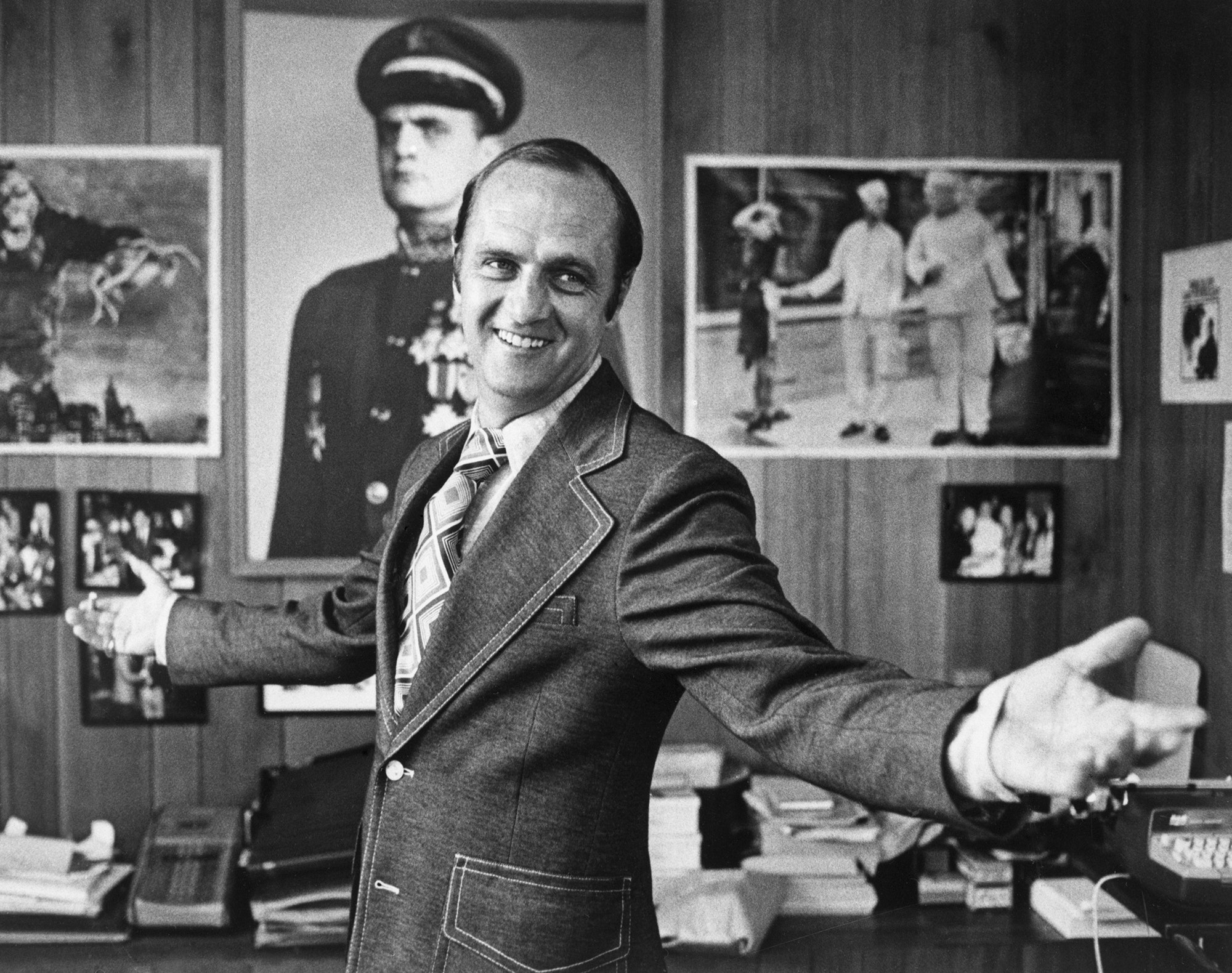

Bob Newhart, everyman comedian and star of two beloved sitcoms that bore his name, died Thursday at the age of 94. The news was announced by Jerry Digney, Newhart’s longtime publicist.

Beneath his mild-mannered appearance and stylized stammering delivery beat the heart of one of stand-up comedy’s most unexpected and subversive voices. “Being a comedian means you are anti-authority . . . at heart,” he wrote in his 2006 memoir, I Shouldn’t Even be Doing This. “You are looking to expose the loopholes in the system.”

He did not look the part. Perhaps the defining stand-up comedian of the Mad Men era, Newhart’s clean cut, “buttoned-down” façade belied a sharp satiric mind that questioned nine-to-five bureaucracy and corporate institutions. As Gerald Nachman observed in his book Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s, “He wasn’t a fast-talking radical like Mort Sahl, a ball of nerves like Shelley Berman, a neurotic dweeb like Woody Allen, a frenzied profane hipster like Lenny Bruce, a sophisticated observer of social manners like [Mike] Nichols and [Elaine] May, a zany like Jonathan Winters and Phyllis Diller. He was . . . the classic little man caught in the system.” Or, as Newhart himself once described his persona, “the only sane person in a world gone completely mad.”

Much like Berman, Newhart’s signature was monologues that depicted one half of a conversation; a driving instructor guiding his pupil, a game manufacturer dismissing Abner Doubleday’s idea for baseball, a press agent coaching Abraham Lincoln on his Gettysburg Address (“You changed four-score and seven to eighty-seven? Abe, that’s meant to be a grabber”).

In essence, Newhart was his own straight man, equal parts actor and reactor, with the audience filling in the unheard dialogue. “What I’m saying is not necessarily funny,” he explained in a 2014 NPR interview. “It’s what you don’t hear that’s funny, and the audience supplies that. It presumes a certain intelligence on the part of your audience, and I think they appreciate that.”

He was born George Robert Newhart in Oak Park, Illinois, on September 5, 1929. Newhart received his undergraduate degree in management and was employed as an accountant in Chicago. But his heart wasn’t in it. Suppose this nine-to-five corporate drone—someone like Jack Lemmon’s C.C. Baxter in The Apartment—who acted on the side with a local theater, had a penchant for comedy? As Newhart iconically coined it in his classic comedy routines, I think it would go something like this . . .

To relieve the boredom of his workday, Newhart made phone calls to Ed Gallagher, a friend who worked in advertising during which they would improvise characters and comedy bits. They eventually teamed up and recorded them for syndication on radio. The submissions were well received, but the two abandoned their side project when they realized they were losing money.

When his partner accepted a job in New York, Newhart continued to write material with aspirations of becoming a comedy writer. Meanwhile, he took part-time work and pursued a job in radio. A performance of Abe Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue at the local Emmy Awards led to work on a morning TV show for which Newhart supplied comic relief with man-on-the-street interviews. His big break came in 1959, when a local radio star, Don Sorkin, on whose show Newhart first performed Abe Lincoln, recommended him to a friend at Warner Bros. Records.

Newhart’s first album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart, sold more than one million copies. In 1961, it won a Grammy Award for Best Album of the Year, a first for a comedy album, and Newhart also won for Best New Artist, the only time a comedian had been so honored. In 2006, the album was inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry.

The album’s phenomenal success, Newhart said in a 2002 interview, catapulted him to stand-up stardom, even though recording the live album was the first time Newhart had performed his material in front of a nightclub audience. (It reportedly took his manager five months to find a venue—the Tidelands Club at Houston’s Tideland Motor Inn—that would book an unknown comedian). “In one year, I went from doing a man-on-the-street show to six Ed Sullivan shows," Newhart said.

Newhart’s first foray into television was The Bob Newhart Show, a 1961 variety series that lasted one season but was honored with an Emmy and a Peabody Award.

“I probably never should have done it,” he said in a 2015 Huffington Post interview. “I wasn’t seasoned enough. I did a monologue every week . . . and I felt I couldn’t maintain the quality I had achieved on the record album. And they put me in sketches, which I wasn’t very good at.”

He parlayed his recording and nightclub success into appearances on variety and talk shows. He guest-hosted The Tonight Show during the Johnny Carson era almost 90 times.

In 1972, The Bob Newhart Show, a sitcom produced by MTM Enterprises, producers of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, premiered. Newhart starred as Chicago psychologist Robert Hartley, a role that took full advantage of his ability to mine laughs just by listening. Unlike All in the Family, the series rarely tackled the social issues of the day; its humor was primarily character and situational driven. Suzanne Pleschette co-starred as his wife, Emily. At Newhart’s insistence, the couple had no children—he didn’t want to play the hapless or dopey sitcom dad. In the show’s later years, writers submitted a script in which the couple had a baby. Newhart responded by complimenting the writing but then asked, “Who are you going to get to play Bob?”

The show ran for six seasons. In its second year, it was part of CBS’s Saturday night programming block, arguably the greatest lineup in television history: All in the Family, M*A*S*H, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show, and The Carol Burnett Show.

Newhart jokingly revealed the formula for sitcom success to The Huffington Post: “Get great writing and a great cast, and take all the credit yourself.”

He repeated this formula with his next sitcom, Newhart, playing Vermont innkeeper Dick Loudon. This series ran for eight seasons and is best known for its audacious finale in which it was revealed that the entire series was a dream of Dr. Hartley’s. Newhart, in character as his first sitcom protagonist, wakes up in bed next to his former sitcom wife, Pleschette—an idea suggested by Newhart’s wife, Virginia, whom he married in 1963.

In 2002, Newhart received the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. Three years later, he was profiled in the PBS series American Masters. He was had been inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame in 1992, but it was not until 2013 that he received his first-ever acting Emmy in recognition of his guest role as Professor Proton on The Big Bang Theory. He was greeted at the 65th Primetime Emmys with a thunderous standing ovation.

Newhart’s two 1990s TV series, Bob and George and Leo, were each canceled after one season, but he continued to be a welcome guest on such series as ER, The Librarians, and Desperate Housewives.

Movie stardom, however, eluded Newhart. He had a rare leading role as president of the United States in First Family, Buck Henry’s 1980 comedy. His most memorable supporting appearances were in the 1968 caper comedy Hot Millions, Norman Lear’s 1971 satire Cold Turkey, the holiday classic Elf, and Legally Blonde 2: Red, White & Blonde.

And all the while, Newhart continued to do stand-up appearances. “As long as I’m able to,” he told The Huffington Post, “Why stop making people laugh?”

Newhart added that he especially appreciated fans telling him what watching The Bob Newhart Show as a family had meant to them. “That’s one of the great things about being on television,” he said. “You’re part of people’s lives. A man will come up and say that he and his dad watched the show together on Saturday night, and they have this look in their eye, like, ‘What a wonderful time it was.’”

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

October Cover Star Selena Gomez Opens Up: “I Unfortunately Can’t Carry My Own Children”

2024 Presidential Debate Recap: Highlights From the Harris-Trump Showdown

Taylor Swift, “Childless Cat Lady,” Endorses Kamala Harris

Behind the Catholic Right’s Celebrity-Conversion Industrial Complex

Is This the End of Selling Sunset as We Know It?

The 20 Best Fall Movies to Cozy Up With This Season

“Are You Saying No to Elon Musk?”: Scenes From the Twitter Buyout

Inside the Hive Breaks Down the Presidential Debate, the GOP’s Extreme Policies, and More

From the Archive: Meet the Dynamite Socialite Princess TNT of Bavaria