The Freemasons have inspired centuries of conspiracy—this is their real history

The story of how a stonemasons’ guild became the world's largest secret society is less about conspiracy and more about Enlightenment thinking.

What do Rev. Jesse Jackson, George Washington, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Duke Ellington, and Buzz Aldrin have in common? All are members of the world’s largest secret society, the Freemasons—a group whose members include some of the world’s most influential people and whose secretive rituals have persisted for centuries.

Conspiracy theorists speculate the group pulls the strings of international power and finance and is responsible for high-profile murders—some even claim its members worship Satan.

Where is the line between fact and fiction within this secretive society? Read on to learn more.

The origins of Freemasonry

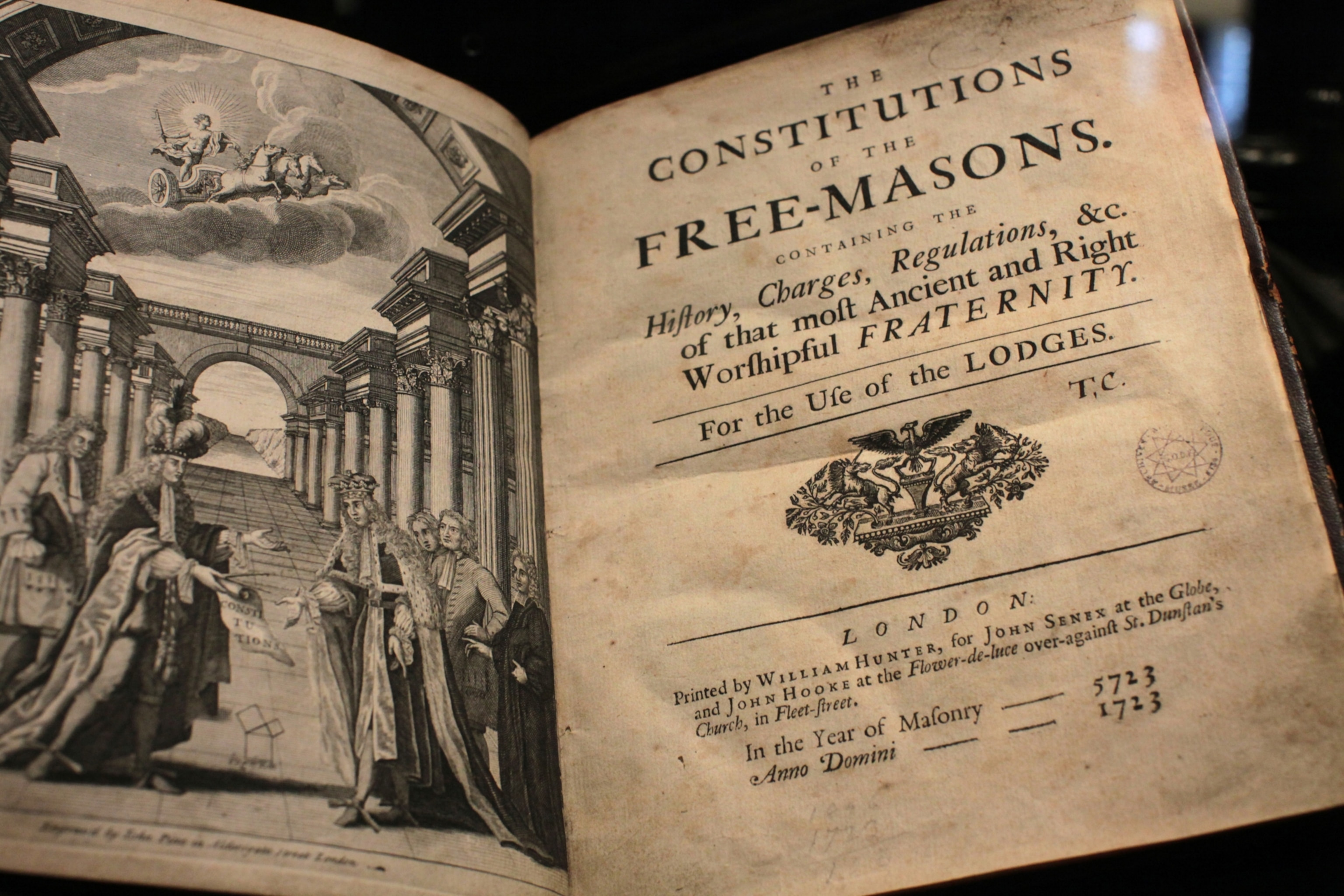

Though the Freemasonry movement has roots in medieval guilds of stonemasons, the vast majority of the movement’s members are not masters of stonework. It’s believed that as stonemason membership decreased, the group began accepting “speculative,” or honorary, members to bolster their numbers. Freemasonry’s modern incarnation dates to the 18th century Age of Enlightenment, when educated Englishmen aimed to commune with others and discuss issues of philosophy, religion, and life in an organized setting.

Fraternal organizations had existed for centuries, but in the 18th century, a variety of men’s groups named after the English pubs at which they met joined together in what they called a “Grand Lodge,” an association that would meet to hold rituals and ceremonies and induct new members. Now known as the Premier Grand Lodge of England, the group was the first of its kind, and as membership expanded so did its list of secret rituals and ceremonies and its membership requirements.

According to the Masonic Service Association of North America, there were about 898,000 Freemasons in the U.S. as of 2020, and there are an estimated 6 million Freemasons worldwide.

Who can be a Freemason?

Today, membership requirements are relatively simple: Though each group, or Lodge, of Freemasons has its own rules, in general a Freemason must be a male who is recommended by other members of the Lodge, believe in a “Supreme Being,” be of good moral character, and pledge to learn the ways of the fraternity and conform to what Freemasons call their “ancient uses and customs.”

Those customs include a strict hierarchy and a variety of ceremonies and rituals. After they are initiated into their lodge, members go through a series of “degrees” of membership, rising from Entered Apprentice to Fellowcraft to Master Mason. Along the way, they learn the language, rites, and beliefs of the “craft,” engaging in rituals that harken to Biblical beliefs . They also adopt emblems that range from the square and compass, which represents morality, the beehive, which is said to represent cooperation and work among members, and the “Eye of Providence” or “All-seeing Eye,” which represents God’s eternal watchfulness. Some of these symbols are so well known that they are familiar to non-Masons—for example, the Eye of Providence can be found on U.S. one dollar bills.

Why Catholicism forbids Freemasonry

When they’re not holding elaborate membership rituals, Freemasons often engage in community service and philanthropy, provide mutual support to members, or work with associated organizations. But despite this charitable focus and the fact that it is not a formal religion, Freemasonry isn’t universally accepted. In fact, Freemasonry is banned by Roman Catholicism, which forbids Catholics from joining and encourages them to associate with Catholic organizations like the Knights of Columbus instead.

“Their principles have always been considered undesirable by the doctrine of the Church and therefore membership in them remains forbidden,” the Church declared in 1983. “The faithful who enroll in Masonic associations are in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion.” As Catholic Herald’s Ed Condon explains, the Church opposes Freemasonry because of its secular focus and its role as a sanctuary for “those with heterodox ideas and agendas.”

Power and panic

Those agendas have long spurred controversy because of the political power wielded by some Freemasons. Though the rules of most lodges discourage members from discussing politics, many of its members are active in political parties and government and the organization’s secrecy and vows of brotherhood have spawned conspiracy theories about its members’ political agendas.

Most conspiracy theories speculate that all Freemasons have the same beliefs and act as a body, tying in with modern anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that associate the group with a shady “New World Order” which controls international finance and relations.

As a result, Freemasonry has become iconic in popular culture and among non-members who are intrigued by its shady rituals. Yet membership has dwindled for years. Why the decline? Some connect it to a larger trend among fraternal organizations and service clubs like the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, which have seen steep declines over the decades. Others attribute falling membership to the movement’s refusal to recognize women despite the existence of some all-female lodges.

Or perhaps the fall is due to growing public awareness of the movement’s once-secret rituals, historian John Dickie told NPR in 2020. “I think possibly actually the issue is that secrecy has lost something of its magic," Dickie said. “In an age when it can take two minutes or less on Google to find out what the Freemasons' secrets really are, I'm not sure that they can really hold that much mystique for members anymore.”

Despite controversy and condemnation, the movement persists—but only time can tell whether Freemasonry can remain relevant in the 21st century. Meanwhile, its members say they see Freemasonry as everything from a powerful brotherhood to a chance to give back to the community to what one English member calls “an avenue for personal growth and development.” For now, Freemasonry’s secretive rituals and symbols live on—along with the influence of its best-known members.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- 6 animals Nat Geo staff think are very demure, very mindful6 animals Nat Geo staff think are very demure, very mindful

- Why are cell phone contaminants showing up in tiger sharks?Why are cell phone contaminants showing up in tiger sharks?

- This parasite uses an army to suck out the guts of its enemiesThis parasite uses an army to suck out the guts of its enemies

- Why this rare salamander became a conservation iconWhy this rare salamander became a conservation icon

- How to keep your dog safe from toxic blue-green algaeHow to keep your dog safe from toxic blue-green algae

Environment

- Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

- Paid Content

Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer - This coral reef should be dead—so why is it thriving?This coral reef should be dead—so why is it thriving?

- Inside the Native Hawaiian push to rebuild Maui after wildfiresInside the Native Hawaiian push to rebuild Maui after wildfires

History & Culture

- The eighth wonder of the ancient world may have an untouched tombThe eighth wonder of the ancient world may have an untouched tomb

- These countries banned music—but artists still found a wayThese countries banned music—but artists still found a way

- A man’s world? Not according to biology or history.A man’s world? Not according to biology or history.

Science

- We've having a COVID summer surge—will winter be worse?We've having a COVID summer surge—will winter be worse?

- Home births are rising in the U.S.—especially for Black women. Here's why.Home births are rising in the U.S.—especially for Black women. Here's why.

- Why the traditional Okinawan diet is the recipe for a long lifeWhy the traditional Okinawan diet is the recipe for a long life

- We just learned where the asteroid that ended dinosaurs came fromWe just learned where the asteroid that ended dinosaurs came from

Travel

- How to plan a slow tour of the Valencia region in SpainHow to plan a slow tour of the Valencia region in Spain

- This Indian dish sparked a fierce lawsuit. Here's whyThis Indian dish sparked a fierce lawsuit. Here's why

- Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

- Paid Content

Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer