In any beloved TV series, you can look back on a few scenes that’ll tell you exactly what the show is going to become. In the case of Bridgerton, one need not look very far.

The pre-credits “presentation sequence,” as writer-creator Chris Van Dusen calls it, of the series’ pilot episode immaculately establishes the tone, heart, and conflict of the luscious eight or so hours that follow. “Today is a most important day, and for some a terrifying one,” Julie Andrews’s Lady Whistledown narrates about the scene. “For today is the day London’s marriage-minded misses are presented to Her Majesty, the queen. May God have mercy on their souls.”

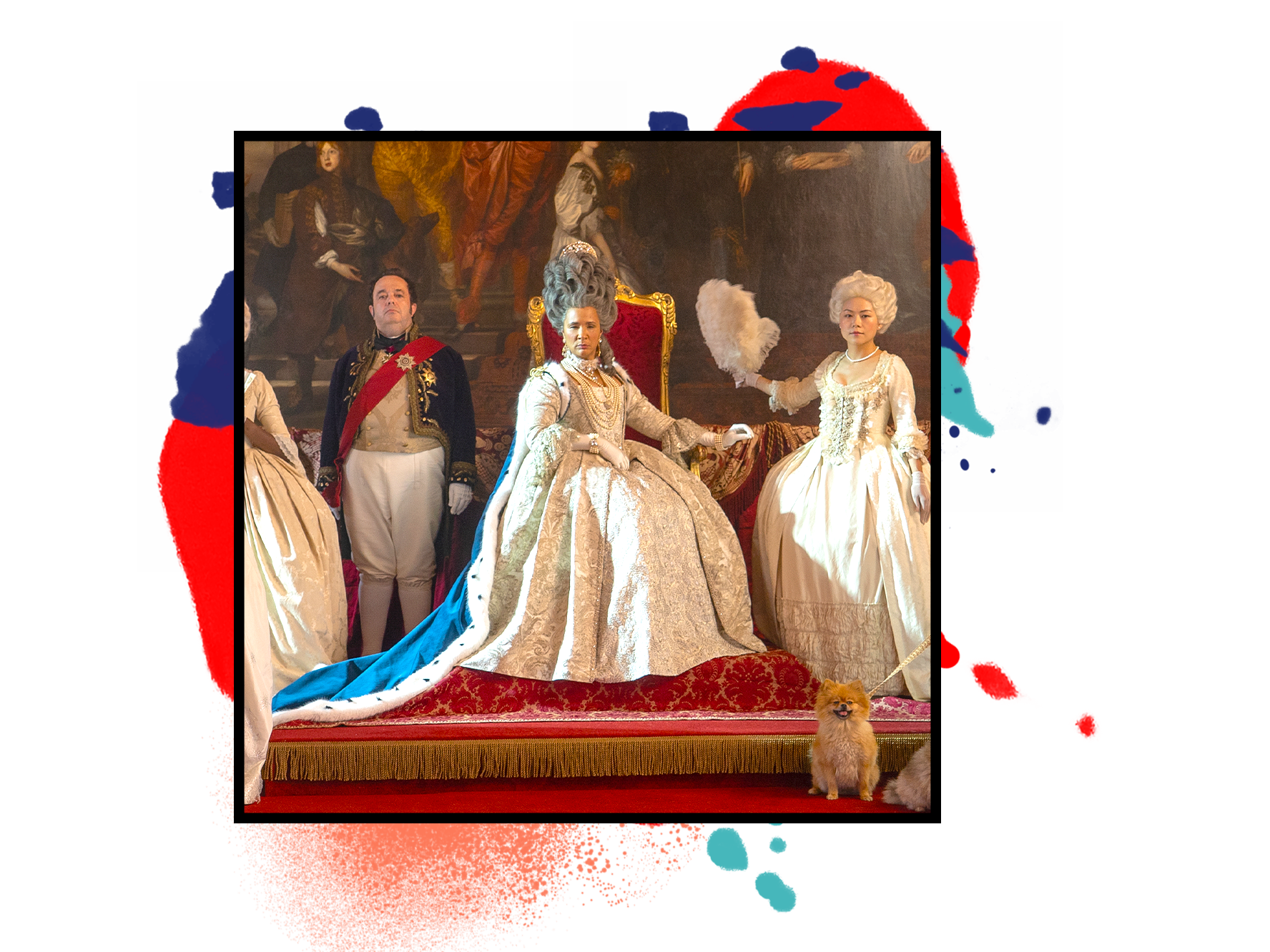

Vanity Fair gathered Van Dusen, director Julie Anne Robinson, star Phoebe Dynevor (who plays protagonist Daphne Bridgerton, also introduced here), and Queen Charlotte herself, Golda Rosheuvel, to discuss the making of this most important, terrifying moment.

Van Dusen had been working on the Shonda Rhimes-produced Bridgerton for several years before it premiered on Netflix last Christmas, which meant plenty of rewrites and reimaginings of his take on Julia Quinn’s Regency novels. This scene, however, remained mostly intact. “It was actually one of the very first set of scenes that I remember writing for the show,” Van Dusen says—despite the fact that it doesn’t appear in the original books at all.

Logistically, much gets accomplished here. It’s an overarching preview of the Bridgerton world, with Queen Charlotte inviting “all of the young ladies of marriageable age to the palace, so that their [mothers] can present their daughters and all of their beautiful finery to the queen, and thereby mark their official coming-out,” Van Dusen explains. Pulling this off required a certain level of scale in the scene’s look. “The biggest challenge was to make this event feel extremely opulent, extremely full,” says Robinson. “The richest 500 people in society [were] in this room. We had a lot of lovely costumes, but we didn’t have enough. So we had to, through camera trickery, create a sense of richness and opulence that may or may not have actually existed in the room.”

While there’s a solid amount of character work to be done, with first looks at both the queen and Daphne on the docket, we’re initially greeted by the bumbling Featherington sisters. They get the first presentation, ahead of Daphne, and Robinson revels in their clumsiness, holding the camera on them squishing through the door before ending their segment on a hilariously humiliating collapse (more on that later). “We’re establishing a slightly comedic tone with the Featheringtons,” Robinson says. “We found a lot of that in rehearsals.”

Everyone’s attention, both in the scene and at home, then turns to Daphne, the camera close on her wide eyes as she nervously enters. “It’s the beginning of her journey—and it’s also the end of her dreaming about this moment her whole life,” Dynevor says of her approach to playing the scene. “Suddenly, it’s happening.”

Whenever the presentation sequence hinges on Rosheuvel’s Queen Charlotte, you dread the moment when the camera cuts away. This goes from the first delicious image of her, slouching on her throne in disdain—“and bored, as well,” Rosheuvel is sure to note with a laugh. Robinson crafts the opening as a long tracking shot with the Featheringtons slowly approaching. Such careful, impactful filmmaking was essential to Van Dusen’s vision here. “You immediately see that the most powerful person in this world is a woman of color,” the creator says. “That tells you something absolutely integral about the show—this is a world where the color of your skin doesn’t determine whether you’re high born or low born…. It tells you that Bridgerton isn’t going to be your typical period piece.”

Rosheuvel remembers first walking onto the Wilton House set—where the royal palace sections were filmed—and despite the archness of the character, feeling a real grounding in the moment. “Knowing that this happened, this was a true, real thing happening back in the 18th century…gives it a sense of history,” she says. “To sit there on the throne and survey the room—there’s a lot of power, a lot of ownership, that you can take just by doing that.” The character’s nasty streak—first apparent when she dismisses the Featherington sisters upon their entrance with a gesture and without a word—was easy to embody. “I have a little bit of a wicked streak in me anyway,” Rosheuvel cracks. “To bring that layer of wickedness to the queen—it just comes naturally, darling.”

The whole affair, combining the queen’s contempt with the Featheringtons’ buffoonery, borders on silly—the score is jubilant and upbeat, the blocking edges toward slapstick. “You want to absolutely imbue the scene with all of the stakes that we’ve spoken about, but still let the audience in a little bit on the tone that’s going to be slightly irreverent in places—that it’s going to be fun,” Robinson says. This culminates in one young Featherington fainting to the floor after facing the queen’s rejection, with the crowd gasping. This isn’t just for laughs, though, as it also sets up a central contrast in the series. “Something Julie and I spoke a lot about [was] the Bridgertons being the harmony to the discord of the Featheringtons—they’re total opposites,” Van Dusen says. “The Bridgertons, they can do no wrong, they’re absolutely perfect, but the same can’t be said for the Featheringtons…. It was crucial to really establish those kinds of distinctions from the beginning.”

From the second the Featheringtons exit, the scene takes a dramatic turn. The music and camerawork do some of the work to indicate as much, but Dynevor must ultimately sell the big shift. Robinson often tells the story of how she wondered whether the actress could pull it off, watching her “stomping in” on the first day of rehearsal (“with my Birkenstocks or whatever I was wearing,” Dynevor adds, smiling). But Dynevor rose to the occasion, first passing etiquette training with flying colors. “The curtsy that Phoebe had to learn—it isn’t easy to curtsy that deeply, repeatedly, take after take,” Robinson says. “Then there’s the posture which she had to work on, with the choreographer, and just moving through the space. All of that was completely new and something that [she was] able to inhabit completely.”

Dyenvor took it beat by beat, finding guidance in the scene’s structure. “Daphne is the one that’s really in the moment; this is do or die for her, which is ridiculous, but in its own way,” she says. “Having that space to rehearse and knowing, ‘Okay, that’s how the Featheringtons come down, they have their fall, and then [there’s] the contrast of that with Daphne—that was very helpful in informing how it was going to all play out.” Adds Van Dusen of orchestrating the flow, from the Featheringtons to Daphne: “We looked at this as one big dance. The camera was moving.”

The music subtly builds tension as the queen regards Daphne; then, it’s as if she experiences a jolt before slowly, quietly rising. “We had to choreograph me getting up off that chair because the weight of the costume and the wig and the big royal train in the back had to be managed and maneuvered,” Rosheuvel says. “It had to be all timed to perfection so that I didn’t fall on my ass. That could have happened quite easily.” The serious mood feels stark as the queen walks toward her, but there’s surprising tenderness as she tilts Daphne’s head up with her hand, flashing a rare smile.

“I imagined it [would] be a little more stern, like, ‘You’re fine, you’re great,’ but there was such a vulnerability. It made me loosen up,” Dynevor recalls. “It’s a really personal moment, which is such a huge deal because it’s the Queen of England, and she’s taking Daphne into her arms and saying, ‘I accept you.’” Rosheuvel adds that this was a deliberate, careful choice on her part: “The connection between Daphne and the queen had to be human…. These characters have to be relatable too, for people to get into the screen and come on this journey with them. Getting up and walking down, greeting this beautiful woman—it had to be human.”

Once the queen describes Daphne as “flawless,” the score soars in triumph—setting the stage for our heroine’s season-long romantic odyssey. “This is what she’s been trained and raised for. It meant everything,” Van Dusen says. “It was a big moment in any young lady’s life.” This makes for a vital introduction to Daphne, even though Dynevor says that Phoebe was originally supposed to feature in a relatively standard first appearance. “That scene was cut, before, where you actually meet her and she speaks, and instead this becomes the first scene,” Dynevor reveals. “It’s such an interesting choice, but I think ultimately it was the best choice.”

Why? “This is the moment, as Daphne later says, her entire life has been reduced to,” Van Dusen says. “I always thought of this as her Super Bowl.”

— The Making of Mare of Easttown’s Flirtatious, Sad Bar Scene

— Elizabeth Olsen on Reclaiming Her Power in WandaVision

— How William Jackson Harper Brought Hope to The Underground Railroad

— A Golden Globe Voter Speaks Out About Her HFPA Resignation

— Why Is Gina Carano on the Emmy Ballot for The Mandalorian?

— Sign up for the “HWD Daily” newsletter for must-read industry and awards coverage—plus a special weekly edition of “Awards Insider.”