Craig Mazin did not expect Chernobyl to become one of this year’s buzziest TV dramas. A historical tale about the aftermath of the 1986 Soviet nuclear explosion, the HBO miniseries derives its drama from bureaucratic malfeasance and features oozing wounds and some of the most drab decor seen on TV since the actual ’80s. Mazin laughs at the memory of pitching a show that, as he puts it, “begins with a hanging, will not have any romance or sex, and is about science and history!”

It’s not like Mazin had a reputation for making gritty, realistic drama; he’s best known for his screen writing on the Hangover sequels. But on Chernobyl, he intentionally avoided easy resolutions or concessions to sentimentality. In the real world, the central figure in the story—Valery Legasov—had a wife and family. But the nuclear physicist played by Emmy-nominated Jared Harris does not. The golden rule of the production, Mazin says, was to always “go for the less dramatic, less sensational version.” That meant no scenes of kids whimpering, “Please don’t do it. Please don’t go!”

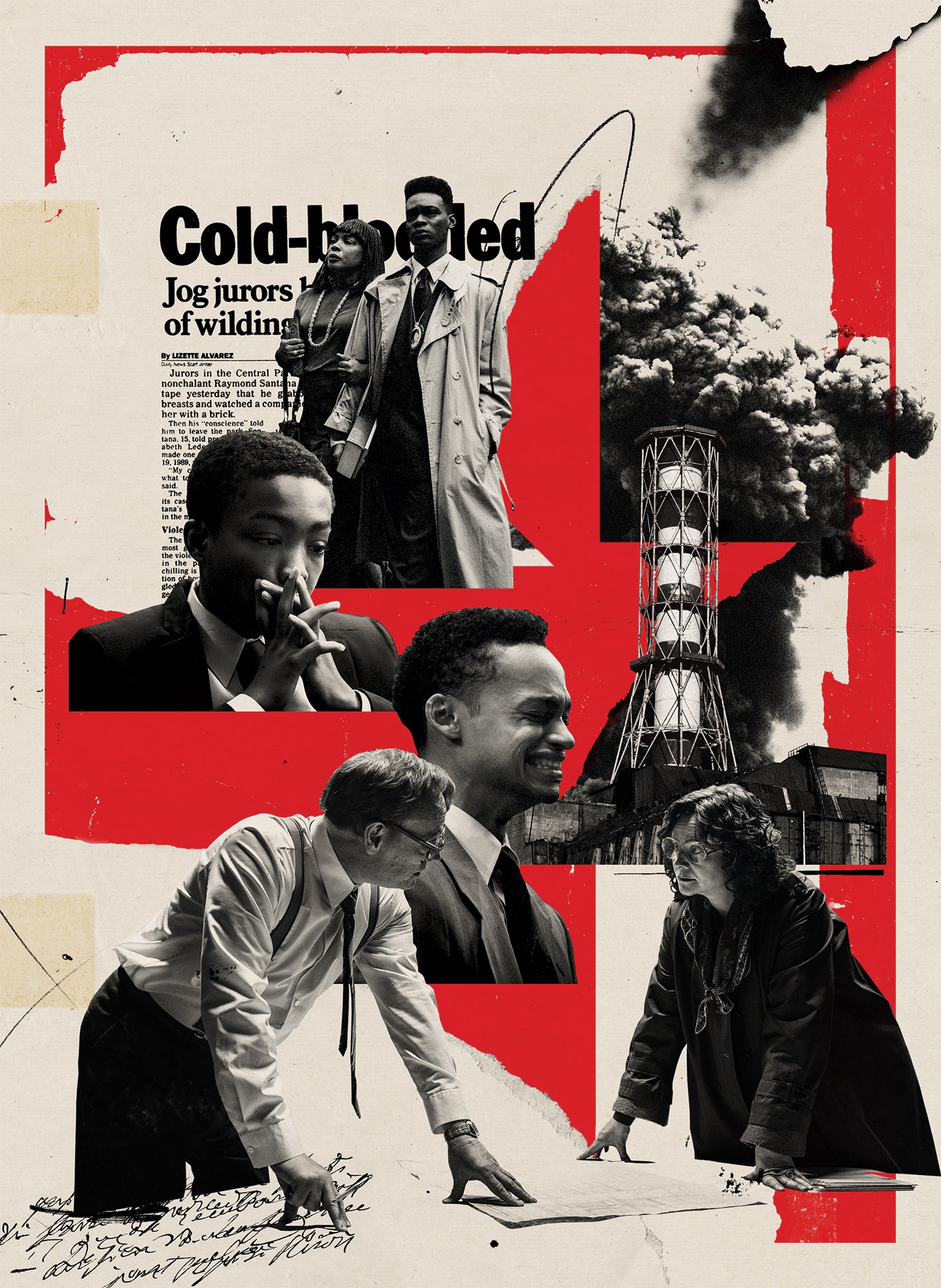

Ava DuVernay took similar care with When They See Us, her devastating four-part Netflix series about the five East Harlem teens unjustly accused of raping a jogger in Central Park in 1989. Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Kevin Richardson spent years in juvenile facilities; Korey Wise, who, at 16, was older than the others, spent more than a decade in adult prisons. All five were exonerated in 2002. Although the case had been written about extensively at the time, the men felt the story needed to be viewed from their perspective. “There was so much more to it, and I wanted to tell it for them,” DuVernay told VANITY FAIR this spring. She chose a title for the series that sidestepped their previous tabloid moniker, the Central Park Five, instead emphasizing the boys’ need to be humanized and “seen.”

HBO says that up to 12.2 million American viewers have watched Chernobyl on its various platforms since the miniseries began airing in May. It earned 19 Emmy nominations, including for outstanding limited series. Meanwhile, When They See Us landed 16 Emmy nods and—while Netflix’s internal numbers are impossible to verify—has been watched by more than 23 million accounts around the world, according to DuVernay, who tweeted, “Imagine believing the world doesn’t care about real stories of black people.” Those are staggering numbers amid the superhero and fantasy franchises that dominate contemporary pop culture, inviting us to exit our dismal reality for a few hours of glittery escape. The success of Chernobyl and When They See Us suggests that there is a serious appetite for seriousness out there—and a surprising willingness to bear witness to such epic, real-life tragedies.

So where did this burgeoning genre—call it Must-Endure TV—come from? DuVernay and Mazin both grew up in an era when historical miniseries such as Roots and Holocaust were major cultural events that pulled Americans into mass seminars on our darkest historic crimes. But many in the industry cite American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, Ryan Murphy’s 2016 FX true-crime drama, as the flash point of our most recent iteration. With The People v. O.J. Simpson, followed by The Assassination of Gianni Versace, Murphy injected the history genre with a heady dose of true-crime gaudiness, resulting in a perfectly calibrated blend of the sober and the salacious.

There’s also HBO’s role as reliable purveyor of nonfiction-based scripted miniseries, from 2001’s Band of Brothers to 2015’s Show Me a Hero, as well as political movies like Game Change and Confirmation. Its latest limited series, Our Boys, premiering in August, is based on real events surrounding the 2014 abduction and murder of three Jewish teens in the West Bank, which spiraled into war in Gaza. The network’s commitment to such awards-friendly reenactments only burnishes its high-end brand. As the streaming race heats up, some competitors are finding that they are a good way to stand out in the ever more crowded marketplace. Among the recent examples are Hulu with The Looming Tower, Showtime’s Roger Ailes drama, The Loudest Voice (based on the reporting of VANITY FAIR special correspondent Gabe Sherman), and Netflix’s forthcoming limited series Unbelievable, based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning ProPublica article “An Unbelievable Story of Rape.”

When Murphy sketched out American Crime Story, FX boss John Landgraf instantly grasped the appeal of reappraising events embedded in America’s collective consciousness. “You have the opportunity to build a deeper emotional and historical context that allows you to penetrate the surface of the story,” Landgraf told me. FX’s next foray into history, the limited series Mrs. America, will zoom in on the ferocious battle around the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s. Cate Blanchett stars as Phyllis Schlafly, the anti-feminist activist who ultimately derails the campaign’s momentum. To Landgraf the moment has a “direct bearing on the political climate in which we find ourselves today.”

With historical dramas, Landgraf says his goal is to find “the overlap in the Venn diagram between what audiences will enjoy watching and what has genuine artistic or humanitarian merit. It’s a wonderful thing when any creator, any broadcaster can sort of find that place where it’s not homework to watch something, yet it has an enormous amount of artistic or educational value.”

The recent documentary boom and the popularity of high-end true-crime series have also smoothed the way for this historical-drama trend, alerting Hollywood to the pull of real-life stories told well. One industry insider told me that in the wake of Netflix’s Making a Murderer and HBO’s The Jinx, the industry had an “oh my God” moment regarding real-life stories—even better if those stories have a pre-primed audience.

“The biggest issue that faces us right now is not getting shows made but getting people to pay attention to them,” the insider says.

“The majority of our members watched at least one documentary in the past year,” says Cindy Holland, vice president of original content at Netflix. “So we know they’re really drawn to true stories.” Holland felt confident that viewers who binged on Making a Murderer or viewed 13th (DuVernay’s documentary about America’s prison system) could be lured into watching dramatized tales of injustice. Although When They See Us is an emotionally battering experience, Holland says, “you empathize or sympathize with these characters and you can’t turn away from those faces.”

Susannah Grant, who wrote Erin Brockovich and Confirmation, recently collaborated with executive producer Sarah Timberman on Unbelievable, revolving around the true story of Marie, an 18-year-old (played by Kaitlyn Dever) charged with lying about being raped.

“There’s such hunger for stuff that will address issues of national, international importance with a really good, compelling, dramatic take,” says Timberman. The series follows the two female detectives (Toni Collette and Merritt Wever) who unraveled the case, adding a slightly more upbeat note of strength and resilience. “Nobody wants to watch anything 100 percent devastating,” says Grant.

The project began before #MeToo went mainstream, but the story seems freighted with even deeper resonance in its aftermath. Bringing it to Netflix required enormous sensitivity—both onscreen and behind the scenes. “You want to be respectful of the lives that your characters are inspired by, of course,” Grant says. “But also, [on set] it’s just been really important to us to be really mindful because it’s very charged stuff.” During the shooting of one particularly difficult scene, she recalls, one of the women on her team dissolved in tears, confessing, “I underestimated how this would affect me. I’ve been in this bad situation.”

True-life dramas have to strike a delicate balance between historical reality and narrative form. Details sometimes need to be reshaped to make them TV-friendly; multiple people may be condensed into a single character for the purposes of dramatic efficiency. Michael Starburry faced these kinds of challenges when he cowrote the finale of When They See Us. The episode focuses on Wise (Emmy-nominated Jharrel Jerome) and his nearly 14-year journey through the adult prison system. We glimpse Wise’s terror and despair, as well as the violence he experienced at the hands of inmates. Starburry knew he had to stay true to “the spirit of the story” while ensuring that viewers digested it. “Some of the things that happened to Korey we did not write out of respect for Korey,” he says somberly. “Some of those moments…they’re not for mass consumption.”

Squeezing Wise’s ordeal into less than 90 minutes of screen time required the writers to make tricky consolidations. For instance, the kind prison guard named Roberts (Logan Marshall-Green), who gives Wise magazines in solitary confinement, is a composite character. “One of my favorite moments in that episode is when [Roberts] talks about how he has a son himself and he would just want to know that if the son was in that situation he was being treated like a human being,” Starburry says. He wanted to remind the audience: “[Korey] is someone’s kid.”

While audiences seem to understand that there’s necessarily an accuracy gap between factual documentary and dramatized TV, it has led some to become amateur researchers. I was one of many viewers who took to Google to read more about Central Park Five prosecutor Linda Fairstein—who was dropped by her book publisher in the aftermath of When They See Us—and to find details of the Chernobyl nuclear-plant meltdown, since the events in the series often seemed too outlandish to be real. Did cleanup squad members really have just 90 seconds each to rush out onto the nuclear plant’s rooftop and shovel chunks of radioactive graphite over the edge? (They did.)

“What attracted me in the first place were the facts,” Mazin says. “The decisions people made for better or for worse, the sacrifices people made for better or for worse…I built the story around the facts, I didn’t try and shove facts into a story I preferred to tell.” Mazin had a small team of people helping him fact-check the series. Later, HBO had its own researcher dig through the scripts for legal reasons—a bracing wake-up call. “You have to really justify everything you’re doing,” Mazin says. “And we did. In the end, I came to really love that part, because as the kids say, ‘I had the receipts.’ ”

Chernobyl hinges on the lies that the Soviet government told to downplay the immense damage to the nearby population and environment, as well as the very real risk of global consequences, in order to preserve the USSR’s image as a superpower. When a narrative’s central subject is the importance of truth, that puts extra pressure on its writers. Just how far can you stray from how things went down for the sake of dramatic impact? Mazin decided the solution was transparency: He recorded an accompanying podcast revealing details behind the fictionalized version onscreen and making more explicit connections between what happened in 1986 and our current political moment, with its “fake news” hysteria and looming climate change apocalypse.

Mazin thinks that in recent years, people have become aware that there’s a steep price for not paying attention. “Of all the many commendable things about Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, one of the most commendable is the title,” he says. “There’s something about being seen, and particularly, looking at people and events that otherwise you wouldn’t have looked at.”

It’s probably no coincidence that many of the historical reappraisals currently in the pipeline hinge on people of color, women, or LGBTQ+ characters—those shoved to the margins of history books and, too often, television as well. “I think there’s been much more interest in more underrepresented audiences,” says Netflix’s Holland. Upcoming examples include AMC’s horror series The Terror: Infamy, which is fictional but is set in America’s Japanese American internment camps during World War II, and The Infiltrators, a scripted series about undocumented immigrants that Blumhouse Television is developing based on a documentary of the same name.

Still, as Mazin points out, “Not all history is created equal. Some things have happened in history that were remarkable for their impact in the moment. Other things happened that maybe were passed over in the moment and only now do we realize how important they were.” He believes there are urgent lessons to be learned from an incident like Chernobyl: “We are living in the moment before the button gets pressed and the reactor explodes. The question is, will we do what needs to be done so that it doesn’t explode?”

— How intimacy coordinators are changing Hollywood sex scenes

— The Crown’s Helena Bonham Carter on her “scary” encounter with Princess Margaret

— The Trump-baiting Anthony Scaramucci interview that roiled the president

— What happens when you try to be the next Game of Thrones

— Why are teens flocking to Jake Gyllenhaal’s Broadway show?

— From the Archive: Keanu Reeves, young and restless

Looking for more? Sign up for our daily Hollywood newsletter and never miss a story.