British mosques explored: 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale preview

Previewing the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, we catch up with Shahed Saleem, one of the curators at the Applied Arts Pavilion Special Project. Titled ‘Three British Mosques', this exciting collaboration between La Biennale di Venezia and London's Victoria & Albert Museum focuses on adapted mosque spaces in London

With the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale launch approaching, we catch up with author and architect Shahed Saleem, one of the curators at the Applied Arts Pavilion Special Project, a collaboration between La Biennale di Venezia and London's Victoria & Albert Museum. The project, which will be part of the Arsenale displays, is titled ‘Three British Mosques', and looks into ‘contemporary multiculturalism through three adapted mosque spaces in London'. Our discussion spans from religious spaces to visitor experience at the display, which is set to open on 22 May in Venice.

W*: Tell us about this year's special V&A project at the biennale. What attracted you to explore this particular theme?

Shahed Saleem: I've been studying and designing mosques in Britain for over a decade, so when the V&A approached me to develop my work into an exhibition for the biennale, it seemed a meaningful response to this year’s theme of ‘How will we live together?’, because it is about how different cultures and communities can coexist side by side.

W*: How did you choose your three case studies?

SS: Mosques in Britain are mostly created through the adaptation of existing buildings, and these three case studies exemplify this.

The house-mosque is the simplest form of mosque, where domestic space is altered to become religious, and this is vividly illustrated in the Harrow Mosque. Many of the earliest mosques were made from houses, as they were the easiest type of building to acquire. Historically, many other minority religious communities in Britain created their first places of worship from house conversions, such as Nonconformists and Jews a hundred years previously. So the house mosque is a continuation of this tradition.

Brick Lane Mosque represents the re-use of a former religious building. Again, many mosques have been made in this way, as religious space lends itself to easy re-use for Muslim worship. Brick Lane Mosque has a unique religious history: it was built as a Protestant Church, was then a Methodist chapel, followed by a synagogue, before it became a mosque. It shows how religious uses can layer themselves into one architectural space.

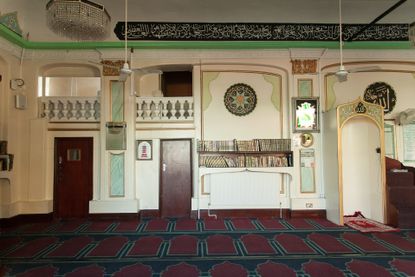

Old Kent Road Mosque was a former pub. It shows how the existing decoration and features of the pub have been adapted to become part of the mosque language. This combination of aesthetics and styles is a feature of adapted mosque buildings, where a new Islamic visual language emerges through the hybridisation of cultural references.

Image depicting the Harrow Mosque

W*: What attracts you to an adapted mosque structure like your case studies? What excites you in this type of mosque?

SS: These buildings are mostly self-designed, and in many cases self-built by the community who have established them. The design decisions are often rooted in the memories and visual culture of these communities. The design process is often ad hoc and collaborative, so it's a very democratic process with decisions made as the work progresses. The needs of the mosque are also continuously changing as the community grows and evolves. So this type of architecture is quite organic and improvised, and highly responsive to the needs and emotions of the community that uses it. I find this very exciting as it throws up new and unexpected design juxtapositions, and new symbolic and architectural meanings.

W*: Assuming adapted mosques are not unique to the UK, are there any international examples that really stand out to you?

SS: Adapted mosques are characteristic of the Muslim diaspora in Western countries, so you see them as the main mosque typology across northern Europe and the US. I find that some of the most striking are in former religious buildings or large spaces. One that stands out in my mind is the Fatih Mosque in Amsterdam, set in an imposing and elegant brick former Catholic church dating from the 1920s.

W*: What would you like the visitor to take away from the exhibition?

SS: I'd like the visitor to feel that they have gained a familiarity with the mosque and have physically engaged with these buildings. Through this I hope that people can further appreciate the inventiveness and richness of the architectural and aesthetic decisions that the mosque congregations have made in the creation of these unique places of worship.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Interior detail of Old Kent Road Mosque

Mihrab at Harrow Mosque, set in a converted house

Men's prayer hall at the Brick Lane Mosque, a building that has been adapted for use by various faiths over time

INFORMATION

‘Three British Mosques’, Sale d’Armi A, Arsenale, 22 May – 21 November 2021

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

The best design-led cocktail shakers

The best design-led cocktail shakersIf you like your drinks shaken not stirred, these are the best cocktail shakers to take your mixology skills to the next level

By Rosie Conroy Published

-

Tech Editor, Jonathan Bell, selects six new and notable Bluetooth speaker designs, big, small and illuminating

Tech Editor, Jonathan Bell, selects six new and notable Bluetooth speaker designs, big, small and illuminatingThese six wireless speakers signal new creative partnerships and innovative tech approaches in a variety of scales and styles

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

As London’s V&A spotlights Mughal-era design, Santi Jewels tells of its enduring relevance

As London’s V&A spotlights Mughal-era design, Santi Jewels tells of its enduring relevance‘The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence’ is about to open at London’s V&A. Here, Mughal jewellery expert and Santi Jewels founder Krishna Choudhary tells us of the influence the dynasty holds today

By Hannah Silver Published

-

A new village chapel in the Czech Republic is rich in material and visual symbolism

A new village chapel in the Czech Republic is rich in material and visual symbolismStudio RCNKSK has completed a new chapel - the decade-long project of Our Lady of Sorrows in Nesvačilka, South Moravia

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Venice Architecture Biennale 2025: a glimpse of what’s to come and Carlo Ratti's circular economy manifesto

Venice Architecture Biennale 2025: a glimpse of what’s to come and Carlo Ratti's circular economy manifestoVenice Architecture Biennale 2025 curator Carlo Ratti talks about the theme, 'Intelligens' and launches his circular economy manifesto; the first glimpses into what’s to come at the festival's launch next spring

By Ellie Stathaki Last updated

-

A contemporary Istanbul mosque offers a take on tradition

A contemporary Istanbul mosque offers a take on traditionTurkey's Degostudio crafts this Istanbul mosque as a new, functional space for worship with accessible facilities

By Feride Yalav-Heckeroth Published

-

Giovanni Michelucci’s dramatic concrete church in the Italian Dolomites

Giovanni Michelucci’s dramatic concrete church in the Italian DolomitesGiovanni Michelucci’s concrete Church of Santa Maria Immacolata in the Italian Dolomites is a reverently uplifting memorial to the victims of a local disaster

By Jonathan Glancey Published

-

‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’ at the V&A is a bold exploration

‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’ at the V&A is a bold explorationLondon’s V&A presents ‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’, a deep dive into 1940s architectural influences within West Africa and India

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

The modernist First Christian Church celebrates its iconic tower’s restoration in Columbus

The modernist First Christian Church celebrates its iconic tower’s restoration in ColumbusThe modernist First Christian Church in Columbus, Indiana, designed by Eliel and Eero Saarinen, has completed extensive restoration works on its iconic tower

By Audrey Henderson Published

-

Carlo Ratti announced curator of Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

Carlo Ratti announced curator of Venice Architecture Biennale 2025Carlo Ratti has been revealed as the Director of the Architecture Department at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, with the specific task of curating the 19th International Architecture Exhibition

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Behind the V&A East Museum’s pleated façade

Behind the V&A East Museum’s pleated façadeBehind the new V&A East Museum’s intricate façade is a space for the imagination to unfold

By Ellie Stathaki Published