The Japanese myths and woodblock art behind Sekiro’s creatures

Big fish tales

Fantastic creatures are as important to Sekiro as its samurai and shinobi. For every deftly fought duel against a venerable warrior there’s a slug-fest with a headless ape that hurls toxic poo. It’s a fine balance between the real and the romantic. Whereas Dark Souls had everything to do with “lore”, Sekiro more delicately pulls from folklore. Lordran is almost purely imaginative, but Sekiro’s Ashina is set securely in Japan during the Sengoku period, and closely draws from surrounding legends and myths.

Almost all its creatures are a play on yōkai, for example, a diverse group of strange, supernatural creatures. Many can be traced back to ancient tales, but it was the natural history encyclopedias and bestiaries of the Edo period that helped popularise them (most famous is Sekien Toriyama’s The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons, which catalogs over two hundred of them). Ever since, Japanese art and literature has built upon this legacy of monsters, demons, gods and animal spirits, especially in Japanese woodblock printing. It’s a rich artistic tradition, and its influence on Sekiro is clear.

Tengu

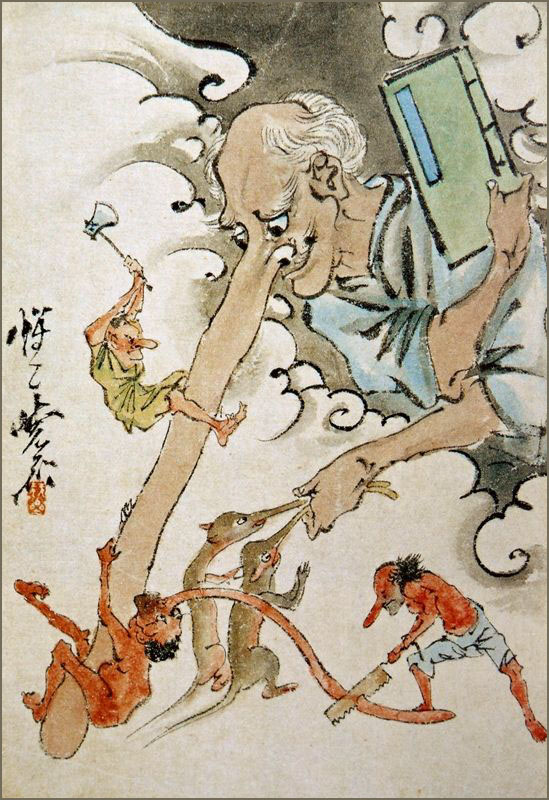

Let's start small. Tengu of Ashina is a key character whose name comes from the red, long-nosed mask he wears. Powerful, god-like demons, tengu are thought to be based upon birds of prey. Over time the creature’s depiction became less avian and more human. Its long beak becoming the extended (I’m obliged to mention phallic) nose we see today.

Tengu are said to be excellent martial artists, with Sekiro’s imposing warrior possessing two out of five of the game’s so-called “Esoteric Texts”, which teach our shinobi a range of combat abilities. The creatures are also held by Buddhists to be harbingers of war, which is more than a little relevant to Sekiro once you discover Tengu’s true identity.

Demon of Hatred

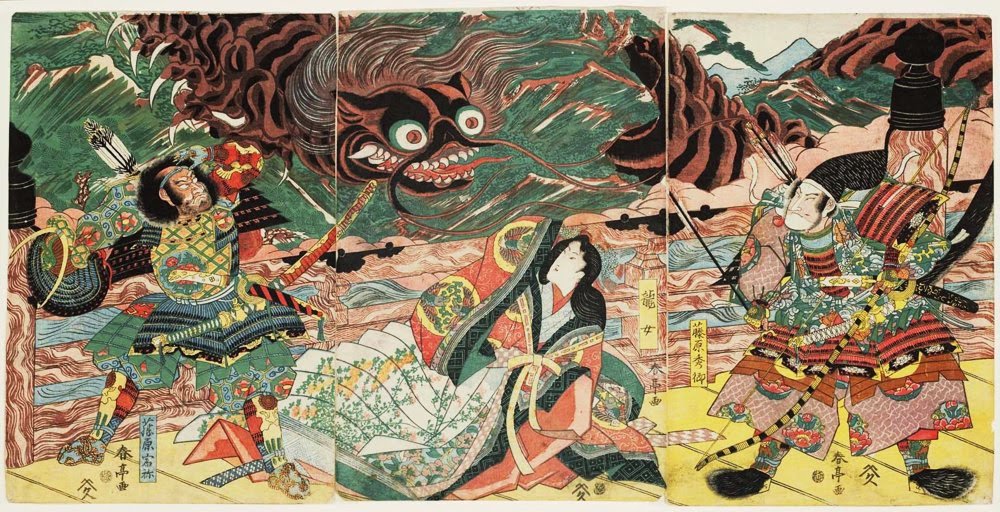

Along with the Chained Ogre boss, the end-game Demon of Hatred is based on the oni. These large ferocious demons are infamous in Japanese folklore, are never good news, and are often blamed for bringing all kinds of calamity. Captains of the underworld, oni are rumoured to be born from wicked humans whose souls are beyond redemption.

Sekiro’s Demon of Hatred certainly retains many of these elements, and while it resembles several other creatures from previous From Software games such as Manus and the Demon Cleric, it also bears a striking resemblance to oni depicted in Edo-era woodblock art. Fiery, horny (not that kind), with more than a little hair.

Divine Dragon

Neither a sword-fight nor a brawl, the Divine Dragon is the game’s most unusual boss fight. It’s also the most expected appearance in a myth-infused Japan. The long, serpent-like dragon can be traced back thousands of years to China. One of four auspicious guardians or gods (along with a phoenix, tiger and turtle). Sekiro’s Divine Dragon is not only said to have travelled to Japan from the West, but also has a clear association with Spring through its connection to cherry blossom and Sakura. There’s even a theory that the Dragon is the Everblossom - a fictional tree that’s always in bloom, and therefore immortal.

Dragons are also associated with the element of water (unlike its western counterpart which breathes fire). So it makes sense the Divine Dragon is found at the top of the flooded Fountainhead Palace area, and is the source of the rejuvenating waters which trickle down from its heavenly perch. As is so often the case with From Software’s work, the traditional dragon, powerful and divine, is subverted and shown to be both sick and corrupt.

Centipedes

Sekiro’s centipedes are the result of the Divine Dragon’s immortality-granting waters (why can eternal life never be straight forward?) These monstrous centipedes have a basis in real-life: the mukade, or giant poisonous centipede, which is native to Japan. There are, like all mythical bugs, plenty of tales about supersized variants. Whilst the real centipedes grow to a maximum of twenty centimeters, their mythical yōkai counterparts known as ōmukade are said to be able to grow to titanic proportions, with elder variants coiling themselves around mountain ranges and scaring off even the dragons.

Real life mukades are sturdy fellows, whilst the exoskeleton of the fictional ōmukade is entirely impenetrable unless the blade is coated in saliva. It therefore makes a lot of sense that in Sekiro these horrifying creepy-crawlies are both a latent poisonous force, and invulnerable to attacks until you possess the Mortal Blade. It’s just a shame you can’t bypass all the magical sword stuff and buff your regular old katana with spit.

Long-arm Centipede

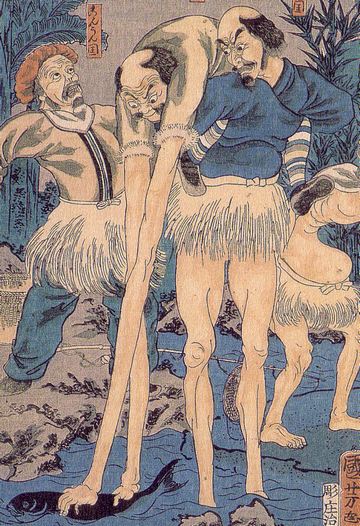

Sekiro’s oddly named Long-arm Centipedes come as a pair and look nothing like a centipede. Instead, their dangly limbs and erratic movements evoke the same kind of BDSM-energy as Soulcalibur’s Voldo. One of the creatures is called "Sen’un", while the other is called, uh, "Giraffe". I wish there was more to this story, like some link to a long-necked demon that whips you to death with its muscular throat, but Giraffe most likely stems from a mistranslation.

To make up for the disappointing lack of “giraffes” in the woodblock art record, I’ve instead found another peculiar yōkai-duo with long-arms. As a bonus it even has long legs. Ashinaga-tenaga are two separate entities that, when combined, make the world’s ultimate fisher. Ashinaga, the long-legged one, wades into deep water, whilst Tenaga plucks up the fish with its lanky arms. After reading every item description in Sekiro, and learning nothing, I’ve come to this speculatory conclusion: at some point these long-limbed friends fell out, split up and decided to live out the rest of their lives in pots, selling washed-up junk they found for the fish they were no longer good enough to catch. None of this has anything to do with centipedes or giraffes, but there you go.

Sculptor aka Orangutan

It’s clear that the Demon of Hatred is the tormented Sculptor who helps you by upgrading your prosthetic arm. He is also known as Sekijo, or “one-armed Orangutan”. While the mystery of the Demon’s origin has been solved, we can only speculate about the source of the Sculptor’s primate nickname. He explains that he trained as a shinobi amongst the macaques of the sunken valley, but the more likely explanation for his nickname is his appearance and personality. In his younger days the Sculptor might have resembled a yōkai known as a shōjō. These humanoid creatures possess long shaggy red hair, like orangutans, and are famous for their love of alcohol.

Likewise, the Sculptor is hairy and fond of sake and monkey booze (fruit stashed in trees by the macaques and left to ferment). Finding alcoholic drinks and gifting them to characters is often how we learn their backstories in Sekiro. The Sculptor is particularly cagey about his past, but fill him with enough drink and he opens up like a loaded umbrella. He’s fond of the hard stuff, and shōjō is a term often used in Japan to refer to heavy drinkers. After a hard day of carving Buddhas, it’s necessary to wet one's bone whistle.

Great Serpent

In Japanese mythology serpents are related to dragons, and therefore possess minor divinity. Sekiro’s two Great Serpents certainly seem to be worshipped, with the second of the pair guarding a shrine in which a serpentine fruit sits (the heart of a Great Serpent which you later feed to a child - don’t ask).

Along with the other serpent that hunts in the valley, the giant snakes resemble the yōkai Uwabami, who represents the cycle of life and eternal youth (two of the game’s key themes, in case you hadn't noticed). The Serpents are a symbol of immortality in a similar way to the Divine Dragon, and we see this in the game with their ability to shed skin and leave it draped on cliffsides and snagged on trees.

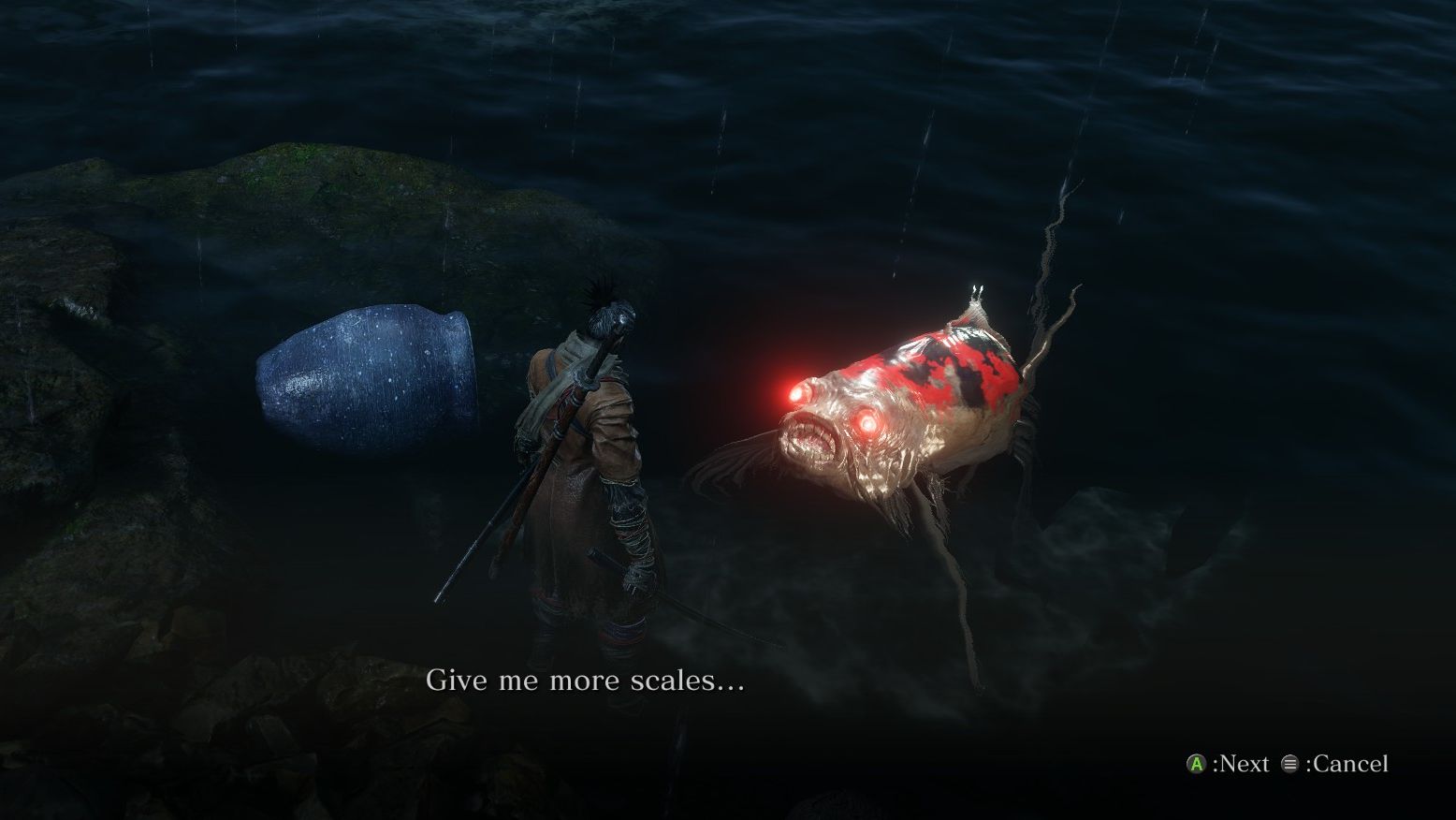

Great Carp

Carp or koi are a symbol of prosperity and good fortune in Japan. Their golden scales can be used as currency in the game to buy items from those strange men living in urns. If you shop with the pot-men enough, they’ll tell you all about the Great Carp residing in Fountainhead Palace and ask you to eliminate it so that one of them can reincarnate to take its place. Perhaps hoping to return to the watery depths which they once dominated, the great pot feud is the culmination of all of Sekiro’s biggest ideas. The tragedy of two long-limbed friends who became enemies, the downfall of the ultimate fisher, and the rebirth that finally settled the score.

Ahem. Putting the epic tale of the pot-boys to one side, giant fish are no strangers to Japanese myth. Namazu is a giant catfish whose thrashes are said to cause earthquakes. There are also the legendary stories of the warrior-monk Benkei, a half-oni who’s said to have won two hundred duels in a single battle and confiscated 999 swords from the samurai he defeated over his lifetime. He must’ve been gutted he never obtained that last katana. Benkei is a popular figure to adapt, and shows up in everything from Kabuki plays to film, manga and anime. In one of his most referenced adventures, Benkei wrestles with a giant koi much like our shinobi-hero does with the Great Carp.