To receive the Vogue Business China Edit, sign up here.

Chinese consumers are the world’s biggest buyers of fur, but some are beginning to ask questions and rethink their support of the trade, according to an exclusive Vogue Business survey.

Fur producers have already faced a torrid 2020 as Covid-19 outbreaks on mink farms decimated breeding stocks and Western governments ramped up legislation against fur production and even sales. Denmark, which exports the most mink of any European country, effectively closed its fur trade by culling up to 17 million of the animals last autumn. The Dutch government brought forward a 2024 ban on mink fur breeding to this year, while France said there would be no more production from 2025. The UK, meanwhile, is considering joining California in banning the sale of new fur products.

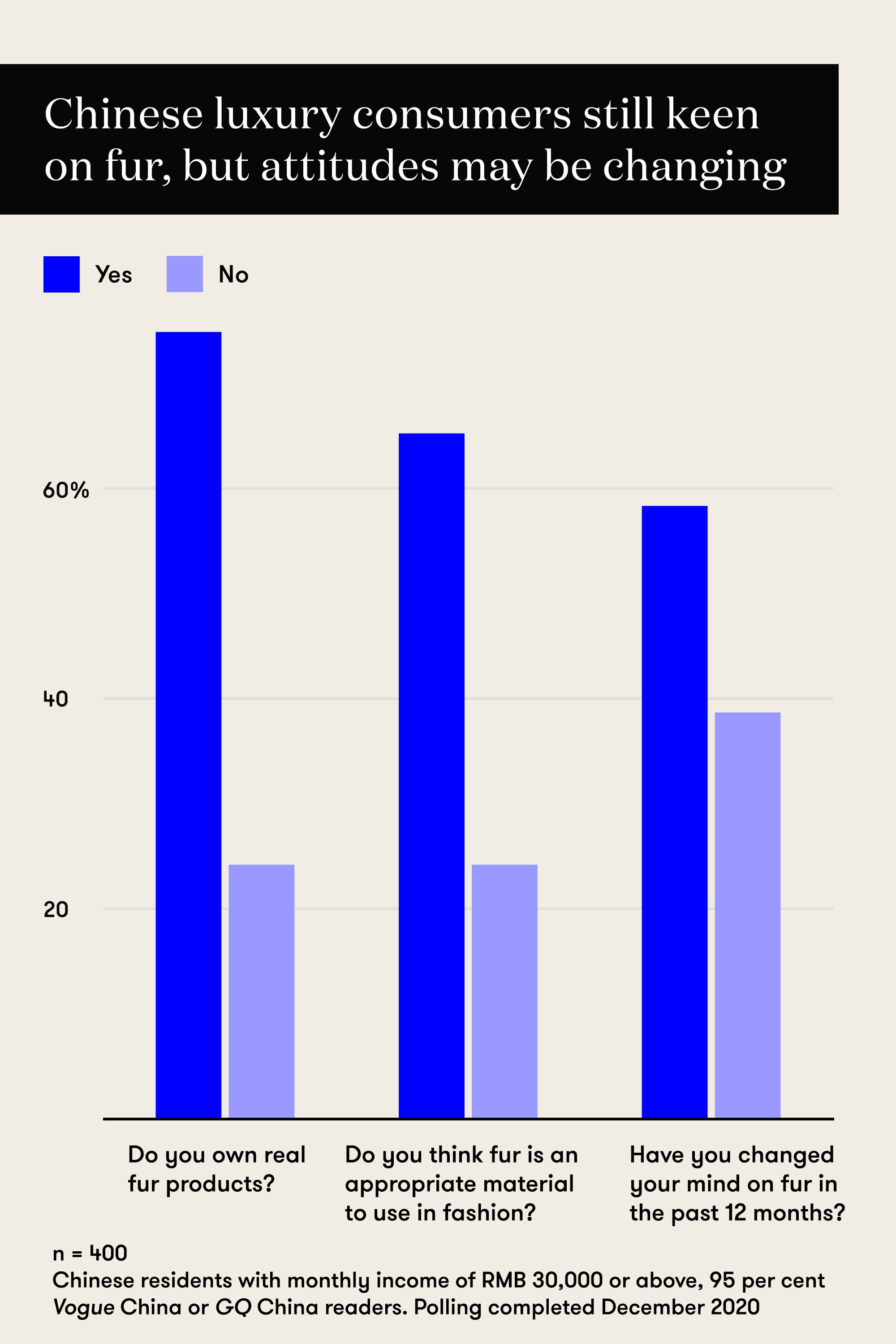

For those luxury brands that are continuing to use fur, the focus is on China, the country most important to the $22 billion worldwide fur trade. A survey of 400 high-income Chinese residents, predominantly Vogue and GQ readers, by Vogue Business and market research group Dynata, shows that demand for fur in China is likely to remain robust for now — but there are some signs of disquiet among a minority of fur buyers.

Just under two-thirds of respondents say they believe that fur is an appropriate material to use for clothing versus 24 per cent that think it is not. Of the group that say fur is an inappropriate material, 62 per cent say they have changed their mind in the last year — and just under half have previously purchased fur products. Objections are not necessarily based on ethical considerations, but also embrace factors such as taste and practicality.

Younger consumers appear to be leading the shift in attitude. “I think that in the Western world there’s a feeling that China is backward [on environmental issues] and that might have been true 20 years ago, maybe even 10 years ago, but right now the younger consumers are really into morality,” says Shaun Rein, founder and managing director of the China Market Research Group, which works with luxury clients including Richemont. Rein says that animal welfare is a growing concern among Chinese consumers. However, fur has been a lower priority target than shark fin or ivory.

In the West, demand for mink fur as a material was on the decline before the ongoing Covid-19 related challenges and government bans. Nordstrom became the latest luxury business to ban sales of the material in September, joining Versace, Gucci, Farfetch, Giorgio Armani and Tommy Hilfiger. Reflecting excess supply, prices have declined from a high of €59 per mink pelt in December 2013 to just €19 in September 2020, per Kopenhagen Fur data, putting pressure on farmers.

These falling prices for European fur may be to the benefit of companies targeting the Chinese market. Sofya Bakhta, China market analyst at Daxue Consulting, says that 2019 saw Singles Day sales for fur top RMB 100 million, a 10 per cent rise on the year before. “[Fur coats] are often given as lavish gifts,” notes Bakhta. Fears of a depleted supply of European furs, generally viewed to be of a higher quality than those made in China, appear to have reversed the decline in prices of pelts in the short term. Magnus Ljung, CEO of Finnish auction house Saga Furs, notes a jump in pelt prices for Saga Furs’ December auctions, but an additional increase of 20 to 30 per cent is required to make all breeders profitable. He is confident that prices will strengthen further over the coming year.

A key trend in China has been a move away from full fur coats to fur-lined items and accessories, says Su. The fur-lined parkas of Canada Goose are popular, with the brand’s direct sales surging in Mainland China by 30 per cent in the last quarter. Animal welfare group ActAsia notes that a standard fur-trimmed and -lined parka coat can now be bought for as little as $100-150 in China, “making the purchase a perceived bargain for the consumer”.

LVMH and Kering both recognise Furmark, a programme developed by the International Fur Federation (IFF) that brings animal welfare and sustainability certifications from Europe, the US, Canada, Russia and Namibia under one umbrella. Chinese farms are not yet included in the scheme.

Louis Vuitton CEO Michael Burke told Il Sole 24 Ore last autumn that the brand has no plans to abandon the use of fur or exotic skins, citing the ethical certifications the brand has in place on the farms it uses, the practicability of the materials and the centuries of craftsmanship utilising them.

The continued support for fur by brands like Louis Vuitton remains important to the fur industry and its image to Chinese buyers, even if sales by luxury brands account for a small share of the overall retail trade in fur. Rein says he is doubtful that luxury consumers in China would care much whether they are buying real or faux fur, as long as the product is from a name they trust. “They care more about the luxury brand than they do about the actual ingredients,” he says.

What propelled most government bans in Europe in 2020 was the fear that transmission of Covid-19 between humans and mink could make human vaccines less effective (although the data thus far suggests that this is probably not true). The University of Helsinki and the Finnish Fur Breeders’ Association announced last Tuesday that work is advanced on a vaccine for mink and finn raccoon. Mark Oaten, CEO of IFF, says that the vaccine is a potential game changer that can help to unlock funds from lenders for farmers looking to expand their production to cover the drop in supply caused by the Danish cull.

The link between mink and the virus has not been a big concern among the Chinese buying public, says ActAsia founder Pei Su. “Whatever happened in Europe seems to be far away,” she says, claiming that further Covid-19-type outbreaks are likely, even with a vaccine.

The Chinese government temporarily banned wildlife trading when the pandemic broke out, but lifted the restrictions for fur in April last year. Chinese fur traders benefited from rising prices after the Danish cull, with traders quoted by Reuters saying that the government was offering free mink virus tests for larger farms, subject to strict hygiene protocols.

China consumers’ growing interest in environmental concerns, particularly among the young, represents a long-term challenge for the fur industry. But Oaten points out that fur is a plastic-free product that is more environmentally friendly than faux-fur alternatives. “Our challenge is to say, look, it is a luxury, but it’s also sustainable,” he argues. “It’s not something that you throw away every year. It is actually a natural product.”

To receive the Vogue Business newsletter, sign up here.

Comments, questions or feedback? Email us at feedback@voguebusiness.com.

More from this author:

Could luxury travel bounce back first?

Leading luxury brands more dominant than ever, says Deloitte