Wot I Think – Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

Can he do it? Shuriken

Sekiro hurts. It is a painful, graceful game about being a sword-swinging barbarian who must learn how to dance. Even more than its Dark Souls predecessors, it forces you to play on its terms: learn the steps or die. Fools sometimes say suffering leads to wisdom or insight. Well, you won’t gain enlightenment through the hundred deaths of this ninja follow-up. But you will learn how to do a lethal salsa. And when you finally stab your hairy dance partner in the eye, you will be awash in adrenaline. A deluge of battle endorphins that lasts long enough to enjoy after you’ve samba’d back to the rooftops to peer at the setting sun. For some of us, that's nirvana enough.

Warning: I’m going to crouch-walk around some spoilers, partly out of respect for you, our salivating horde of readers, but also so you can’t laugh at me for only reaching the [REDACTED] after 30 hours. However, plenty of small things will be spoiled.

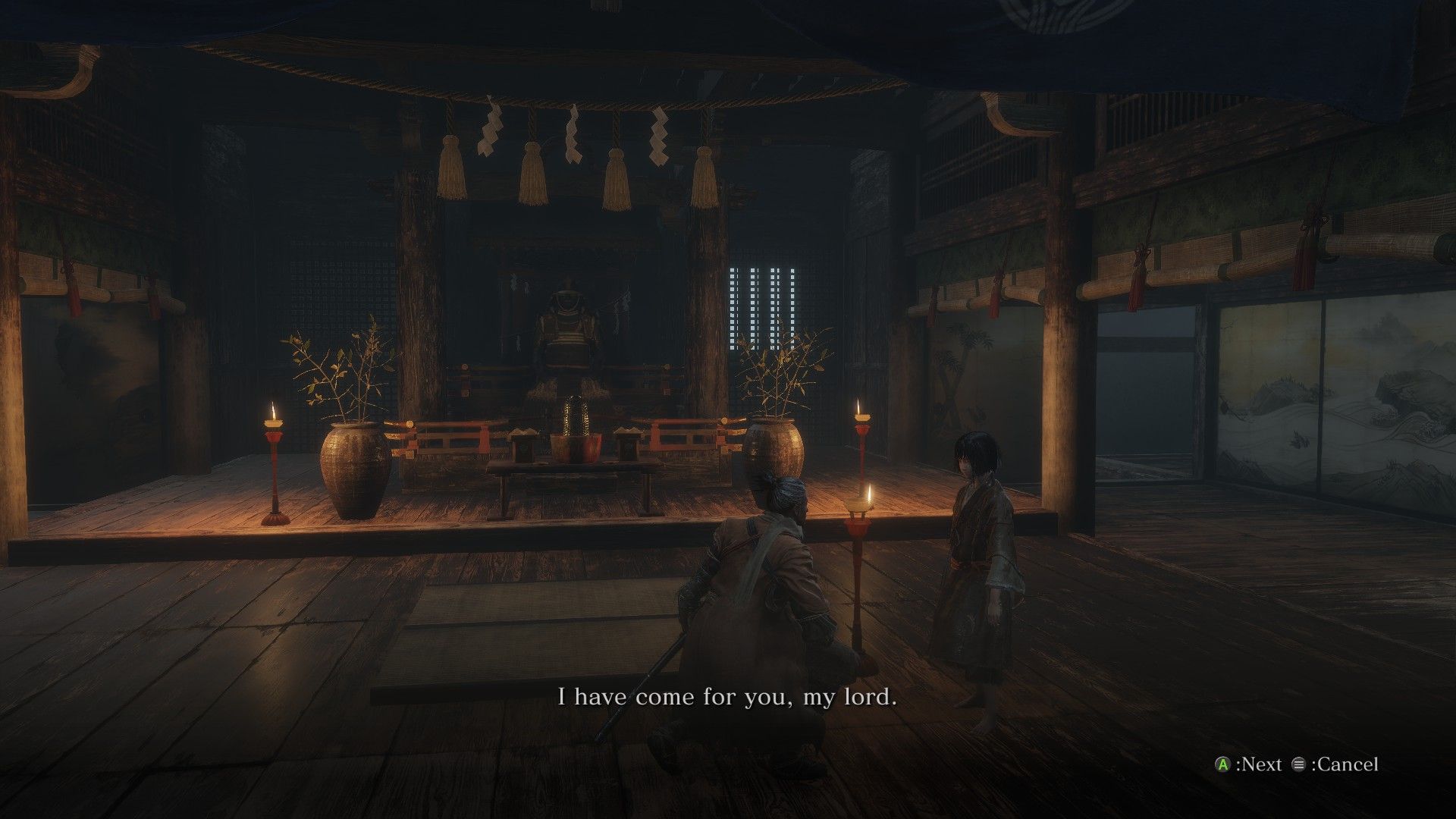

To explain your purpose in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, you are an unkillable assassin, told to protect your lord. He’s a wee lad called Kuro, who can make people immortal. Baddies love that, so they kidnap him. Off you go to the rescue, fighting brutes and swordsmen along the way. It’s like Dark Souls, but instead of impenetrable lore guff, there is a semblance of character and motive. But more on that later. The story is still not the reason most folk will come to Sengoku-period Japan. Most come to get bruised.

Fighting is mostly about using a katana to slice and parry. It is both shield and sword. In Dark Souls, a stamina meter would drain as you’re bashed, but here there is a “posture” meter. Both you and your opponent (let’s say a spear-wielding samurai lord) will have these posture meters. The aim is to fill that samurai jerk’s meter, at which point you can do a special stabby animation (a “deathblow”) that takes away all his health. Of course Spear Samurai is a mini-boss, so he has an instant refill of health. You have to deathblow him twice.

Beating warriors like him becomes an alarming jive. If you block precisely when a spear swing lands, you reduce his posture. This is a “deflection”, basically the parry from previous games. Chaining deflections is the goal of a good shinobi. But oh no. He also does swiping moves, thrust moves, and grabs. Each of these are countered in their own way. It's a fast-paced game of rock, paper, spear-in-the-groin. More intricacies trickle in to the combat, and the whole game carries on like one large lesson in mortal combat.

This can be overwhelming at first. In a boss fight, you’ll need to keep track not only of swords and powerful moves, but two health bars, two posture meters, any status effects, and incoming unblockable attacks. It’s deadly. Where mini-bosses are often accompanied by sidekick soldiers, thinning the crowd requires precise timing you may not have practised. But of course, in these games, death counts as practise. Working through early dejections eventually left me capable of felling whole groups of knifey fellas in a few elegant movements.

You can also dispatch foes stealthily, jumping on them from above or sneak-stabbing from behind. Yes, you can jump in this one, and hang from ledges, and grapple-hook to pre-ordained points. But often the spacing between ravenous samurai blokes is designed so you can only get one stealth kill. Because five other irritable swordsmen will immediately notice you killing their pal, and force you to fight like a brave person and not the hideous coward you are.

Other areas are set-up to be stealthed. One courtyard offers the chance to assassinate nine baddies in sequential silence, before backstabbing a spear-wielding mini-boss and then doing the mortal tango with him undistracted. I know there are exactly nine baddies because I killed them so many times I have a mental map of their positions scrawled in my skull. The tango is hard.

In fighting these nimble horror-warriors, you realise how blunt the axe-swinging of Dark Souls is. Smash and block, roll and gulp. In Sekiro, however, fights can quickly turn into tense rallies of deflection and counter-deflection, swipe and jump and slash and slide. Every swing of an enemy’s katana seems designed to test your nerve. Foes will feint, or delay their strikes with fearful suspense. It doesn’t want you to learn strength, or agility. It wants you to learn composure. To press the deflect button at precisely the right moment, then do it again ten more times. As much as it rewards you for killing these monsters, it values more readily the ability to stare them down.

Chatting in the RPS treehouse, Matthew said the best battles are like duels. And while lot of fights still have a scrappiness to them (leaping back and swigging from your gourd) that sense of two killers each trying to cut the other’s throat is unmistakeable. A hectic foxtrot, a bloody bolero. Oh no, you’ve been impaled. Your footing was off.

When you cut through mobs of soldier fodder, you’ll often do a “deathblow” for flair or efficiency. But this fatal blood-spattering animation becomes something else in boss fights. After minutes of clashing blades, vaulting over low swipes, and trying not to perish for the sixth time, the final deathblow in a boss fight comes as a superb moment of release. Is there something faintly sexual about panting through a 5-minute encounter with a spikey mancreature who looks like Voldo from Soul Calibur, and finally grunting with relief as all the tension flows out of you in one climactic spurt? No. No. It’s about stabbing. Please excuse me.

Anyway, it’s very good, and very difficult. I previously wrote that it seemed an easier game. What a foolish child I was. I see now that it is tougher, stricter. If you don’t keep slashing and deflecting, your foe’s posture will regenerate. If you don’t learn how to deflect strikes with frequency, you will struggle. And there is no multiplayer, so you can’t bring kind strangers to a fight for help. This is a classic raising of the ante by From Software, a studio locked in a perpetual arms race with its players. You blocked too much in Dark Souls, so they took away your shield. In Bloodborne, you recruited other players too much, so they took away your mate RichieOfAstora123. And in every game, you rolled or dashed too much, so they added “posture”. You can almost hear Miyazaki shouting through the code. “Stand still and fight, you coward!”

That arms race infects everything. So much of Sekiro is designed to fight the cheesiness and underhanded tactics that you, as a player, want to discover. Ah, you think, the rooftops are my new best bud because I can assassinate freely from up here. Well, replies Sekiro, let’s put some straw-hatted birdmen up there to throw shuriken at you as you leap. That’s fine, you think. That’s fine, I can unlock this skill that deflects projectiles in mid-air. Okay, says master Sekiro, I shall launch one of my birdmen at you from the sky.

It’s hard to get used to. I am a Soulser who often relies on the kindness of jolly co-operators to defeat my bosses. If that’s you too, you’ll sometimes find yourself helplessly wandering the castles and forests, with bosses in all directions, cornered by your own ineptitude. But From Software are not blameless geniuses. They are still fond of some infuriating practices. At least one mini-boss fight takes place in an uncomfortably small chamber, where the camera gets squashed against you every few seconds, obscuring everything. For those familiar with the Capra Demon, welcome back to the hell cupboard. A tough fight is a good fight. But when the game’s camera going screwy is baked into the difficulty of that fight, I call bullshit. It’s a rubbish tool to make something harder. Stop that.

There are other annoyances. Gargantuan nasties who seizure wildly in a way that is impossible to see coming. The "lock-on" to your target becoming unmoored because of camera shenanigans. Sometimes you will grab at a ledge that is comfortably within range, only to slide into the abyss. The game mercifully plucks you back up, but it also takes a big chunk of health from you.

At times I don’t know if it's encouraging me to do better with its harshness or if it is simply an abusive jerk. There have been many moments of struggle in which I thought: No, this is where I check out of the Souls games. This is where I get off the pain carousel. But then I’d return and slash a big animal on the bum until it died. That flood of fizzy brain chemicals would come back, a new land would open up to explore, and I’d remember why I adore these vast, gorgeous deathtraps.

There are ways in which it is more welcoming. Small but noticeable. There are arrow icons to show when an enemy can see you coming. They turn yellow when a scumbag is searching for you, red when one has spotted you. There are icons in front of doors to show you can open them, icons on grappling hook points. A blue icon appears when you’re close to a checkpoint altar, showing you exactly where it is. Sometimes a big pop-up window appears, simply telling you how to pull off a new move, moments before that move will be required in a boss fight. Imagine that. A Souls game, simply telling the player how to do something. How novel.

Some might say these are signs of the publisher’s influence, Activision’s shameful process of sanding down the edges of these obscurantist games. They might call it the capture and formalisation of a maverick studio who disregarded common practice, a diabolical bargain that trades mystery and originality for the blunt professionalism of tutorial pop-ups. Others might just say: “Thank fuck I can see the bonfires.”

You also have special weapons you can equip to your prosthetic arm (you got your arm cut off, by the way). There’s a big axe that shatters shields, fireworks to frighten beasts, a steel umbrella that protects against bullets. Violent and useful gadgets, whose usefulness is often telegraphed by eavesdropping on soldiers. Shortly after getting a spear that strips armour from foes, for example, you run into two skinny murderboys. “Well,” one of them says, “I’m glad we put armour on the big man in the next room, I hope it doesn’t fall off, ha ha.” You also have an elderly sculptor pal who can upgrade these prosthetic weapons. He’ll make your fireworks last longer, or your flame-gun blast hotter. Unlike the adaptable weaponry of Dark Souls, it feels like each prosthetic has its purpose, its moment.

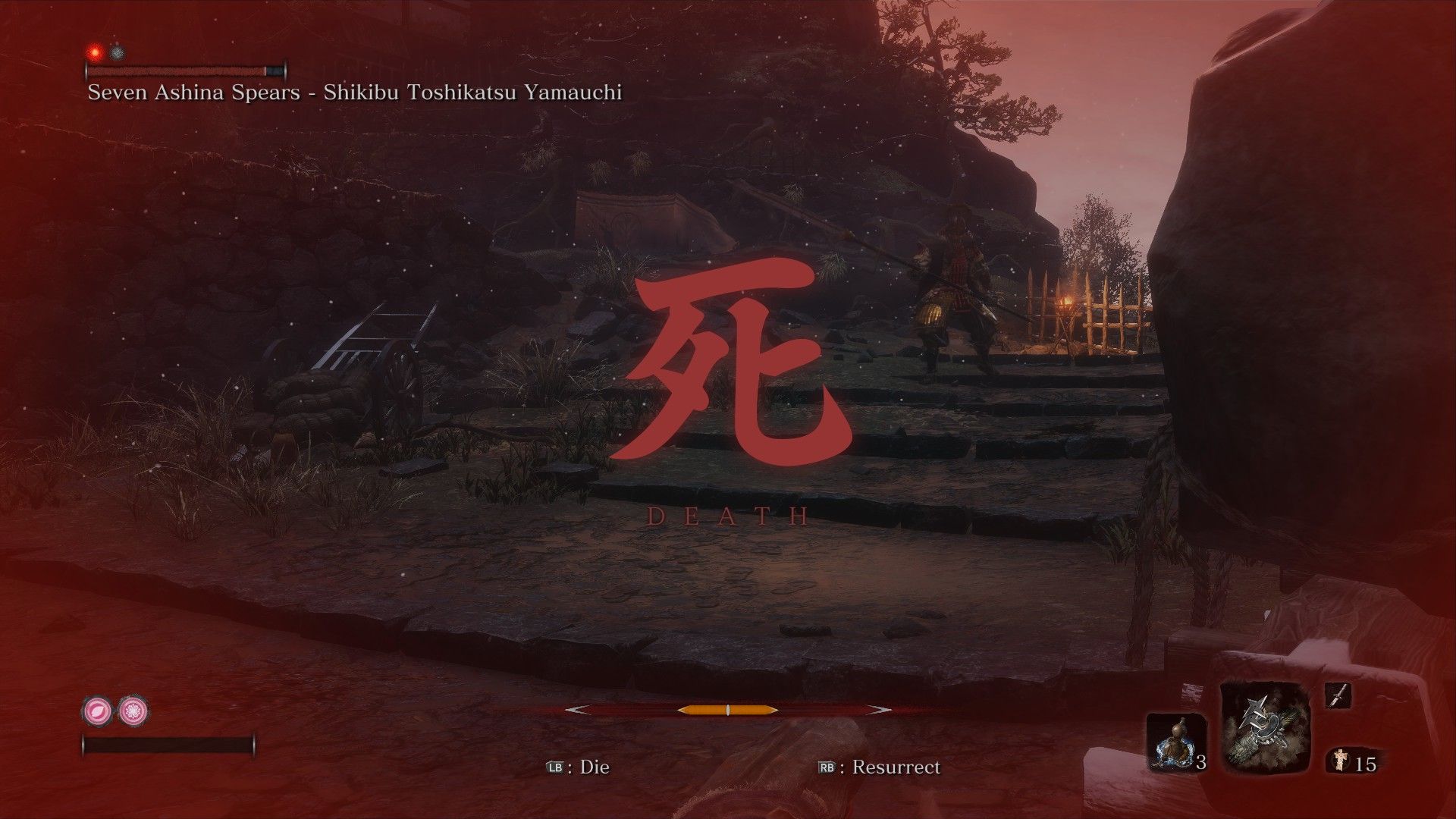

There’s the resurrection gimmick too. When you’re killed, you can rise up and get stabbing again. But if you’re killed shortly after this, you are proper dead. Dead-dead. You will lose half your skill points (think XP) and half your money (used to buy stuff from merchants). But if you dispatch your killer and murder more folk, you’ll recharge your resurrect ability. This is good when you’re killed by an unexpected trap. It soothes the unfairness of a demise you couldn’t have seen coming by giving you a chance to get up and dust yourself off. And when a lesser warrior lands a lucky blow and walks away from your corpse, you can sneakily get up and stab them in the back. It’s less useful in boss fights, where the wicked demons and brutes of feudal Japan like to stand over the bodies of their victims, pawing at their kill like a sad cat.

Mostly, it’s simply a way to have two lives, like Sonic with some rings. The game over screen, with its choice of “death” or “resurrect”, could also be more goading from a studio who loves to punish overconfidence. A jeering “go on mate, have another go” from the vicious programmers who brought you Blighttown. I prefer to look at it another way. It delivers a message: Hastily chasing victory will get you killed, whereas reflection, pause and calmness wins duels. Hammering the resurrect button and jumping back in to a fight often leads to shakey-handed disaster. But waiting for a beat and thinking for a few seconds offers the hope of a backstab, an escape, or a second chance. The wisest shinobi accepts the inevitability of death (and comes back later with a kickass upgrade).

I love this. Souls players have known for years that frustration, anger and eagerness only leads to more pain, as you “tilt” and become impatient and easily killed. But they’ve rarely had it said to them as overtly as this simple screen. With the posture meters Sekiro forces you to keep up pressure and be aggressive, lest your foe recover. With the death screen, it reminds you to breathe.

Breathing is important, and quiet moments are appreciative ones. Much of my Souls joy comes from walking into new lands and admiring the view. The landscape artists and monster sculptors of this studio have been turned loose on a folkloric feudal Japan, and it is splendid. It can’t replicate the twisting geographical intelligence of Lordran’s labyrinth (to me, no Souls follow-up ever has) but the snowy canyons and autumnal woodlands are more appealing to me than the oppressive brickwork of Yarnham and its Victoriana, or the by-the-numbers dungeoneering of Dark Souls 2. It also has a better tale. But, uh, marginally.

The Dark Souls trilogy had the twin crutches of mystery and obscurity to hobble on. For me, that was never convincing, but it meant hordes of Souls-lovers could forage in the lore gutter, slurping up item descriptions and piecing together unwieldy theories about dragons who love to read, or whatever. In Sekiro, the story is plainer, more direct. It still has that tinge of oddness. The sculptor can only carve wrathful Buddha figures, no matter how peaceful he tries to make them. Disproportionately sized animals roam the land. Buddhism is made grotesque with worm-infested monks in the same way Christianity was made repugnant with the priests and deacons of Dark Souls 3.

But it’s still not great storytelling. As ever, it relies more on style than the substance of its characters. Plot-wise, it is the most sensible a Soulsy game has been, and I like the wheezing, decrepit sculptor of your home temple as much as I like the bright-eyed Solaire of Dark Souls the first. Yet no character has the depth lacking in the protagonist. Without anyone to care about it remains a game about testing your might and killing bosses. I’m fine with that, given it says more interesting things with a death screen than with any line of dialogue.

With its more sensible story, helpful icons and tutorial pop-ups (not to mention the extra life), a bystander to the Souls games would be forgiven for thinking this is their chance to climb aboard the whirligig of agony. But newcomers shouldn’t be mistaken. This is still a game of grandiose self-flagellation. A murderous gauntlet of learning-by-death. And without the sunboys and sungirls of multiplayer co-op, it is the most difficult be-killed-em-up I have endured since my baptism by Asylum Demon.

But I won’t tell you to stay away. Look at these bruises, look at these scars. Yes, Sekiro hurts. But look at this smile as well. Shadows Die Twice is a beautiful, masochistic misadventure. Some of its boss fights are so stupendous, I dare not speak about them. It is a test of mettle and nerve that proves From Software are still winning the arms race against us cheesey rats. A brutal master who snaps the shield and broadsword out of your hands, and looks you up-and-down for what you are capable of. No more blocking, chump. You’re going to learn ballet.