army of One with Nicolas Cage, who seems to be another one of these brilliant-but-mad creative types. And there are so many shades of Nicolas Cage performances . . . what should we expect from him in this project?

Nicolas Cage is one of our great treasures in American acting. He is an iconic person and he is somebody who completely immerses himself, almost in kind of a parallel way to Sasha. He just immerses himself in a character. And I think, once again, people will be blown away. Their eyes will be opened. It will be a revelatory performance. I think it will also be supremely compelling and entertaining.

Army of One is based on a GQ article about a construction worker who goes out on his own to track down Osama bin Laden. What kind of tone will the movie have?

I think it’s definitely a comedy. It’s definitely satire. It’s got a lot of emotion. It’s got a lot of suspense. It’s got a lot of hilarity. And it’s kind of absurd on a certain level. What I try to do with these movies, and even with Seinfeld or Curb, I try to make them as dense as possible with ideas, notions, and concepts that you can revisit upon revisiting it. Like a great record. When you listen to a great record, you want to go back and listen to it again and again and again, and over the years, you have a different relationship to it, like a great Bob Dylan song. And that’s how I am taking this.