- Anglo-Saxon England

- 18th-century Britain, 1714–1815

- Britain from 1914 to the present

Walpole’s loss of power

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

News •

Walpole’s luck and political grasp only began to fail in 1737. In that year Queen Caroline, one of his most important allies, died. At this time, too, Frederick Louis, prince of Wales, George II’s eldest son and heir apparent, followed Hanoverian family tradition; he quarreled with his father and aligned himself with the Opposition. This damaged Walpole’s position in two ways. The king, born in 1683, was now in his 50s, which was elderly by the standards of the time. Many young ambitious MPs, such as William Pitt, were inclined to join Prince Frederick, because they saw in him the political future. Moreover, as Prince of Wales, Frederick owned a large part of the county of Cornwall and consequently controlled numerous rotten boroughs. In the 1734 election the Cornish constituencies had returned 32 pro-government MPs to Parliament; but at the next general election in 1741, when Prince Frederick used his electoral influence against Walpole, only 17 pro-government candidates were returned by this county. Walpole lost another important ally to the opposition, John, duke of Argyll. Argyll was a member of the Cabinet, the most important Whig landowner in Scotland, and head of Clan Campbell. In the 1734 election his influence in Scotland helped to ensure that 34 of the country’s 45 elected MPs were pro-government. But by the 1741 election he had defected to the Opposition, and the electoral repercussions were serious. On this occasion Scottish constituencies only elected 17 pro-government MPs.

But Walpole’s main enemies were time and war. By 1737 he was in his 60s and had dominated politics for 15 years. Some ambitious Whigs resented his prolonged monopoly on power; others anticipated his retirement or death and judged it prudent to distance themselves from his administration. And some of Walpole’s policies were now widely viewed as dubious, even anachronistic. Whereas he wanted to keep Britain out of war, many government and Opposition MPs, and even some members of Walpole’s own Cabinet, favoured going to war with Spain to gain colonial and commercial objectives. Such a war policy was strongly backed by commercial opinion in London and in the nation’s main trading cities.

It was a sign of Walpole’s declining powers that he was unable to prevent the drift into war in 1739. The War of Jenkins’ Ear (so called after an alleged Spanish atrocity against a British merchant navy officer, Captain Robert Jenkins) was initially successful. Admiral Edward Vernon became a popular and Opposition hero when he captured the Spanish settlement of Portobelo (in what is now Panama) in November 1739. But his victory was followed by several defeats, and Britain soon became embroiled in a wider European conflict, the War of the Austrian Succession. Walpole survived the general election of 1741, but with a greatly reduced majority. His political doom was sealed in the fall of that year when the Tory and Whig sectors of the Opposition managed finally to agree on a strategy to defeat him. Walpole eventually resigned from his offices in early 1742. He still retained the king’s favour, and, although sections of the Opposition wanted to impeach him for corruption, he was given a peerage, entered the House of Lords as earl of Orford, and died in his bed in 1745. Nonetheless, the fact that he had to resign despite George II’s continuing support indicated an important development in the British political system. Although monarchs retained the rights to choose their own ministers, they could no longer retain a chief minister who was unable to command a majority of votes in the House of Commons. If they wanted to remain in office, chief ministers now needed to possess parliamentary as well as royal support.

Britain from 1742 to 1754

Political events after Walpole’s resignation demonstrated once again the artificiality and inner tensions of the Opposition. Its Tory sector (some 140 MPs strong) had expected that a new administration would be formed in which some of their leaders would be given state office. They hoped that the proscription of their party, implemented after 1714, would be reversed and that various changes in domestic and foreign policy would be made. But now that Walpole was out of the picture many of their Patriot Whig allies wanted nothing more to do with Tories or Tory measures. The leading Patriot Whig, William Pulteney, accepted a peerage and became earl of Bath. Six other Patriot Whigs accepted government office, including John, Baron Carteret (later earl of Granville), who became the new secretary of state. Spencer Compton, now earl of Wilmington, became the new first lord of the treasury and nominal head of the government. Fourteen former members of Walpole’s administration retained their posts, including Henry Pelham and his older brother, Thomas Pelham-Holles, duke of Newcastle. The Tories, as well as many people outside Parliament, had expected the fall of Walpole to result in a revolution in government and society, but this did not occur. Instead, all that had happened was a reshuffling of state employment among patrician Whigs, which caused widespread disillusionment and anger. It was with the Patriot Whigs in mind that Samuel Johnson, a staunch Tory, was later to describe patriotism in his Dictionary as the last resort of the scoundrel.

When Wilmington died in 1743, Carteret took over as head of the administration. He was a clever and subtle man, able to speak many European languages, and fascinated by foreign affairs. These qualities naturally endeared him to the king. His status as a royal favourite was confirmed when he accompanied George on a military expedition to Germany in defense of the electorate of Hanover. In June George commanded his British and Hanoverian troops at the Battle of Dettingen (the last battle in which a British monarch commanded), defeating the opposing French forces. But the victory was not followed up and aroused little patriotic enthusiasm in Britain. Instead, accusations that the king and Carteret were sacrificing British interests to Hanoverian priorities were openly expressed in Parliament and in the press. The Pelham brothers took advantage of this discontent (and Carteret’s absence) to undermine his political position. In November 1744 he was forced to resign, though during the next 18 months George II continued to consult with him privately on political business. These intrigues infuriated Henry Pelham, who was now first lord of the treasury and chancellor of the exchequer, and his brother Newcastle, who was secretary of state.

The Jacobite rebellion

Britain’s involvement in the War of the Austrian Succession, Tory and popular anger at the political deals that followed Walpole’s resignation, and the infighting among the Whig elite were the background to the Jacobite rebellion of 1745–46 (the Forty-five). Since Britain was now at odds with France, the latter power was willing to sponsor an invasion on behalf of the Stuart dynasty. It hoped that such an invasion would win support from the masses and from the Tory sector of the landed class. Although a handful of Tory conspirators encouraged these hopes, the degree of their commitment is open to question. A large-scale French naval invasion of Britain in early 1744 failed in part because these men would not commit themselves to action. In July 1745 the Old Pretender’s eldest son, Charles Edward Stuart (the Young Pretender), landed in Scotland without substantial French aid. In September he and some 2,500 Scottish supporters defeated a British force of the same size at the Battle of Prestonpans. In December, with an army of 5,000 men, he marched into England and got as far south as the town of Derby, some 150 miles from London.

Charles’s initial success owed much to the ineptitude, the unconcern even, of Britain’s rulers. One problem was that the standing army was too small, consisting of some 62,000 men. Because of Britain’s involvement in the War of the Austrian Succession, the bulk of this force was in Flanders and Germany. Only 4,000 men had been left to defend Scotland, and most of them were raw recruits. Moreover, hampered by internal divisions, the administration was slow to respond. When the Young Pretender landed, the Pelhams were anxious but Carteret, now earl of Granville, was not. Nor, at the beginning, was George II, who was actually in Hanover when his rival for the throne landed. As a result of these squabbles and misunderstandings, Parliament did not assemble until October 17, 1745. Because by law only Parliament could authorize money to pay the militia (Britain’s civil defense force), this delay seriously impeded early resistance to the Jacobite force. The city of Carlisle in the north of England surrendered to the rebels in November largely because its militia had received no pay from the government or from anyone else for two months.

Some historians have argued that the mass of Britain’s population cared little which dynasty ruled them at this time and that the Young Pretender would have regained the kingdom for the Stuarts if only he had pressed on to London. Clearly, this thesis can never be proved one way or the other. The Jacobites, however, did not try to march on to London but retreated to Scotland. Nonetheless, it is probably significant that the Young Pretender attracted scarcely any English supporters on his march to Derby. Only in Manchester, which had a large Catholic population, did he gain recruits—some 200 men, mostly unemployed weavers. No Tory landowner or politician joined him, nor did any men of influence or wealth come out in his favour. By contrast, once the seriousness of the invasion was recognized, many individuals joined home-defense units or subscribed money against it. Between September and December 57 civilian loyal associations are known to have been founded in 38 different counties. Merchants and traders in the prosperous towns—Liverpool, Norwich, Exeter, Bristol, and most of all London—were particularly prominent in loyalist activity.

Although many Britons had become disillusioned by events after Walpole’s fall, probably few were seriously tempted by the prospect of a Jacobite restoration. The Young Pretender, a Roman Catholic, was viewed as the pawn of France, Britain’s enemy and prime commercial and imperial competitor. Traditionally the Catholic religion and French politics were associated with absolutist government, religious persecution, and assaults on liberty. These prejudices worked against the Young Pretender’s appeal, as did prejudices against the Scottish Highlanders, the bulk of his armed supporters, who were regarded as terrifying barbarians by many of the English. The lack of mass English support for the Stuarts in 1745 dissuaded the French government from sending substantial military aid to the rebels. On April 16, 1746, the duke of Cumberland (George II’s second son) defeated the Jacobite army at Culloden in northern Scotland. This was the last major land battle to occur in Great Britain. The Young Pretender escaped to France and finally died in 1788, sodden with drink and disillusionment.

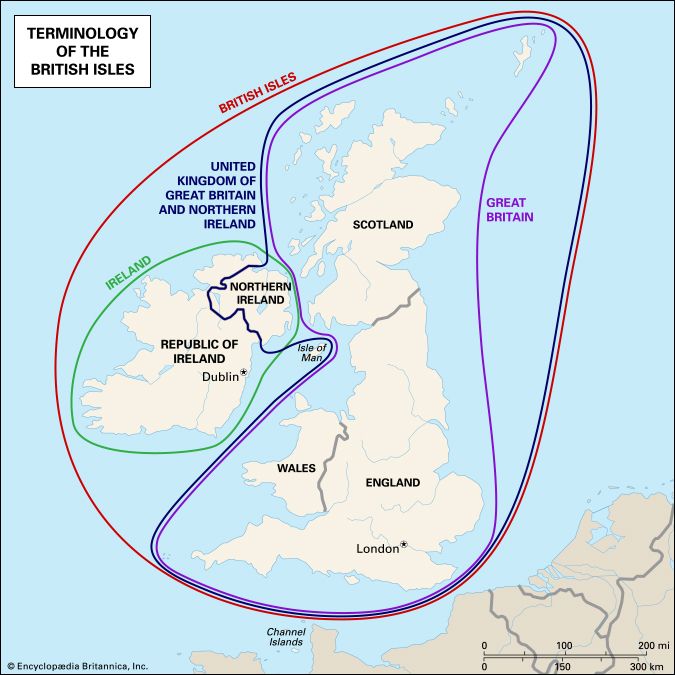

The main result of the Forty-five was the British government’s decision to integrate Scotland, and particularly the Scottish Highlands, more fully into the rest of the kingdom. Despite the Act of Union of 1707, clan chieftains had retained considerable judicial and military powers over their followers. But these powers were destroyed by the Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act of 1747. Other statutes required oaths of allegiance to the Hanoverian dynasty from the Episcopalian clergy, banned the wearing of kilts and tartans in an attempt to erode distinctive Highlands practices, and confiscated arms. The administration also confiscated the estates of Highlands chieftains who had rebelled and used the proceeds to encourage trade and agriculture in Scotland. Indeed, the gradual pacification of Scotland and its partial integration into a united Britain probably owed more to growing prosperity than to legal changes. By the mid-1750s Scotland’s population was estimated at 1,265,380, and it continued to grow at a rapid rate until the 1830s. Linen production doubled between 1750 and 1775, and coal mining, iron smelting, and agricultural productivity also began to expand. Economic and demographic growth was particularly dramatic in towns such as Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, and Dundee. The Act of Union had made Britain the largest free-trade area in Europe, and, as more Scots came to profit from trading and manufacturing links with England, more had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

The rule of the Pelhams

Defeating the rebellion also strengthened the position of the Pelhams. In February 1746, George II attempted to replace them with Granville but failed. Thereafter Henry Pelham and Newcastle insisted upon and received the king’s full confidence. The attempted invasion widened once again the gulf between the Whig and Tory parties. The Whigs became for a time more united, and the Tories did badly in the general election of 1747, winning only 110 seats. The only serious opposition Pelham faced after that date came from the heir to the throne, Frederick, prince of Wales. Although Frederick had abandoned the Opposition in 1742, his impatience to succeed to the throne soon prompted him to drift back into political intrigue against his father and his father’s ministers. He claimed to be motivated by some of Lord Bolingbroke’s political ideas. In 1738, during Frederick’s earlier phase of opposition, Bolingbroke had written The Idea of a Patriot King, arguing that a future ideal monarch could unify and purify the nation by seizing the initiative to abolish faction and ruling over an administration based on virtue rather than on party. Frederick’s avowed commitment to a nonparty government attracted Tory as well as a few Whig MPs to his support in the late 1740s. But their schemes and hopes were dashed when Frederick died in 1751. His eldest son, George (the future George III), became heir to the throne, and serious opposition to Pelham effectively ceased. Debate in Parliament became so muted, one politician wrote, that a bird might have built its nest in the Speaker’s wig and never be disturbed.

Both Pelham and Newcastle were overshadowed by their more famous predecessor Robert Walpole and by their charismatic successor, William Pitt the Elder. Like Walpole, both brothers regarded themselves as staunchly Whig though their ideology was by no means clear-cut. Like Walpole, they had little enthusiasm for British involvement in European wars. They helped to negotiate the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), which ended the War of the Austrian Succession. Like Walpole, too, the Pelhams sought to reduce the national debt and to keep taxation on land low. But unlike Walpole, they avoided corruption; both lost rather than made money during their political careers. And Henry Pelham was more interested in domestic reform than Walpole had been.

Domestic reforms

The Gin Act of 1751 was designed to reduce consumption of raw spirits, regarded by contemporaries as one of the main causes of crime in London. In 1752 Britain’s calendar was brought into conformity with that used in continental Europe. Throughout the continent, the calendar reformed in the 16th century by Pope Gregory XIII had gained widespread use by the mid-18th century and was 11 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which had been used in Britain. It was once believed that protests against this change—“give us back our 11 days,” crowds are supposed to have chanted—represented nothing more than parochial ignorance. In fact the adoption of the new calendar, though it ultimately benefited commerce and international relations, initially played havoc with monthly rental payments and wages in the short term. In 1753 the Marriage Act was passed to prevent secret marriages by unqualified clergymen. From then on, every bride and groom had to sign a marriage register or, if they were illiterate, make their mark upon it. This innovation has been of enormous value to historians, enabling them to establish how many Britons were able to write at this time and, by inference, how many could read.