The Ell Shop, Dunkeld: With an Ell Measure on the Outer Wall |

Scotland uses the same system of weights and measures as the rest of the United Kingdom. Or should that be "systems"? Because what the visitor encounters on a day-to-day basis across Scotland is a confusing mess in which old-style Imperial units are used for some things, and international SI units used for others, in a way that seems to completely defy logic and common sense. If it's any consolation, the situation in Scotland could have been far worse. Until UK legislation in 1824 brought them into line, many Scots weights and measures, although often having the same names as their English counterparts at the time, represented different amounts. And until Scottish legislation as recently as 1661, there was no standardisation even within Scotland.

So how can a visitor from Europe or the United States used to using a single set of units begin to make sense of things here? The only possible approach is to run through the most common types of measurements, giving a commentary on which units you are likely to find in use for each. We round off with a look at the historical picture before 1824, when Scottish units were different from sometimes identically named English ones.

Length. Large horizontal distances, for example between different towns, tend to be measured in miles, and road signs give distances in miles. But for shorter distances, things are more complicated. Most Scots under 40 were brought up with the SI system that would see them running a 100m race and generally thinking of distances of below about a mile in terms of metres. And for decades, nearly all our maps have carried a National Grid that is calibrated in metres. On the other hand, listen to people, especially the older generation, working out the size of a room or where to place furniture within it, and they'll probably be using feet and inches to measure distance: even though the furniture they are placing will invariably have been produced to standard SI sizes. Bring things down to still smaller scales, and you will still find older people talking of thousandths of an inch while their younger counterparts discuss decimals of a metre.

Speed. In part, this follows directly from the consideration of length. Speed limits are given in miles per hour, and car speedometers are primarily calibrated in miles per hour. An added complication here is the use in nautical and aviation circles of knots, or nautical miles per hour. 1 knot equals about 1.15 miles per hour or 1.75 kilometres per hour.

Height. This is nearly as confusing as length. Ask someone in the street in Scotland how tall they are, and if they are under 40 years old, they will probably give you an answer in centimetres; while if they are older they will probably tell you in feet and inches. Road signs warning of height barriers or low bridges usually give heights in metres. Increase the scale a little, and it is usual to express the height of hills and mountains, and points on hills and mountains, as metres above sea level. Except that many people will at the same time be mentally converting those figures to feet, even as they use them. Scotland is proud of its Munros, its mountains over 3,000 feet high, and it Corbetts, its mountains over 2,500 feet high: so while many in the mountains will be using an altimeter calibrated in metres, they will probably be thinking about the nearest equivalent thousand feet. And then, when you move the scale up further, aviation in the UK measures its height in feet, not metres.

Liquid measures. By law, most liquids have been sold by the litre in the UK for many years. Except beer purchased over the bar in pubs, which is sold in pints, and milk, which is sometimes sold in pints and sometimes in fractions of a litre. And although beer is sold in pubs in pints, wine and spirits sold in the same pubs are in measures calibrated in millilitres. If all this were not enough, although petrol is sold in litres, we calculate fuel consumption of our cars primarily in terms of miles-per-gallon.

Weight. Most foodstuffs have, by law, been sold in kilograms and grams for a very long time. However, many people still weigh themselves by stones and pounds. And at the other end of the scale, literally, there has long been deep confusion over the tonne (which, though not a formal SI unit equals 1,000kg) and the ton (the Imperial measure made up of 2,240 pounds weight or a little over 1,016kg) though it does help that the two are not very different. Tons are additionally confusing because they are often used in relation to ships: and there the term can mean a number of different things, ranging from the amount of water the ship displaces to its cargo carrying capacity.

Area. At the scale of a country, Scots tend to think in terms of square miles rather than km². Bring it down a little, and you are quite likely to find both hectares and acres used to describe areas of land. An acre is equal to about 4,046 square metres or a little over 0.4 hectares. Bring the scale down again, and you are quite likely to find both square feet and square metres in common use.

Conclusions. What is interesting is that while many of the "headline" Imperial units remain in everyday use, often alongside SI units, many of the less commonly-used units have faded away. In distance, rods, perches, chains are all pretty meaningless now, and a furlong means nothing outside the confines of horse racing. The areas where confusion reigns supreme are the areas where either an anomaly exists in the "formal" system, for example in the use of miles for distances, or where a concept is so deeply ingrained in people's minds that it could easily cross the generations. Measuring personal weight in stones and pounds is a good example of this. An example where this has not happened is in the measurement of temperature, where the age at which people think in "Centigrade" rather than "Fahrenheit" is steadily rising as the years go by, and it is quite easy to foresee a future in which no-one in the UK thinks in Fahrenheit.

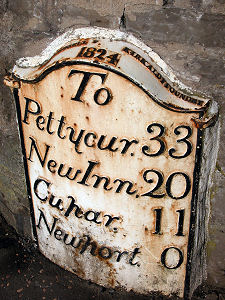

Old Scots Measures. Until 1824, a mile in Scotland was defined as the length of Edinburgh's Royal Mile, and was subdivided into 320 falls, each of 18 Scots feet. This made the Scots mile about 10% longer than the English mile that has since replaced it. And although in 1661 the Scottish Parliament tried to standardise measurements within Scotland, for some time afterwards a "Scots Mile" could mean any of a number of different distances. Another lost Scottish measure was the ell, which equated to 37 Scots inches. This was particularly used to measure lengths of textiles and continues to have a resonance in the "standard" ells sometimes found inscribed into the bases or sides of market crosses, and in at least one case marked on the outside of a shop.

We could go on to talk about bolls, firlots and pecks, all measures of dry volume; or gills, mutchkins, chopins, jougs (or Scots pints) and Scots gallons, all liquid measures. Because you're probably wondering, a mutchkin was equivalent to 424 millilitres, or half a chopin. Four chopins made up a joug, and eight jougs or Scots pints made up a Scots gallon. In many ways the names that were different from the English measures are less misleading than those that seem the same. The Scots pint and the Scots gallon were both around three times the volume of their English equivalents.