London show celebrates the male physique in photography, from muscle hunks to scruffy punks

‘A Hard Man is Good to Find!’ – newly open at London’s Photographers’ Gallery – is a delectable survey of queer photographs of the male body created in London between the 1930s and early 1990s

At The Photographers’ Gallery, London, male-physique lovers can have their beefcake and eat it too. Dishing up more than a hundred photographs – in addition to magazines, personal albums and photo sheets – the exhibition ‘A Hard Man is Good to Find!’ is a feast for the eyes.

Titled after American actress Mae West’s famous quote, the exhibition spans 60 years of queer image-making, from svelte bathers to muscle hunks and scruffy punks. It is divided into half a dozen sections, which map out subcultural territories of the British capital, from Hampstead Heath to Portobello and Euston.

‘In the early part of the 20th century, homosexuality was illegal,’ the exhibition curator Alistair O’Neill notes as we walk through the gallery’s baby-pink walls. Despite the 1955 Wolfenden Report – which recommended the depenalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults – and the subsequent 1967 Sexual Offences Act – which marked the partial decriminalisation of gay sex – Britain’s obscenity laws remained a considerable obstacle for the production of homoerotic imagery. ‘Representations of the male nude came under considerable scrutiny and the ability for queer men to look at other men in states of undress was fairly limited,’ continues O’Neill, who teaches Fashion History and Theory at London’s Central Saint Martins.

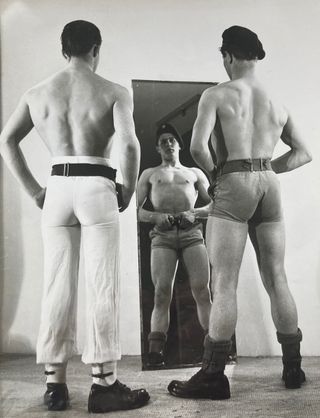

Angus McBean, David Dulak, 1946

The exhibition starts strongly with a rarely seen collage series by British painter Keith Vaughan, dated from 1933. It features cut-out photographs of thong-wearing sunbathers taken by the then-21-year-old artist at Highgate Men’s Pond. Superposed with textual elements over monochromatic olive-green backgrounds, the images are compiled in a diary-style photobook that is on display behind a glass cabinet, while enlarged prints of individual pages are reproduced on a wall.

‘He’d just purchased a Leica camera and turned his bedroom in his mother’s house in West Hampstead into his dark room,’ O’Neill recounts. ‘He wouldn’t have been able to print these commercially because of the nature of the images.’ At once scenic and suggestive, they play with contrast and repetition in remarkably modernist ways that prefigure elements of Richard Hamilton’s early Pop Art. Interestingly, the presence of jockstraps in the photographs suggests that the famed undergarment did not become a gay symbol in 1950s America with the advent of magazines such as Physique Pictorial, as is often assumed. (For fans of the latter, a rare posing pouch lovingly crafted by its publisher Bob Mizer’s mother is on display in the adjacent annexe room.)

Basil Clavering, (Royale, Hussar, Dolphin). Mail order Storyette print, late 1950s

It’s not all about sex: many works in the show are imbued with an irresistible camp quality, too. Chief among them, the 1950s ‘storyettes’ – catalogue photo sheets assembled into a narrative – demonstrate their makers’ imaginative use of humour. Conceived to discreetly advertise erotic prints to order by mail, storyettes were initiated by sailor-turned-cinema owner Basil Clavering from his basement studio in Pimlico. To avoid scrutiny, Clavering assembled the images like film stills, orchestrating comical scenarios in which military men are seen progressively undressing, flexing their muscles in front of a mirror and eventually ironing each other’s uniforms in the nude. ‘It’s kind of seaside postcard humour,’ O’Neill laughs, ‘or like a drag pantomime.’

At times, the exhibition’s desire to illustrate one community’s efforts to produce and circulate radical images eclipses critical issues such as consent and exploitation. For instance, 1930s erotic images of working-class guardsmen exchanging sex and consumerist pleasures for money; street and intimate portraits of 1980s punks catfished in the streets of King’s Cross under the pretence of a false Vogue campaign, and lists of models’ names categorised by race all point to complex power dynamics that the show does little to address or contextualise.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Martin Spenceley, 1980s

Thankfully, the final display brings some much-needed nuance to this narrative with a glimpse into the Brixton Art Gallery’s development. Opened in 1983 under a railway arch, it was run by an artist collective including the likes of Ajamu X, Franko B and Guy Burch, whose queer and intersectional work was largely excluded from mainstream exhibition spaces. One arresting portrait by the late Nigerian photographer Rotimi Fani-Kayode – a prominent figure of the Black British Art scene and founding member of the activist art organisation Autograph – shows a Black nude model gazing at the camera through a Venetian long nose mask, his genitals covered in gold paint. Titled The Golden Phallus, the work was made in 1989 to address colonial stereotypes in the climate of the Aids crisis, namely Robert Mapplethorpe’s fetishist depiction of Black male nudes.

‘A Hard Man is Good to Find!’ is a delectable show that compellingly traces the proliferation of an otherwise undermined visual subculture. Enjoy it while it’s hot.

‘A Hard Man is Good to Find!’, until 11 June 2023, The Photographers' Gallery, London. thephotographersgallery.org.uk

-

‘There are hidden things out there, we just need to look’: Studiomama's stone animals have quirky charm

‘There are hidden things out there, we just need to look’: Studiomama's stone animals have quirky charmStudiomama founder's Nina Tolstrup and Jack Mama sieve the sands of Kent hunting down playful animal shaped stones for their latest collection

By Ali Morris Published

-

Tokyo firm Built By Legends gives fresh life to a performance icon, Nissan’s R34 GT-R

Tokyo firm Built By Legends gives fresh life to a performance icon, Nissan’s R34 GT-RThis Japanese restomod brings upgrades and enhancements to the Nissan R34 GT-R, ensuring the cult of the Skyline stays forever renewed

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Squire & Partners' radical restructure: 'There are a lot of different ways up the firm to partnership'

Squire & Partners' radical restructure: 'There are a lot of different ways up the firm to partnership'Squire & Partners announces a radical restructure; we talk to the late founder Michael Squire's son, senior partner Henry Squire, about the practice's new senior leadership group, its next steps and how architecture can move on from 'single leader culture'

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Doc'n Roll Film Festival makes its loud return to the UK

Doc'n Roll Film Festival makes its loud return to the UKThe 11th edition of the Doc'n Roll Film Festival celebrates music, culture and cinema from around the world

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Preview the Jameel Prize exhibition, coming to London's V&A, with a focus on moving image and digital media

Preview the Jameel Prize exhibition, coming to London's V&A, with a focus on moving image and digital mediaThe winner of the V&A and Art Jameel’s seventh international award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition will be showcased alongside shortlisted artists

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Genesis Belanger is seduced by the real and the fake in London

Genesis Belanger is seduced by the real and the fake in LondonSculptor Genesis Belanger’s solo show, ‘In the Right Conditions We Are Indistinguishable’, is open at Pace, London

By Emily Steer Published

-

Francis Bacon at the National Portrait Gallery is an emotional tour de force

Francis Bacon at the National Portrait Gallery is an emotional tour de force‘Francis Bacon: Human Presence’ at the National Portrait Gallery in London puts the spotlight on Bacon's portraiture

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s ParkTwenty-two international artists turn the English gardens into a dream-like landscape and remind us of our inextricable connection to the natural world

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Meet Oluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, the founders creating a new art community

Meet Oluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, the founders creating a new art communityOluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, are behind Piece Unique, an artist agency that guides and future-proofs emerging artists’ careers

By Mazzi Odu Published

-

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024As the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair returns to London (10-13 October 2024), here are the artists to see

By Gameli Hamelo Published

-

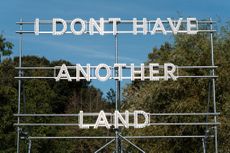

Es Devlin’s large-scale choral installation celebrates London’s displaced population

Es Devlin’s large-scale choral installation celebrates London’s displaced populationEs Devlin has partnered with UK for UNHCR on a free and open-to-all exhibition, ‘Congregation’, in London from 3-9 October 2024

By Hannah Silver Published