K is a wonder drug. K is addictive. K is transcendental. Beware the K-hole. Matthew Perry drowned in his hot tub while on ketamine.

Six years ago Michael Pollan published How to Change Your Mind, a brain-bending bestseller (made into a recent Netflix series) about how scientists have been using psychedelics to heal depression and mental trauma. For many, the book was a shocker after LSD, magic mushrooms, and MDMA’s half century of being vilified as corruptors of youth—not to mention targets of the “war on drugs” declared by the likes of Richard Nixon and Nancy Reagan. This “war” included an infamous 1987 TV ad that showed a dour man holding an egg and saying: “This is your brain.” He cracks the egg and the insides drop into a hot frying pan. “This is your brain on drugs,” he intones as the egg sizzles.

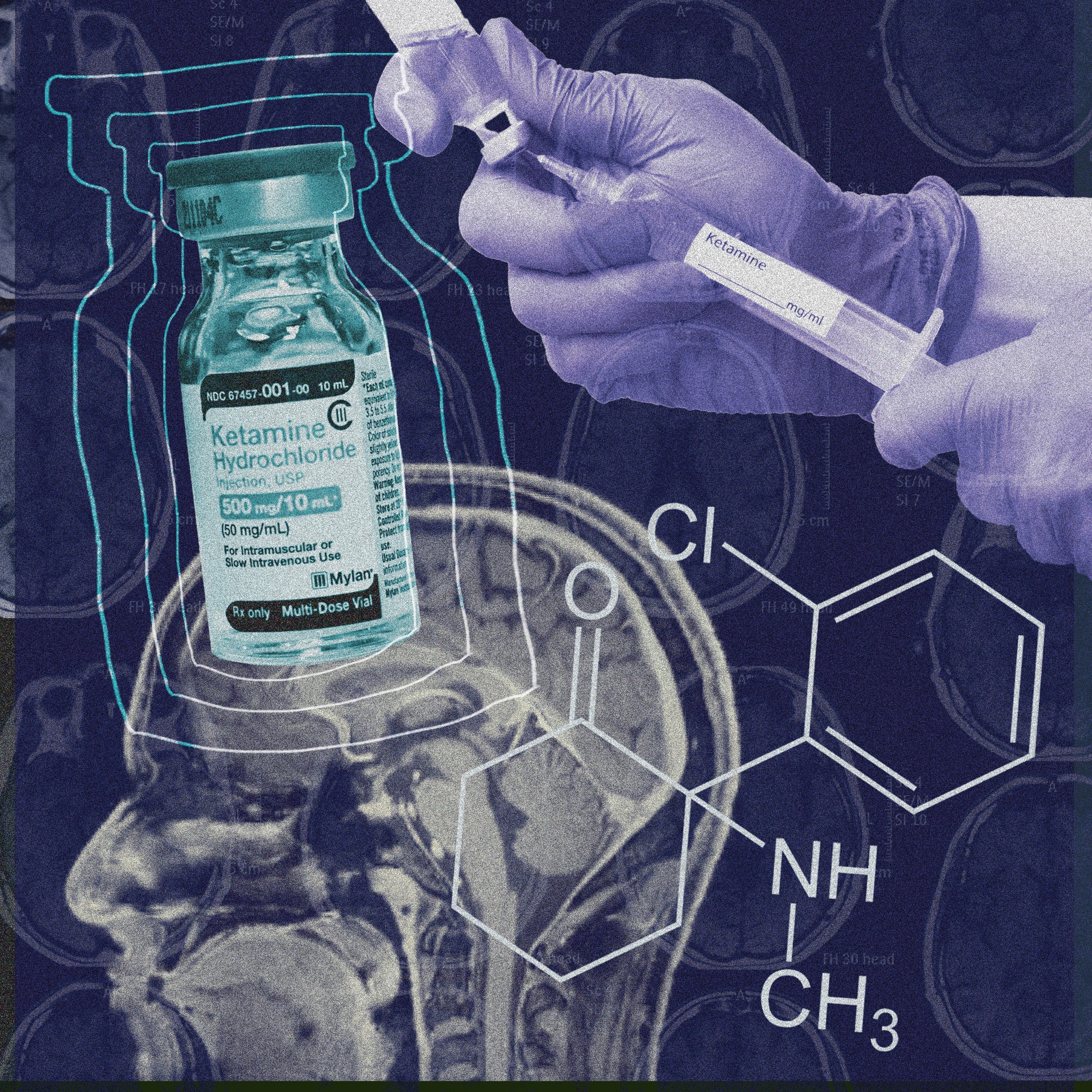

Subtitled What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, Pollan’s book captured a growing movement among psychiatrists, therapists, and scientists around the idea that psychedelics—besides being party drugs—were fast becoming potent remedies to treat various mental maladies. For some patients, they work more quickly and decisively than traditional antidepressants like Prozac, Pollan reported, with fewer troublesome side effects. Ketamine wasn’t mentioned in his book, but he has since written about how it has healing properties similar to those of other psychedelics.

Seemingly overnight, these trippy molecules went from being Nancy Reagan’s worst nightmare to being seen as miracle meds, a trend that accelerated as pandemic lockdowns and viral anxieties clobbered delicate gray matter—including my own—already bruised by the stresses of modern life, including everything from FOMO on social media to climate change to politicians running amok.

Psychedelics changed my mind. Two years ago I wrote an essay for this magazine entitled “Stolen Words: COVID, Ketamine, and Me.” It recounted how I lost my ability to write creatively as long-haul COVID struck me down in 2020, engulfing my mind at times in a pea-soup fog and nudging me into a depression that hampered my ability to write coherently. Ketamine helped rescue me, a surprise for a science writer like me, who has been trained to be skeptical of so-called wonder cures.

My own experience, in effect, became just one of several post-Pollan stories that touted ketamine and other psychedelics for their ability to successfully treat ailing minds while often minimizing side effects. In my article, I tried to be careful to cite the downsides of this powerful drug (that addiction and bad trips were rare but did happen, and that ketamine didn’t work for everyone), even as other firsthand accounts occasionally gushed.

Clinicians also extolled ketamine’s power to patch up brains as the number of K users soared. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and elsewhere ran clinical trials testing ketamine and published mostly positive studies in serious scientific journals like Nature and dozens of others. Entrepreneurs went gaga over K and other psychedelics, launching companies like Atai Life Sciences and Compass Pathways, with some reaching half-a-billion-dollar valuations, while ketamine clinics proliferated.

Now has come the inevitable backlash. Critics in the popular press have piled on with personal stories of addiction and bad trips; and, most notably, the drowning death of Matthew Perry was attributed primarily to the “acute effects of ketamine,” according to the Los Angeles County medical examiner-coroner’s office.

Death by ketamine is extremely rare, but when it happens it can garner media attention. Take the case of a 26-year-old computer programmer in the UK who might have died from an overdose and from complications of having “K-bladder”—a very painful condition involving the destruction of one’s bladder as a result of taking heavy doses of K over a long period of time. Equally disturbing have been police reports of street K being laced with fentanyl, and members of law enforcement using ketamine as an anesthetic to subdue those resisting arrest, some of whom have ended up dead. Among them: Elijah McClain, the 23-year-old Black man in Aurora, Colorado, who was innocently walking home in 2019 when police and paramedics stopped him and injected a lethal 500 mg dose of ketamine.

Ketamine prescriptions by Zoom are proliferating, with online companies providing the drug in the mail after a quick telemedicine visit. The unsupervised oral ingestion of K, usually at home, was recently blasted by the FDA when it issued a warning about the risks of using compounded K lozenges without supervision. Scientific journals like the Journal of the American Medical Association have also run stories about false and misleading ads proffered by some ketamine clinics and companies. And just a few weeks ago, misgivings about another psychedelic led an FDA-convened advisory panel of independent experts to advise the agency to deny approval of an MDMA-aided treatment to help those suffering from PTSD.

The upshot of all of this has been calls to better regulate ketamine and to establish a more stringent set of standards for its safe use.

Adding to the current muddle about ketamine is an ongoing debate between traditional scientists and clinicians (who believe that ketamine’s hallucinations and “dissociative episodes” are an unwanted side effect for a medicine that seems to work mechanistically in the brain, with or without transcendent experiences) and some of their counterparts, who believe that the trips, good or bad, used in combination with “talk therapy,” are critical to a patient’s thorough healing.

“I don’t consider ketamine a psychedelic,” insists Glen Brooks, an anesthesiologist and the founder and clinical director of NY Ketamine Infusions, a string of clinics in and around New York City that provide ketamine delivered through an IV in a procedure that does not involve talk therapy. “It kind of flies into the basic science of how ketamine works mechanistically in the brain.” Sitting in his office near Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, Brooks points to a framed illustration on his wall from a 2010 study that shows how one dose of K caused damaged dendrites in the frontal cortices of depressed rats to literally regrow—something that certain scientists believe also happens in depressed people who take K. In Brooks’s view, ketamine is not a mind expander, but a tool for mind healing.

Counterpoised to Brooks and his peers is another camp that uses ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP), administering a dose of psychotherapy before a hit of K. (Ketamine journeys last only about an hour, while those of other psychedelics last many; K is also legal, approved by the FDA as an anesthetic that doctors prescribe off-label as an antidepressant.) After the trip, clinician and patient talk some more, integrating what was experienced: weird colors, floating in outer space, chats with dead people, whatever. KAP practitioners contend that the talk and the visions are key to a lasting and meaningful treatment.

“We are treating the emotions and psychiatric needs of a patient along with what the medicine is doing inside the brain,” says Phil Wolfson, a psychiatrist and researcher based in San Anselmo, California. He is the coauthor of The Ketamine Papers and heads the Ketamine Research Foundation, which teaches caregivers how to use KAP. “Just administering the drug with no counseling or discussion can be confusing, given the psychedelic experiences, and it doesn’t always address underlying emotional issues contributing to a person’s depression,” adds Wolfson, who cites studies that support KAP, although he admits that more research is needed to fully understand how KAP works.

In 2020, when I used ketamine to recover my words and my brain, I went to Wolfson and personally found great value in the KAP approach. My initial journey and hallucinations—along with Wolfson’s guidance, using KAP—were transformative for me. The most critical scene in my journey involved a character in a novel that I was writing at the time appearing in a hallucination and telling me that everything was going to be okay.

I have not tried Brooks’s method. An earnest, white-haired man with a caring and empathetic demeanor, he allowed me to peek into one of his infusion rooms during my visit to his clinic. Unlike Wolfson, who administers KAP in a cozy office with zen-like decor, transcendental music, and discussions of intentionality in what he calls a “conducive setting,” Brooks’s infusion spaces are more like classic clinic exam rooms, replete with an IV to administer the drug and machines to keep track of vitals. He dismisses the idea that talk therapy or spiritual music is necessary. “I don’t want patients to put on some meditation tape or some silly flute music or something,” he says, “which isn’t going to affect the outcome. What I tell our patients is, ‘You’re really a passive passenger.’”

Wolfson disagrees, although both physicians maintain that ketamine has worked for thousands of their patients. They agree that science seems to support the drug’s basic use as both an antidepressant and a means for reducing anxiety and pain. They also emphasize the need to tell patients about the downsides of ketamine, and each has stories of patients having the occasional bad trip, as well as a handful harboring addictive tendencies. Wolfson and colleagues recently wrote a statement underscoring K’s potential dangers, but also its benefits in a KAP setting—a response, he says, to the recent backlash.

What’s missing in this discussion are the large, long-term studies of how ketamine impacts users, including risky side effects. They would go a long way in countering the hype-and-backlash cycle that, in the absence of long-term research, exists in a kind of information vacuum. These are the sorts of longitudinal studies that modern medicine doesn’t tend to pay for when a drug is generic—as most psychedelics are—and won’t generate the huge profits that patented meds generate; or when an off-patent drug has already been approved for treating another condition. Indeed, reforms are needed in the overall drug-testing model, changes that focus on what happens to the body and brain, holistically, over time (think Ozempic).

Ramped-up research would also help shape protocols for administering ketamine more safely and humanely; tamp down alarmist rhetoric; and serve to ensure that this potent medicine and other psychedelics are used to help people and stanch abuse. “In the end,” says Brooks, “I’m for anything that works, as long as it’s safe”—a sentiment Wolfson says he shares. So do, I suspect, most of the ketamine backlashers.

David Ewing Duncan is a contributor to Vanity Fair and a best-selling author and science journalist.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

DNC 2024: Live Updates From the Democratic National Convention

September Cover Star Jenna Ortega Is Settling Into Fame

Listen Now: VF’s DYNASTY Podcast Explores the Royals’ Most Challenging Year

Exclusive: How Saturday Night Captures SNL’s Wild Opening Night

Inside Prince Harry’s Final Showdown With the Murdoch Empire

The Twisted True Love Story of a Diamond Heiress and a Reality Star